|

| Traditio legis Central Image From the Upper Level of the Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus Roman, c. 359 Vatican City, Museo Storico del Tesoro della Basilica di San Pietro |

"Jesus appeared to the Eleven and said to them:“Go into the whole world and proclaim the Gospel to every creature.Whoever believes and is baptized will be saved; whoever does not believe will be condemned."

Mark 16:15-16 (Gospel for the Feast of Saint Mark, April 25)

The subject of the first verse of today’s reading, the instruction to the Apostles to go into the whole world, is the scene called the “traditio legis”. It is a scene well-known from early Christian times through the Middle Ages, but seems to have disappeared from the iconography of later times. Scholarly opinion is very divided over exactly what the imagery means. Is it, as I suggest, related to the commission to the Apostles? Is it a reference to the worldly power of the Church, which was just beginning to grow? Did it have an eschatological meaning, referring to the end of days? Was it an assertion of the present day status of the Church on earth? Was it an image of Paradise, demonstrating the current state of Christ and the Apostles?1 Or, as I am also inclined to think, a combination of all of these. Sometimes, we try too hard to affix a specific meaning to an image, while the realm of images is much more flexible and multifaceted than that.

Traditio legis translates as “the giving of the law”. In the case of Christianity it refers to the instruction of Jesus to the Apostles, which is the subject of the quotation from the Gospel of Mark cited above. Currently, the most famous early Christian appearance of the traditio legis is on the central panel of the upper row of scenes from the life of Christ on the Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus, now in the Vatican Museum. The sarcophagus dates from the mid-fourth century (359), just a few decades from Constantine’s proclamation of the Edict of Milan, which made Christian practice legal. Prior to that time, Christian practice was illegal, sometimes tolerated, sometimes persecuted. With Constantine’s edict, subsequent adoption of Christianity as the religion of the Empire, and his building of the great basilicas in Rome and Jerusalem, we begin to see Christian art emerge from the shadow of the catacombs.

Indeed, it is the children of Constantine that may have been the very earliest supporters of the image of the Traditio legis. Junius Bassus was a close associate, serving in high office within Rome under Constantine I and his three sons, Constintine II, Constans and Constantius II, in whose reign he died. Another early image is that from the mausoleum of Constantine's daughter, Constantia, decorated at about the same date as the Junius Bassus sarcophagus. Also, the original mosaic decoration of the apsidal dome of Old Saint Peter's, begun under Constantine I and completed during the reign of Constantius II is presumed to have been a Traditio legis image. 2

|

| Reconstruction of the first mosaic of the Apse of Old Saint Peter's by Tilmann Buddensieg (1959) Roman, Mid-4th Century |

The first image available was the famous statue of the first Emperor, Augustus, known as the Augustus Prima Porta. The statue was originally made of bronze, probably sometime around the year 0 in the Christian calendar. It has vanished, but we know exactly what it looked like from the marble copy made for Augustus' wife, Livia, which stood in her villa. It was discovered in 1863 during an excavation of the villa and is now in the Vatican Museums.

|

| Augustus from Prima Porta Roman, Early 1st Century AD (Probably14-29) Vatican, Vatican Museums, New Wing of the Chiaramonti Museum |

The second image was a more recent one. This is the colossal statue of the Emperor Constantine made sometime between 312 and 320. It originally stood in the Basilica built by his defeated rival, Maxentius. Fragments of it still exist and are currently in the collection of the Capitoline Museum in Rome. They are truly monumental, as this reconstruction suggests.

|

| Computer reconstruction of colossal statue of Constantine which stood in the Basilica of Maxentius Roman, 4th century Fragments in the Capitoline Museum, Rome |

|

| Upper Tier of Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus Roman, 359 Vatican, St. Peter's Basilica, Museo Storico del Tesoro della Basilica di San Pietro |

Quite a number of representations of the traditio legis were made during the fourth and fifth centuries. While researching this article I was actually surprised by how many there are.

Not surprisingly these images derive from the two discussed above.

Standing (Augustus as persuader and lawgiver)

|

| Traditio Legis Mosaic From the Mausoleum of Santa Costanza,(Daughter of Constantine I) Roman, c. 350 Rome, Church of Santa Costanza |

|

| Fragment of a Marble Tomb Relief with Christ Giving the Law Roman, Late 300s New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

|

| Front of a Sarcophagus Peter Preaching, Peter Led to Martyrdom, the Traditio Legis, Christ Before Pilate, Pilate Washing Roman, c. 380-400 Vatican City, Museo Pio Cristiano |

|

| Central Portion of the Front of a Sarcophagus with the Traditio legis Roman, 4th Century Vatican, Vatican Museums, Museo Pio Cristiano |

|

| Nea Herakleia Reliquary Greco-Roman, Late 4th-Early 5th Century Thessaloniki, Museum of Byzantine Culture |

|

| Sarcophagus Frontal with the Traditio Legis Roman, c. 390-400 Paris, Musée du Louvre |

|

| Sarchopagus Frontal with the Traditio Legis Originally from Church of San Giovanni Battista, Late Roman, Early 5th Century Ravenna, Museo Nazionale |

|

| Traditio Legis Mosaic From the Baptistery Dome Roman, c. 362-409 Naples, Church of San Giovanni in Fonte, Baptistery |

|

| Apse Mosaic with Traditio Legis Late Antique (Roman), c. 526-530 Rome, Basilica of Saints Cosmas and Damian |

|

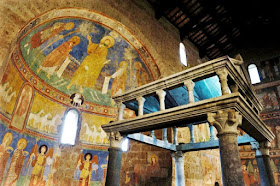

| Apse wall painting with Traditio legis Italian, Early 12th Century Tivoli, Church of San Silvestro |

|

| Traditio Legis Apse Fresco Italian, c. 1120-1130 Castel Sant'Elia, Basilica |

Seated (Constantine as powerful lawgiver)

