,%20c.%201425-1475_London,%20British%20Library_MS%20Additional%2039663,%20fol.%2018.jpg) |

| Saint Clare Cutting from a Missal Italian (Lombardy), c. 1425-1475 London, British Library MS Additional 39663, fol. 18r |

Clare of Assisi is one of the greatest female saints of the Middle Ages and, possibly, one of the most overlooked in the modern world. She was the first woman to follow Saint Francis of Assisi on his quest for closeness to God through perfect poverty, becoming the foundress of the second Franciscan Order, known originally as the Poor Ladies, but quickly becoming known as the Poor Clares. However, her importance is not merely as a follower, but as a pioneer of a new kind of religious life for women, one for which she had to face considerable opposition during her life.

Clare was born in 1193 or 1194 to Favorino Scifi and

Ortolana di Fiumi. Her parents appear to

have belonged to the Italian nobility, with her father apparently bearing the

title of Count of Sasso-Rosso. She grew

up in the town of Assisi in the Umbrian region of Central Italy. Virtually nothing is known of her childhood

but, in 1212 at around the age of eighteen, her life changed dramatically. In that year Saint Francis preached a series

of Lenten sermons at the church of San Giorgio in Assisi. The sermons touched Clare’s heart and roused

in her a determination to live her life according to the principles by which

Francis was living, that is, total poverty and apostolic zeal. 1

On Palm Sunday, March 20, 1212, Clare attended the Palm Sunday Mass in the cathedral of Assisi. At the moment when the congregation was expected to leave their places and move to the altar to collect palm branches, Clare remained in her place. This attracted the attention of the bishop, who left the altar and walked to Clare. When he reached her, he placed his own palm frond into her hand. This seems to have been a sign to her that she had to act.

That night Clare left her home, accompanied by her aunt, and

went to the Portiuncula, the small chapel which Saint Francis was using for his

recently established Order of Friars Minor.

There he met her, accompanied by his brothers, who carried candles or

torches. By the flickering light Francis

cut the hair of Clare (a traditional act by which women expressed their

renunciation of the world) and gave her a coarse brown habit, like those worn

by the brothers. He also brought her to

the Benedictine convent of San Paolo, where she could receive her initial

training in the religious life.

_Spanish,%20First%20Half%20of%20the%2018th%20Century_Private%20Collection.jpg) |

Verre Eglomisé Pendant with an Image of Saint Clare Spanish, First Half of the 18th Century Private Collection |

Her father and other relatives attempted to remove her from

the convent, but she was adamant about remaining. Sixteen days after her flight from home, she

was joined by her younger sister, Agnes.

Other women, including their mother, Ortolana, also joined them soon

after. Saint Francis gave them the buildings of

the church of San Damiano to be their permanent home. This is the same church that Francis rebuilt

from ruin with his own hands at the beginning of his religious conversion. Clare remained there for the rest of her

life.

Saint Francis initially gave Saint Clare a brief outline of

a Rule of Life lived in total poverty.

Others soon began to meddle, however.

The idea of women religious living such a life was probably of concern

to most people. Women were thought to be

more fragile than men, not suited to such a difficult and potentially unstable

life. Most of the meddling was aimed at

ensuring that the women wouldn’t suffer physical hardships. And, attempts were made by two different

Popes to impose a rule that would allow the women to own property from which

they could be supported. However, Clare

would not agree to this and resisted each time.

Eventually, she triumphed and obtained a rule more closely aligned with

the Franciscan one.

|

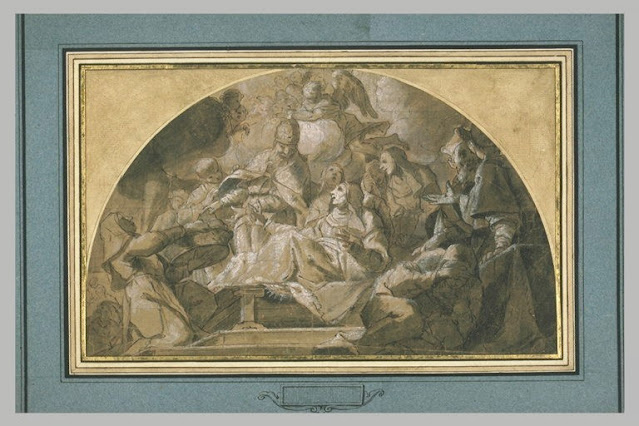

Francesco Solimena, The Ecstasy of Saint Clare Italian, c. 1700-1745 Paris, Musée du Louvre, Département des Arts graphiques |

She and her Sisters remained close to Saint Francis and his Friars during his lifetime. When he died in 1226, his funeral procession made a special stop at San Damiano so that she and her nuns could venerate his body.

