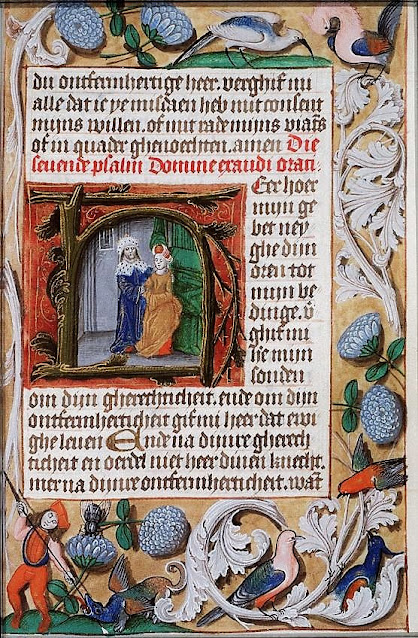

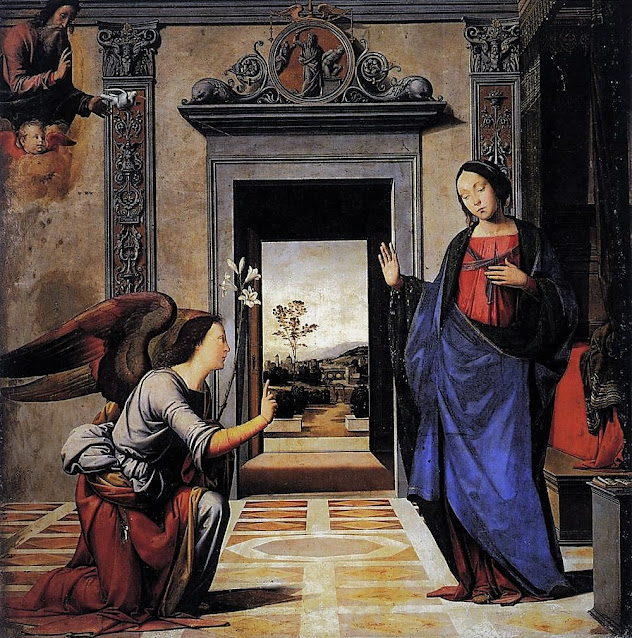

Joos van Cleve, Annunciation

Flemish, c. 1525

New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Note: This essay should be read in conjunction with the one that precedes it.

|

| Joos van Cleve, Annunciation Flemish, c. 1525 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

Note: This essay should be read in conjunction with the one that precedes it.

Another location chosen for some of the most well-known images set in the domestic interior are those which show the scene taking place in Mary’s bedroom.

This setting warrants special attention. The bedroom is a distinctive space in any home. It is the withdrawal room, the inner chamber, the privy chamber, the secret space where only the occupant and his/her immediate family and friends and closest servants are allowed. It can be a place of solitude, if desired. And it has intimate ties with a human person’s experience of sleep, as well as with birth, death, love, and thought. But, with a few notable exceptions, it is not a very frequent setting for important pictures.

Chief among these exceptions are the so-called Arnolfini Portrait by Jan van Eyck and the series of Annunciation scenes we will be looking at.

|

| Jan van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait Flemish, 1434 London, National Gallery |

In discussions of the Arnolfini Portrait I have often seen statements to the effect that the room is not so much a bedroom as a reception room. Reception rooms of this period, we are told, often contained a large and ornate bed, which might or might not be in actual use, but functioned primarily as a status symbol. So far, I have seen no evidence cited for the source of this kind of statement, and it may be true.

However, I suspect that the picture is actually set in a that specialized room we call the bedroom.

Bedrooms have been in existence for thousands of years. In the world of ancient Rome, for instance, the cubiculum was a smallish room set aside as a sleeping chamber.

|

| Cubiculum (bedroom) from the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor Roman (Late Republic), c. 50-40 BC New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

And, even though in the early middle ages, most of the members of a household bedded down in the main hall, there was usually some separate room for the lord of the manor and his family. As time and wealth returned to Roman levels, individual houses went from being one room hovels to having specialized rooms for different functions and the bedroom as we know it was reborn.

