,%20c.%201425-1435+New%20York,%20Pierpont%20Morgan%20Library_MS%20M%20720,%20fol.%203rb_2.jpg) |

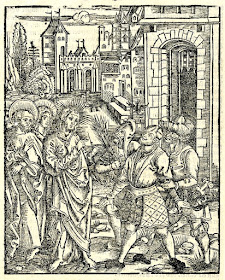

| Jesus Casting Out a Demon From New Testament Illustrations German (Upper Rhine), c. 1425-1435 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M 720, fol. 3r |

“Then they came to Capernaum,

and on the sabbath Jesus entered the

synagogue and taught.

The people were astonished at his teaching,

for he taught them as one having authority

and not as the scribes.

In their synagogue was a man with an unclean

spirit;

he cried out, "What have you to do with

us, Jesus of Nazareth?

Have you come to destroy us?

I know who you are—the Holy One of

God!"

Jesus rebuked him and said,

"Quiet! Come out of him!"

The unclean spirit convulsed him and with a

loud cry came out of him.

All were amazed and asked one another,

"What is this?

A new teaching with authority.

He commands even the unclean spirits and

they obey him."

His fame spread everywhere throughout the

whole region of Galilee.”

Mark

1:21-28, Gospel for the Fourth Sunday in Ordinary Time, Year B

Mark’s

Gospel contains two similar yet different accounts of the healing of a

possessed man by Jesus. The first one is

the Gospel for this Sunday, the Fourth Sunday in Ordinary Time quoted

above. The second, longer and better

known account, is the Gospel that will be read at the Masses for the following

day, Monday, January 29, 2018:

“Jesus and

his disciples came to the other side of the sea,

to the

territory of the Gerasenes.

When he got

out of the boat,

at once a

man from the tombs who had an unclean spirit met him.

The man had

been dwelling among the tombs,

and no one

could restrain him any longer, even with a chain.

In fact, he

had frequently been bound with shackles and chains,

but the

chains had been pulled apart by him and the shackles smashed,

and no one

was strong enough to subdue him.

Night and

day among the tombs and on the hillsides

he was

always crying out and bruising himself with stones.

Catching

sight of Jesus from a distance,

he ran up

and prostrated himself before him,

crying out

in a loud voice,

"What

have you to do with me, Jesus, Son of the Most High God?

I adjure you

by God, do not torment me!"

(He had been

saying to him, "Unclean spirit, come out of the man!")

He asked

him, "What is your name?"

He replied,

"Legion is my name. There are many of us."

And he

pleaded earnestly with him

not to drive

them away from that territory.

Now a large

herd of swine was feeding there on the hillside.

And they

pleaded with him,

"Send

us into the swine. Let us enter them."

And he let

them, and the unclean spirits came out and entered the swine.

The herd of

about two thousand rushed down a steep bank into the sea,

where they

were drowned.

The

swineherds ran away and reported the incident in the town

and

throughout the countryside.

And people

came out to see what had happened.

As they

approached Jesus,

they caught

sight of the man who had been possessed by Legion,

sitting

there clothed and in his right mind.

And they

were seized with fear.

Those who

witnessed the incident explained to them what had happened

to the

possessed man and to the swine.

Then they

began to beg him to leave their district.

As he was

getting into the boat,

the man who

had been possessed pleaded to remain with him.

But Jesus

would not permit him but told him instead,

"Go

home to your family and announce to them

all that the

Lord in his pity has done for you."

Then the man

went off and began to proclaim in the Decapolis

what Jesus

had done for him; and all were amazed.”

Matthew

5:1-20

The curing

of these possessed individuals is not one of the most frequently depicted

miracles of Jesus in art. Possibly this

is because the representation of a possessed individual was distasteful to

artists or their patrons, or possibly just because it is more difficult to

depict the possessed than it is to depict someone who is a leper or blind or

paralyzed. There are both clinical and

cultural signs that signal these other conditions. Possession or madness is a bit more difficult. Nevertheless, some artists did endeavor to

depict these scenes, especially the second one, where the presence of the herd

of swine offers an exterior clue to the subject being imaged.

The first

image I have been able to locate comes from a cycle of pictures of the life of

Christ from the church of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna. This basilica was built at the beginning of

the sixth century by the Ostrogothic King Theodoric, who had deposed the last

of the Roman Emperors of the West. Like

many of the Gothic tribes which had invaded the western Empire, the Ostrogoths

were Arian Christians. That is, they

believed Jesus to be, not the Second Person of the Holy Trinity, but to be a

created being, separate from and inferior to God.1 For a

while it looked as though this heresy might overwhelm the orthodox belief, held

from the Apostles on, that Jesus is co-equal and consubstantial with the Father

and the Holy Spirit in the three-fold mystery of the Triune Godhead. Orthodox believers in both the Greek and

Latin speaking branches of what was still one, undivided Church, eventually

prevailed in the controversy and Sant’Apollinare was reconsecrated and

partially rebuilt in the second half of the sixth century by the Eastern Roman

(Byzantine) Emperor Justinian.

|

| Jesus Heals the Possessed Man of Gerasa Byzantine, c. 526 Ravenna, Sant'Apollinare Nuovo |

The image

from Sant’Apollinare shows the end of the passage from Matthew 5 in which the

formerly possessed man kneels in thanksgiving before Jesus, “clothed and in his

right mind” (Matthew 5:15), as the swine into which the legion of evil spirits

formerly infesting him had fled, as they rush into the water to drown. Standing behind Jesus is a disciple, who may

represent the Evangelist Matthew, raising his hand in a gesture of astonishment

as he looks directly at the viewer.