During her life Clare remained at San Damiano, gaining a

reputation as an especially pious woman.

She had a very strong devotion to Jesus in the Blessed

Sacrament and her prayers before the monstrance or ciborium are credited with

saving her convent and, indeed, the town of Assisi from invasion. She was a wise abbess to the nuns and was reported to be a miracle worker by the lay population.

|

Francois-Leon Benouville, Saint Clare Meditating French, c. 1840-1859 Beauvais, MUDO, Musée de l'Oise |

In her later years Clare appears to have suffered greatly

from some debilitating illness, perhaps arthritis or something else, which kept

her largely bedridden. She died on

August 11, 1253, at around the age of 60.

Following her death, reports of miracles abounded, and she

was canonized in 1255, only two years after her death. She had initially been buried in her

childhood parish of San Giorgio in Assisi, but after her canonization a new

church, Santa Chiara, was built in her honor.

Her remains were transferred there in 1260. In 1850 her remains were exhumed and in 1872

they were reburied in a new chapel within the same church.

Her feast day is celebrated on August 11th, the

anniversary of her death. Her name,

which means “light” is borne by those named Clare, Claire, Clara, Klara, Chiara,

and related names.

Iconography of Saint Clare

The iconography of Saint Clare seems to cluster around three

main themes. These are portraits of the

saint by herself, scenes from the story of her life and Saint Clare in

association with other saints, frequently but not exclusively Saint Francis.

Saint Clare by herself

These images tend to fall into several categories. They show Saint Clare

As an Abbess

Technically speaking, Clare was the founding Abbess of the

Order of Poor Ladies. As such she is

often shown holding the crozier (staff) that pertains to that position.

,%20c.%201475_London,%20British%20Library_MS%20Harley%202967,%20fol.%20208.jpg) |

| Possibly Workshop of Jacques Pilavaine, Saint Clare From the Breviary of Anthony of Burgundy Flemish (Mons), c. 1475 London, British Library MS Harley 2967, fol. 208 |

|

| Master S, Saint Clare Flemish, c. 1500-1525 London, Trustees of the British Museum |

Holding a Monstrance or Ciborium

Saint Clare had a great devotion to the Blessed Sacrament,

the conserved consecrated Hosts that are the real Body of Christ. This also refers to the event by which she

is reported to have saved her convent and the town of Assisi from invasion by

the forces of the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II during his attempt to extend

his power in Central Italy. This is described in more detail below.

,%20c.%201415-1425_New%20%20York,%20Pierpont%20Morgan%20Library_MS%20M%20374,%20fol.%20136v.jpg) |

| Gold Scrolls Group, Saint Clare of Assisi From a Missal Flemish (Bruges), c. 1415-1425 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M 374, fol. 136v |

,%20c.%201450-1475_Paris,%20Bnf_MS%20Francais%20298,%20fol.%20109r.jpg) |

| Saint Clare of Assisi From a Fleur des histoires by Jean Mansel Flemish (Bruges), c. 1450-1475 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 298, fol. 109r |

|

| Israhel van Meckenem, Saint Clare German, c. 1465-1475 London, Trustees of the British Museum |

|

| Saint Clare of Assisi German, c. 1470-1480 Washington, National Gallery of Art |

,%20c.%201500_London,%20British%20Library_MS%20Yates%20Thompson%2029,%20fol.%2062r.jpg) |

| Amico Aspertini, Saint Clare From the Hours of Bonaparte Ghislieri Italian (Bologna), c. 1500 London, British Library MS Yates Thompson 29, fol. 62r |

|

| Circle of Juan de Borgonya, Saint Clare Spanish, c. 1500-1533 Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado |

|

| Saint Clare of Assisi Italian, 16th Century Rieti, Monastery of Fonte Colombo, Cappella della Maddalena |

|

| Giacomo Cavedone, Saint Clare Kneeling and Holding a Monatrance Italian, First Half of 17th Century London, Victoria and Albert Museum |

|

| Jean Leclerc IV, Saint Clare with a quotation from the Book of Wisdom, Verse 4 French, Late 16th/Early 17th Century London, Trustees of the British Museum |

|

Saint Clare Holding the Monstrance Italian, 17th Century Paris, Musée du Louvre, Département des Arts graphiques |

|

| Antoine Sallaert, Saint Clare Flemish, c. 1609-1650 London, Trustees of the British Museum |

|

| Michiel Snyders, Saint Clare Flemish, 1613 London, Trustees of the British Museum |

|

| Michel Lasne after Claude Vignon, Sancta Clara Exemplary Nun French, c. 1621-1667 London, Trustees of the British Museum |