The well-to-do merchants and members of the nobility who commissioned works such as the Arnolfini Portrait and the majority of images of the Annunciation were affluent enough to have dwellings that probably included at least one, if not several bedrooms (as for example in a dollhouse made toward the end of the period which saw the greatest number of Annunciation images set in the bedroom of Mary).

The well-to-do merchants and members of the nobility who commissioned works such as the Arnolfini Portrait and the majority of images of the Annunciation were affluent enough to have dwellings that probably included at least one, if not several bedrooms (as for example in a dollhouse made toward the end of the period which saw the greatest number of Annunciation images set in the bedroom of Mary).

Depictions of the Bedroom -- 14th through 17th Centuries

While thinking about this issue I decided to review what kinds of pictures were actually set in the bedroom during this same period. I surveyed multiple museum and library websites to gather a good sample.

What I found was not surprising. Images that were clearly set in separate sleeping chambers, or bedrooms, illustrated the following topics:

Sleep

What I found was not surprising. Images that were clearly set in separate sleeping chambers, or bedrooms, illustrated the following topics:

Sleep

Birth

|

| Evrard d'Espinques, A Doctor Examining Urine from De Proprietatibus rerum by Barthelemy l'Anglais Franch (Ahun), 1480 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 9140, fol. 120v |

|

| Master of the Pesaro Crucifix, St. Cecilia and Her Husband, Valerian, Being Crowned by an Angel Italian, c. 1375-1380 Philadelphia, Museum of Art |

|

| Brangain Sleeping with King Mark in Place of Isolde from Tristan de Leonois French (Central), c. 1470 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 112 (1), fol. 244v |

|

| Masters of the Dark Eyes, David and Bathsheba in Their Bedroom from a Book of Hours Dutch, c. 1490 The Hague, Koninklijk Bibliotheek MS KB 76 G 9, fol. 150r |

|

| Jupiter and Danäe from Histoire des Troyes by Raoul Lefevre Flemish, 1495 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 22552, fol. 49v |

|

| Jean de Brosse and Louise de Laval in Prayer in their Bedroom from Histoire de Jean III de Brosse et de sa femme Louise de Laval French, c. 1500 Chantilly, Musée Condé MS 388, fol. 14r |

\

|

| Alexander the Great Dictating His Will from Histoire d'Alexndre by Jan Wauquelin Flemish (Bruges), 1450 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 9342, fol. 210v |

|

| Guglielmo Giraldi, Dido Carried Fainting to Her Bed from The Aeneiad by Virgil Italian (Ferrara), 1458 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 7939 A, fol. 102 |

|

| Pieter Lastman, Wedding Night of Tobias and Sarah Dutch, 1611 Boston, Museum of Fine Arts |

|

| Eustache Le Sueur, Rape of Tamar French, c. 1640 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art and occasionally, just Thinking. |

These comments on the depiction of the uses of the bedroom as a setting help us to sense the thought underlying these popular paintings of the Annunciation taking place in the bedroom or close enough to the bedroom to offer a glimpse of the bed.

|

| Annunciation from Legenda aurea France (Paris), Beginning of the 15th Century Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 242, fol. 1 |

|

| Pere Serra, Annunciation Spanish, 1400-1405 Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera |

|

| Gentile da Fabriano, Annunciation Italian, c. 1425 Vatican, Pinacoteca |

|

| Roger van der Weyden, Annunciation Flemish, c.1440 Paris, Musée du Louvre |

What they tell us is that, at the moment Gabriel appeared, Mary was situated in a private space where she was engaged in an activity, which may have been reading, or working on some needlework, or most frequently, praying. The room may be well-furnished or extremely simple, but it contains a bed, frequently with hangings, or such a bed can be clearly glimpsed in an adjoining space.

|

| Master of the Flemish Boethius, Annunciation from Vita Jesu Christi Belgian (Ghent), 1480 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francaise 181, fol. 15 |

|

| Annunciation from a Book of Hours Naples, 1483 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M 1052, fol. 13r |

|

| Sandro Botticelli, Annunciation Italian, c.1485 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Lehman Collection |

|

| Domenico Ghirlandaio, Annunciation Italian, 1486-1490 Florence, Santa Maria Novella, Tornabuoni Chapel |

|

| Hans Memling, Annunciation German, 1489 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

|

| Jean Hey, Master of Moulins, Annunciation French, c. 1490-1495 Chicago, Art Institute |