The next

image I located comes from another imperial court, this time in northern

Europe. In the tenth century the

Ottonian Emperors governed the remains of the empire constructed in western

Europe by Charlemagne. And, in the late

tenth century, the Emperor Otto III presented a series of ivory plaques to the

cathedral of Magdeburg, which represent some of the finest European ivory

carving of the early middle ages.2 It

shows the moment at which the demons who have afflicted the Gerasene man come

out of him. A spirit is issuing from his

mouth as his friends attempt to restrain him.

Behind the man stand the swine, not yet infested by the evil

spirits. Behind Jesus we see Peter,

holding the keys, and the other Apostles.

|

Christ Healing the Possessed Man of Gerasa Ottonian, c. 968 Darmstadt, Hessisches Landesemuseum |

These images

laid the ground for a series of medieval images, in wall painting and

manuscripts, for the scene of the casting out of demons. Most, though not all, include the pigs and

are, therefore, clear references to the passage in Matthew 5. Those that do not may be seen as references

to the episode in Matthew 7.

|

| The Healing of the Gerasene Demoniac German, c. 980 Oberzell, Church of Saint Georg |

,%20First%20Quarter%20of%20the%2011th%20Century_Darmstadt,%20Landesbibliothek_MS%201640,%20fol.%2076.jpg) |

| Jesus Casting Out a Demon From the Hitda Codex German (Cologne), First Quarter of the 11th Century Darmstadt, Landesbibliothek MS 1640, fol. 76 |

|

| Jesus Curing the Gerasene Demoniac From the Gospel Book of Otto III German (Reichenau), c. 1000 Munich, Bayerische StaatsBibliothek MS Clm 4453, fol. 43 (detail) |

,%20c.%201430_The%20Hague,%20Koninklijk%20Bibliotheek_MS%20KB%2078%20D%2038%20II,%20fol.%20157v_2.jpg) |

| Claes Brouwer and Others. Healing of the Possesed Man at Gerasa From a Book of Hours Dutch (Utrecht), c. 1430 The Hague, Koninklijk Bibliotheek MS KB 78 D 38 II, fol. 157v |

|

| Jesus Curing the Possessed Men of Gerasa From the Ottheinrich-Bibel German, c. 1430 Munich, Bayerische StaatsBibliothek MS Cgm 8010, fol. 40 |

With the

advent of the Renaissance the pigs tend to disappear and the focus becomes more

closely focused on the struggling possessed man (usually restrained by friends) and Jesus.

|

| Unknown Master of Delft, Jesus Casting Out a Demon Dutch, 1503 Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum |

|

| Hans Franck, Jesus Curing a Demoniac German, 1517 London, Trustees of the British Museum |

|

| Sebald Beham, Jesus Curing a Demoniac German, 1530 London, Trustees of the British Museum |

|

| Tobias Stimmer, Jesus Casting Out a Demon German Swiss, c. 1560-1564 London, Trustees of the British Museum |

It isn’t

until the end of the sixteenth century that the pigs return to enable us to

clearly identify those images that illustrate Matthew 7. However, neither passage seems to have

dominated and artists were able to include whatever context and details they

wished. In addition, the detail of the demon exiting from the mouth of the possessed becomes much less common.

During these

years the setting was opened up and the dramatic confrontation was placed in a

well-defined landscape peopled by many subsidiary figures.

|

| Friedrich Christoph Steinhammer, Jesus Casting Out a Demon German, 1612 London, Trustees of the British Museum |

|

| Paul Kreutzberger, Jesus Casting Out a Demon From Illustrations for a Bible German, c. 1620-1660 London, Trustees of the British Museum |

|

| Anonymous, Jesus Casting Out a Demon Italian, c. 1650 London, Trustees of the British Museum |

|

| Francois Chauveau, Jesus Curing the Possessed Man of Capernaum French, c. 1670-1676 London, Trustees of the British Museum |

Late seventeenth-century artist Francois Chauveau apparently illustrated both passages from Saint Matthew's Gospel with these two pictures.

|

| Francois Chauveau, Jesus Curing the Possessed Man of Gerasa French, c. 1670-1676 London, Trustees of the British Museum |

| ||

| Aureliano Milani_Healing of the Possessed at Gerasa Italian, c. 1700 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art

|

Finally, at

the end of the nineteenth century, in his first great Biblical series of

pictures, the French artist James Tissot, painted a highly realistic

scene.

|

| James Tissot, The Two Possessed Men of Gerasa French, c. 1886-1894 New York, Brooklyn Museum |

Based on his residence in what

was then Palestine Tissot was able to create a believable vision of the event,

where two naked, gaunt and wild-haired men are confronted in their madness by

Jesus and his disciples. In the

background a swineherd tends the pigs that will shortly become infested and

hurl themselves to their deaths in the sea below.

©

M. Duffy, 2018, pictures updated 2024.

- This view of the nature of Jesus is held today by the Jehovah’s Witnesses.

- For more information on this series of plaques and for Ottonian art in general see: The Metropolitan Museum of New York at https://metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/467730 and the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History at https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/ht/06/euwc.html

Excerpts from the Lectionary for Mass for Use in the Dioceses of the United States of America, second typical edition © 2001, 1998, 1997, 1986, 1970 Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, Inc., Washington, DC. Used with permission. All rights reserved. No portion of this text may be reproduced by any means without permission in writing from the copyright owner.

No comments:

Post a Comment