,%20The%20Bowes%20Museum.jpg) |

| Circle of Alonso del Arco, Saint Clare Holding a Monstrance Spanish, Second Half of the 17th Century Barnard Castle, Co. Durham (UK), The Bowes Museum |

_Spanish,%20c.%201652_Madrid,%20Museo%20Nacional%20del%20Prado.jpg) |

| Alonso Cano, Saint Clare Spanish, c. 1652 Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado |

|

Saint Clare Italian, 17th Century Nardo, Church of Sant'Antonio |

,%20c.%201731-1751_Sevres,%20Manufacture%20et%20musee%20nationaux.jpg) | ||

Saint Clare Porcelain Plaque French (Sevres), c. 1731-1751 Sevres, Manufacture et musée nationaux

|

With a Book

The book is a reference to the Gospels, which Saints Francis

and Clare took as their guide for life.

|

| Lippo Memmi, Saint Clare Part of an Altarpiece for the Church of San Francesco in San Gimimgnano Italian, c. 1330 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

|

| Saint Clare French, c. 1400 Paris, Musée de Cluny, Musée national du Moyen Age |

,%20c.%201445-1460+Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Latin%209473,%20fol.%20186v.jpg) |

| Saint Clare of Assisi From the Hours of Louis of Savoy French (Savoy), c. 1445-1460 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 9473, fol. 186v |

,%20c.%201450-1450_London,%20British%20Library_MS%20Additional%2071119F.jpg) |

| Master of the Budapest Antiphonary, Saint Clare Cutting from a Service Book Italian (Lombardy), c. 1450-1450 London, British Library MS Additional 71119 |

|

| Francesco del Cossa, Saint Clare Italian, c. 1470-1472 Madrid, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museo Nacional |

|

| Luca Signorelli, Saint Clare of Assissi Italian, c. 1515-1520 Altenburg, Lindenau-Museum |

Holding a Crucifix

Saint Clare also had a great devotion to the Passion of

Christ and is sometimes shown holding a crucifix.

|

| Vittore Crivelli, Saint Clare Italian, 1491 Private Collection |

|

School of Marco da Oggiano, Saint Clare Italian, c. 1515-1519 Paris, Musée du Louvre |

Holding a Palm Branch

This is a reference to the first “official” notice of Saint

Clare, when the Bishop of Assisi gave her his own palm frond on the day before

her dramatic flight from home.

|

School of Lorenzo d'Alessandro, Saint Clare Italian, 15th Century Avignon, Musée du Petit Palais |

Holding a Lily

|

| Giotto, Saint Clare Italian, c. 1325 Florence, Church of Santa Croce, Bardi Chapel |

Scenes from the Life of Saint Clare

Most of the images depicting scenes from the life of Saint

Clare are based in events that really happened.

However, some of these scenes are interpreted in ways that make them

seem more like legends. This is not

uncommon in the lives of saints prior to the era of the Counter-Reformation,

which lay many centuries in the future at the time in which Saint Clare lived. Her life was described by the contemporary Franciscan

Friar Thomas of Celano, who was also the first biographer of Saint

Francis. Of course, at the period during

which they all lived, the biography of a saint or holy person was more properly

termed hagiography and tends to emphasize deeds that include miracles and

visions, things not currently considered proper for a true biography.

Presentation of the Palm by the Bishop of Assisi

On Palm Sunday, at Mass in the cathedral, Clare remained in

her place when all the other young ladies of Assisi flocked to the altar to

collect palms (perhaps for a procession).