In all but the most recent (19th- and 20th century paintings) the bed is shown as made up, not in disarray, frequently covered with a bedspread. Occasionally, Mary is shown as seated on the bed. But, mostly, she is seated elsewhere or is kneeling at a prayer stand.

|

| Filippino Lippi, Annunciation Italian, Mid 1490s St. Petersburg, State Hermitage Museum |

|

| Giovanni Battista Cima da Conegliano, Annunciation Italian, 1495 St. Petersburg, State Hermitage Museum |

|

| Master of Unicorn Hunt, Annunciation from a Book of Hours French (Paris), 1495-1499 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M 1110, fol. 37r |

|

| Fra Bartolomeo, Annunciation Italian, 1497 Volterra, Cathedral |

|

| Annunciation Leaf from a Book of Hours Flemish (Ghent-Bruges), c.1500-1525 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

What are we to make of this? There is the contrast between the ordinary, domestic, calm and the sudden arrival of this messenger from outside of time and space. In some pictures, the artist included some indication of the action of the Holy Spirit, by including a dove or even a tiny Christ Child traveling on a sunbeam. God the Father may be seen hovering in space, eager to hear her reply. Among the northern artists there may be the inclusion of hidden symbolism related to the Incarnation, which is the event that takes place as soon as Mary says

|

| Bernardo Zenale, Annunciation Italian, 1510-1512 Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera |

|

| Annunciation Dutch, c. 1520 Berlin, Gemäldegalerie der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin |

|

| Pieter Coecke van Aelst, Annunciation Right wing of a triptych Flemish, 1530-1540 Madrid, Museo del Prado |

|

| Lorenzo Lotto, Annunciation Italian, 1534-1535 Recanati, Pinacoteca Civica |

|

| Marcellus Coffermans, Annunciation Dutch, c. 1549-1578 Glasgow, The Burrell Collection |

|

| Francesco Salviati, Annunciation Italian, c. 1550 Rome, Church of San Marcello al Corso |

|

| Girolamo Mazzola Bedoli, Annunciatin Italian, c. 1550 Naples, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte |

(These two paintings, by Salviati and Bedoli, clearly demonstrate the way in which Mannerist painters departed from straightforward story telling by employing odd, spiraling poses that often obscured the narrative of their images.)

|

| Marten de Vos, Annunciatin Flemish, 1569 Celle, Schlosskapelle |

|

| Annunciation Woodcut From Luther Betbuchlinof German, 1573 New York, New York Public Library, Spencer Collection MS NYPL Spencer 108

Early Protestant books retained the Catholic imagery.

|

However, I think that it is the bed itself, with its intimate connotations, that is the biggest symbol. For here is a moment of conception that is not taking place in the normal manner. Mary is alert, alone and actively engaged on her own, in her own space. Her conscious and conscientious replies to the angel’s astonishing greeting and announcement, including her skeptical question ““How can this be, since I have no relations with a man?” (Luke 1:34), suggest that she is fully aware of what has been said and, reasonably, astonished at its implications. But her final, calm acceptance is mirrored in the undisturbed neatness of the bed and its coverings. This was no carnal, earthly act of conception, but a holy one.

And yet, there is a certain sense in which this

is, in a mystical sense, a marriage, not between a man and a woman, but between

God and humanity. And, in that sense,

the bed is indeed a kind of marriage bed.

|

| Federico Barocci, Annunciation Italian, 1582-1584 Vatican City, Pinacoteca Vaticana |

|

| Tintoretto, Annunciation Italian, 1583-1587 Venice, Scuola Grande di San Rocco |

|

| Peter Candid, Annunciation Flemish, c. 1585 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

|

| Domenico Passignano, Annunciation Italian, 1590-1591 Rome, Church of Santa Maria in Vallicella |

|

| Francesco Vanni, Annunciation Italian, 1592 Torrita di Siena, Church of Saints Flora and Lucilla |

|

| Agostino Carracci, Annunciation Italian, c.1600 Paris, Musée du Louvre |

|

| Anonymous, Annunciation Possibly Flemish, c. 1600 London, Guildhall Art Gallery This is the sole example I found of a bed placed in what is obviously a reception room and not a proper bedroom. |