However, following the barbarian take over of the Western Roman Empire the use of the Traditio legis image largely tapers off.Intermediate Images in the Early Middle Ages

There are a series of intermediate images that record the transformation of the Traditio legis into something else. They begin to appear in the domain of the Carolingian Empire and later in the German Ottonian Empire and associate the gestures of the Traditio legis with a slightly different symbolic meaning.

| ||

|

|

| Traditio Legis Plaque from a Book Cover German (Ottonian), c. 950 Berlin, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin MS theol. lat. |

|

| Plaque with Christ Presenting the Keys to Saint Peter and the Law to Saint Paul German, c. 1150-1200 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Cloisters Collection |

Transformation in the Later Middle Ages and Beyond

The image of the Traditio legis was permanently affected by the end of the Roman Empire in the West. Apart from the cited examples in Ottonian art, it morphed into something different, sometimes called the Traditio clavium or the Giving of the Keys to Peter. This is a narrative subject reflecting the Biblical passage of Matthew 16:13-20 in which Peter correctly answers Jesus' question "Who do people say the Son of Man is?" and is rewarded with a new name (Rock) and confirmed as the foundation stone of the Church on earth and the possessor of the keys to heaven. |

| Meister_des_Perikopenbuches, Giving of the Keys From the Book of Pericopes of Emperor Henry II German (Reichenau), c. 1007-1012 Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek MS Clm 4452, fol. 142v |

|

| Giving of the Keys English, c. 1170-1180 Paris, Musée du Louvre |

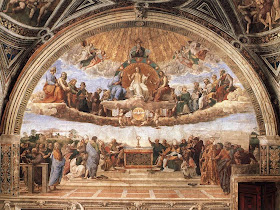

It also persists, transformed into the familiar image of the Last Judgment (or Apocalypse) seen through the centuries, from the facades of the great Romanesque and Gothic cathedrals to the wall of the Sistine Chapel, and adopted by Raphael for the beautiful Disputà (Disputation on the Blessed Sacrament, of 1509) in the Vatican.

|

| Apocalypse Tympanum from the south portal at Moissac French, 1130-1140 Moissac, Abbey Church of Saint-Pierre |

|

| Michelangelo, Last Judgment, Central Image Italian, c. 1537-1541 Vatican City, Apostolic Palace, Sistine Chapel |

|

| Raphael, Disputa From the Stanza della Segnatura Italian, 1509 Vatican City, Vatican Museums, Apostolic Palace |

© M.

Duffy, 2008, totally revised 2020

1 Several theories regarding the meaning of the Traditio legis have been proposed in recent years, including the one which I present. For an overview see: Armin F. Bergmeier, "The Traditio Legis in Late Antiquity and Its Afterlives in the Middle Ages," Gesta, Volume 56, no. 1 (Spring 2017), p. 33.

2 See Richard Krautheimer. "A Note on the Inscription in the the Apse of Old Saint Peter's", Dumbarton Oaks Papers, Volume 41, Studies on Art and Archeology in Honor of Ernst Kitzinger on His Seventy-Fifth Birthday, 1987, pp. 317-320.

Also: Ivan Foletti and Irene Quadri, "L'immagine e la sua memoria L'abside di Sant'Ambrogio a Milano e quella di San Pietro aRoma nel Medioevo", Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, Vol.76. Bd. H. 4, 2013, pp. 475-492.

Finally, another interesting study of the decoration of early apses, though not directly related to this discussion, can be found in: J.-M. Spieser, The Representation of Christ in the Apses of Early Christian Churches", Gesta, Vol. 27, No. 2, 1998, pp. 63-73.

3 For discussions of this idea see: Bergmeier above as well as:Peter Franke, "Traditio legis und Petrusprimat: Eine Entgegnung auf Franz Nikolasch", Vigiliae Christianae, Vol. 26, No. 4, December, 1972, pp. 263-271.

1 Several theories regarding the meaning of the Traditio legis have been proposed in recent years, including the one which I present. For an overview see: Armin F. Bergmeier, "The Traditio Legis in Late Antiquity and Its Afterlives in the Middle Ages," Gesta, Volume 56, no. 1 (Spring 2017), p. 33.

2 See Richard Krautheimer. "A Note on the Inscription in the the Apse of Old Saint Peter's", Dumbarton Oaks Papers, Volume 41, Studies on Art and Archeology in Honor of Ernst Kitzinger on His Seventy-Fifth Birthday, 1987, pp. 317-320.

Also: Ivan Foletti and Irene Quadri, "L'immagine e la sua memoria L'abside di Sant'Ambrogio a Milano e quella di San Pietro aRoma nel Medioevo", Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, Vol.76. Bd. H. 4, 2013, pp. 475-492.

Finally, another interesting study of the decoration of early apses, though not directly related to this discussion, can be found in: J.-M. Spieser, The Representation of Christ in the Apses of Early Christian Churches", Gesta, Vol. 27, No. 2, 1998, pp. 63-73.

3 For discussions of this idea see: Bergmeier above as well as:Peter Franke, "Traditio legis und Petrusprimat: Eine Entgegnung auf Franz Nikolasch", Vigiliae Christianae, Vol. 26, No. 4, December, 1972, pp. 263-271.

Excerpts from the Lectionary

for Mass for Use in the Dioceses of the United States of America, second

typical edition © 2001, 1998, 1997, 1986, 1970 Confraternity of

Christian Doctrine, Inc., Washington, DC. Used with permission. All rights

reserved. No portion of this text may be reproduced by any means without

permission in writing from the copyright owner.