The celebration of the Holy Eucharist, most often referred to as the Mass, is a liturgy that is celebrated every day in the Catholic Church. In most parishes that have more than one priest, it may be celebrated by each priest, so there are several Masses per day. While in locations without a resident priest, it may only be celebrated once a week or perhaps even less frequently.

However, no matter how often or how infrequently the Mass is celebrated it is the primary liturgy of the Church. It is a re-enactment of the event in which Jesus, at the Passover meal on the night before he died, took bread, blessed it and told his disciples to eat it because it was his body. He did the same thing with a cup of wine, blessing it and giving it to them to drink with the announcement that this was his blood.

Each day the Church offers the same Body and Blood, this Holy Eucharist, to God. However, there are two days of the liturgical year in which the Church focuses on this Holy Eucharist in a special way.

The first of these days occurs during Holy Week, the week before the feast of Easter. Indeed, it is the Mass of Holy Thursday that begins the days of special liturgies known as the Paschal Triduum. On Holy Thursday the last free actions of Jesus are ritually re-enacted: feet are washed, the Eucharist is offered, the consecrated Hosts are processed through the church and carefully stored (for there is no Mass anywhere on Good Friday) and the altar is stripped, reminding us that at the end of the evening Jesus was betrayed and taken prisoner.

The other feast, known as Corpus Christi or the Body and Blood of Christ was established as a feast of the universal Church in 1264. The focus of the feast is the Body and Blood of Christ as a mystery that stands at the heart of the Church.

These two feasts have different shades of meaning. On the one hand is the historic event that every Mass re-enacts. On the other is a meditation on the meaning of the event and of the mystery of bread become Body and wine become Blood.

Eucharistic iconography is a very complex subject, but I will only look at one type of these images today. This is the distinction between images depicting the Last Supper and those depicting the Institution of the Eucharist. At first glance this may seem confusing. After all, aren’t they the same thing? Well, yes and no. Although the events depicted are essentially the same, the manner in which they are depicted is different.

Both types of painting focus on the events in the Upper Room on the night before Jesus died. As the Gospel of Matthew (and the other Synoptic Gospels) tell us:

"While they were eating, Jesus took bread, said the blessing, broke it, and giving it to his disciples said, "Take and eat; this is my body."

Then he took a cup, gave thanks, and gave it to them, saying, "Drink from it, all of you,

For this is my blood of the covenant, which will be shed on behalf of many for the forgiveness of sins."

(Matthew 26:26-28)

Both types of images are set in the Upper Room, both usually feature a table. Apart from that they are very different in the figural composition and narrative content.

Eucharistic iconography is a very complex subject, but I will only look at one type of these images today. This is the distinction between images depicting the Last Supper and those depicting the Institution of the Eucharist. At first glance this may seem confusing. After all, aren’t they the same thing? Well, yes and no. Although the events depicted are essentially the same, the manner in which they are depicted is different.

Both types of painting focus on the events in the Upper Room on the night before Jesus died. As the Gospel of Matthew (and the other Synoptic Gospels) tell us:

"While they were eating, Jesus took bread, said the blessing, broke it, and giving it to his disciples said, "Take and eat; this is my body."

Then he took a cup, gave thanks, and gave it to them, saying, "Drink from it, all of you,

For this is my blood of the covenant, which will be shed on behalf of many for the forgiveness of sins."

(Matthew 26:26-28)

Both types of images are set in the Upper Room, both usually feature a table. Apart from that they are very different in the figural composition and narrative content.

The Last Supper Images

Images of the Last Supper present Jesus and the Apostles seated around or on one side of a table and engaged in a meal. Classic examples are the well-known images by Giotto, Duccio and Leonardo da Vinci. Jesus may be seen to be blessing the bread or not. It is the moment just before or just as Jesus pronounces the words given in the Gospels.

|

Giotto, The Last Supper Italian, c. 1304-1308 Padua, Scrovegni/Arena Chapel |

|

| Giotto, The Last Supper Italian, c. 1320-1325 Munich, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Alte Pinakothek |

|

Leonardo da Vinci, The Last Supper Italian, 1498 Milan, Santa Maria della Grazie |

Images of the Institution of the Eucharist

However, images of the Institution of the Eucharist are different. In many of these images the distinction from a Last Supper scene is very subtle. The figures are shown seated at the table, but the atmosphere is less that of a meal than of a Mass. Jesus may hold a Host, just as a priest does during Mass, He may even make gestures like those made by the priest. This is an image of the Last Supper as the First Mass.

|

Fra Angelico and Assistants, The Institution of the Eucharist Italian, c. 1441-1442 Florence, Museo di San Marco, Cell # 35 |

In some of them, neither Jesus nor the Apostles are seated. Jesus is shown standing and the Apostles are generally kneeling. It is the moment after the words of the Scriptures have been said. It is, in effect, an image of the Last Supper as the First Holy Communion.

|

| Fra Angelico, The First Communion of the Apostles From the Armadio degli Argenti Italian, c. 1451-1452 Florence, Museo di San Marco |

There are images of the Institution of the Eucharist that date from well before the Reformation (which began in 1515), such as the image at the top of the page, which dates from the late twelfth century. This predates even the institution of the feast of Corpus Christi.