Setting the scene of the Annunciation in Mary’s bedroom was, without doubt, the frequent choice of artists and their patrons from the about the middle of the fifteenth to the middle of the seventeenth centuries, to be revived somewhat in the late nineteenth century.

|

| Peter Paul Rubens, Annunciation Flemish, c. 1609 Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum |

|

| Giovanni Lanfranco Italian, 1610-1630 St. Petersburg, State Hermitage Museum |

|

| Pieter Lastman, Annunciation Dutch, 1618 St. Petersburg, State Hermitage Museum |

|

| Frans Francken II, Annuncition Flemish, c. 1620 Chicago, Art Institute |

|

| Charles Poerson, Annunciation French, 1623-1653 Paris, Musée Carnevalet |

|

| Orazio Gentileschi, Annunciation Italian, c.1623 Turin, Galleria Sabauda |

|

| Guido Reni, Annunciatin Italian, c. 1629 Paris, Musée du Louvre |

|

| Sassoferrato, Annuncation Italian, c. 1630 Paris, Musée du Louvre |

|

| Philippe de Champaigne, Annunciation French, c.1645 London, Wallace Collection |

|

| Luca Giordano, Annunciation Italian, 1672 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

|

| Jean Jouvenet, Annunciation French, 1685 Rouen, Musée des Beaux-Arts |

|

| Eugene Delacroix, Annunciation French, 1841 Paris, Musée du Louvre, Musée National Eugene-Delacroix |

|

| Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Ecce Ancilla Domini English, 1850 London, Tate |

|

| James Tissot, The Annunciation French, 1886-1894 New York, Brooklyn Museum |

|

| Henry Ossawa Tanner, Annunciation American, 1898 Philadelphia, Museum of Art |

So, as we have seen, artists have been inspired to depict the Annunciation in many different ways, from the simplest forms and compositions to the most complex. All, however, reflect on the astonishing moment in which Mary’s "yes" to God’s surprising request initiated the Incarnation, in which “the Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us” (John 1:14) and the world began anew.

© M. Duffy, 2017

Scripture texts in this work

are taken from the New American Bible, revised edition © 2010,

1991, 1986, 1970 Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, Washington, D.C. and are

used by permission of the copyright owner. All Rights Reserved. No part of the

New American Bible may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing

from the copyright owner.

- For information on the Arnolfini Portrait see : https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/jan-van-eyck-the-arnolfini-portrait as well as http://www.dailymail.co.uk/home/you/article-2036955/The-Arnolfini-portrait-Jan-van-Eyck-The-mystery-National-Gallery-masterpiece.html and https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2000/apr/15/art for some recent non-specialist comments.

- And see: Panofsky, Erwin. “Jan Van Eyck's Arnolfini Portrait.” The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, vol. 64, no. 372, 1934, pp. 117–127 for the initial suggestion about the meaning of the portrait by Erwin Panofsky, as well as:

- Carrier, David. “Naturalism and Allegory in Flemish Painting.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, vol. 45, no. 3, 1987, pp. 237–249,

- Baldwin, Robert. “Marriage as a Sacramental Reflection of the Passion: The Mirror in Jan Van Eyck's ‘Amolfini Wedding.’” Oud Holland, vol. 98, no. 2, 1984, pp. 57–75,

- Bedaux, Jan Baptist. “The Reality of Symbols: The Question of Disguised Symbolism in Jan Van Eyck's ‘Arnolfini Portrait.’” Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art, vol. 16, no. 1, 1986, pp. 5–2,

- Also see: Harbison, Craig. “Iconography and Iconology.” Early Netherlandish Paintings: Rediscovery, Reception and Research, edited by Bernhard Ridderbos et al., Amsterdam University Press, 2005, pp. 378–406 for a contemporary review of the whole issue of symbolic meanings in the art of the fifteenth century in northern Europe

2. Although it deals with a different work of art, see Freeman, Margaret B. “The Iconography of the Merode Altarpiece.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, vol. 16, no. 4, 1957, pp. 130–139 for information on some of the possible symbolism associated with paintings of the Annunciation. See also: Carrier, David. op. cit. and Harbison, Craig. op. cit.

No comments:

Post a Comment