Among these images is a page from the Très Riches Heures of the Duc of Berry, which shows Christ distributing Communion in the manner of a priest to the faithful at Mass. In the small picture that forms the illuminated capital letter is an image of Christ holding the chalice and elevating the Host.

|

| Jean Colombe, Institution of the Eucharist from the Tres Riches Heures du Duke de Berry French, c. 1485 Chantilly, Musée Condé MS DB 65, fol. 189v |

Another is a painting by the Flemish artist, Joos van Wassenhove, also identified as Just van Ghent, apparently painted in Italy.

|

Joos van Wassenhove, The Institution of the Eucharist Flemish, c. 1473-1475 Urbino, Galleria Nazionale delle Marche |

And there is also an example by Ercole de Roberti, in a tabernacle door probably from Ferrara in the 1490s. The tabernacle is the compartment in an altar or wall that is set aside to safeguard the consecrated hosts, which are the Body of Christ.

|

Ercole de'Roberti, The Insitution of the Eucharist Italian, 1490s London, National Gallery |

All of these pictures are dated to the last quarter of the 15th century (1475-1500).

However, there are many more dating from after 1515, indeed from the period known as the Counter-Reformation or the Catholic Reform. This is the period that includes the Council of Trent, which ran in three sessions from 1545-1563, and the period of Catholic recovery that followed it. It covers roughly the second half of the 16th century and the first half of the 17th century.

That there should be many images of the Institution of the Eucharist in the Counter-Reformation period is not surprising. One of the principal Reformation attacks on Catholicism was on Transubstantiation, the change of the bread and wine into the Body and Blood of Christ that happens during the Consecration of Mass. Protestants denied that anything special happened at that moment and insisted that the bread and wine remain merely bread and wine. They insisted that the liturgy has no cosmic dimensions and that the communion rite is only a sort of commemorative playacting.

Trent reaffirmed the age old Catholic belief in Transubstantiation and in the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist following the Consecration.

After Trent, artists were encouraged through commissions and instructions to paint pictures that would reaffirm and transmit Catholic teachings visually. And among the artists who responded with appropriate images were:

Federico Barocci, in an altarpiece from the Aldobrandini Chapel in the church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva in Rome.

|

Federico Barocci, The Insitution of the Eucharist Italian, 1608 Rome, Church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva |

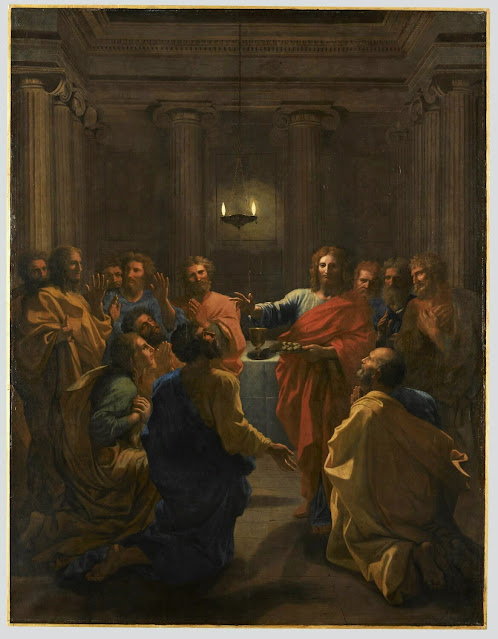

And Nicolas Poussin, in second of his two series of paintings of the Seven Sacraments.

|

Poussin, The Institution of the Eucharist From the Second Series of the Seven Sacraments French, 1641 Paris, Musée du Louvre |

At the end of the nineteenth century the French painter, James Tissot, took up the theme in his well researched Biblical illustrations.

|

James Tissot, The Institution of the Eucharist French, c. 1886-1894 New York, Brooklyn Museum |

These images show the profound respect for the sacramental Species due to these Elements (Bread and Wine) when transformed into the Body and Blood of Christ.

Although images of the Last Supper continued to be produced both in Catholic and in Protestant countries after the Reformation, the Insitution of the Eucharist images are not found in the Protestant countries.

Although images of the Last Supper continued to be produced both in Catholic and in Protestant countries after the Reformation, the Insitution of the Eucharist images are not found in the Protestant countries.

© M. Duffy, 2011, images refreshed and expanded 2024.

Scripture texts in this work are taken from the New American Bible,

revised edition © 2010, 1991, 1986, 1970 Confraternity of Christian Doctrine,

Washington, D.C. and are used by permission of the copyright owner. All Rights

Reserved. No part of the New American Bible may be reproduced in any form

without permission in writing from the copyright owner.

No comments:

Post a Comment