This is often ascribed to modesty and sometimes to prayerful

distraction. In any case, it drew the

attention of the bishop of Assisi who descended from the altar and approached

Clare, handing her his own palm. This

seems to have been regarded by Clare and her later interpreters as a sign that

she had been chosen for a religious life.

|

| The Bishop of Assisi Giving a Palm to Saint Clare German, c. 1360 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Cloisters Collection |

|

| The Bishop of Assisi Presenting His Palm Branch to Saint Clare Austrian, c. 1465-1475 Bamberg, Staatsgalerie |

|

| After Paolo Veronese, Saint Clare Receiving the Palm Italian, c. 1550-1560 Hillsborough Castle, Royal Collection Trust |

Cutting of Clare’s Hair and Giving of the Habit

On the night of Palm Sunday, following the incident in the

cathedral, Clare left her parents’ home and, accompanied by her aunt, went to

the chapel of the Portiuncula where Saint Francis and his brothers were waiting

for her with candles and torches. There Francis

cut her hair, gave her a coarse brown habit and black veil. These were symbolic of her renunciation of

the world. He then brought her to the

convent of the Benedictine nuns, where she was to learn the details of life as

a religious woman.

,%20Princeton%20University%20Art%20Museum.jpg) |

| Saint Francis Cutting the Hair of Saint Clare Cutting from a Choir Book Italian, c. 1375 Princeton (NJ), Princeton University Art Museum |

,%20c.%201500_London,%20V&A.jpg) |

| Attributed to Domenico Morone, Saint Francis Clothing Saint Clare in the Franciscan Habit Cutting from a Choir Book Italian (Verona), c. 1500 London, Victoria and Albert Museum |

|

| Saint Francis Cutting Saint Clare's Hair Italian, 16th Century London, Trustees of the British Museum |

|

Fra Semplice Da Verona, Saint Francis Cutting the Hair of Saint Clare Italian, First Half of 17th Century Grenoble, Musée de Grenoble |

|

Florentine School, Saint Francis Investing Saint Clare with the Franciscan Habit Italian, First Half of 17th Century Caen, Musée des Beaux-Arts |

|

| Giovanni Domenico Cappellino, Saint Clare Welcomed at the Altar by Saint Francis after Taking Her Vows Italian, First Half of 17th Century Private Collection |

|

| Antonio Carnicero, Saint Francis Cutting Clare of Assisi's Hair Spanish, c. 1787-1789 Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado |

Receiving the Rule

Saint Francis presented a brief Rule of Life to Clare and

the young women who soon joined her, including her younger sister, now Saint

Agnes of Assisi.

|

Fra Filippo Lippi, The Enthroned Saint Francis Gives Saint Clare the Rule of the Order Italian, c. 1465-1470 Berlin, Gemäldegalerie der Staatliche Museen zu Berlin |

The Death of Saint Francis

When I was a child there was a Hollywood interpretation of

the life of Saint Francis, called Saint Francis of Assisi. The movie starred Bradford Dillman as Francis

and Dolores Hart as Clare. The film, which is a fairly standard Hollywood

biopic, without the weird and outright silly interpretations of some other

films, is notable primarily because the leading lady, Dolores Hart, left

Hollywood behind two years later and became a cloistered Benedictine nun at the

Abbey of Regina Laudis in Connecticut, where she has remained all these

years. The film depicts Francis and

Clare as being about the same age. In

reality, Clare was several years younger.

When in 1226 Saint Francis died at the Portiuncula on the

outskirts of Assisi, his body was brought to Assisi in a funeral

procession. It made several stops along

the way (for more on this please see my article on the Death of Saint Francis). One of the stops was made at

San Damiano so that Clare and her nuns would be able to venerate the body of

their founder and model. The scene has

frequently been imagined by artists and was one of the most memorable scenes in the 1960 film.

|

| Giotto, Legend of Saint Francis, Saint Clare and Her Sisters Mourning Saint Francis Italian, 1300 Assisi, Church of San Francesco, Upper Church |

,%2014th-15th%20Century_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Francais%202093,%20fol.%2084v.jpg) |

| Saint Clare Viewing the Body of Saint Francis From a Vie de Saint Francois French (Northern), 14th-15th Century Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 2093, fol. 84v |

|

+Leon Benouville, Saint Clare Receiving the Body of Saint Francis of Assisi French, 1858 Chantilly, Musée Conde |

|

| Benito Mercade y Fabregas, Transitus of Saint Francis of Assisi Spanish, 1866 Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado |

|

| Ludovico Grillotti, Death of Saint Francis of Assisi Italian, 1899 Subiaco, Church of San Francesco |

Saint Clare, Defender of Assisi

One story from the life of Saint Clare, which sounds a

little improbable to modern minds, seems to have a very solid basis in

historical fact. The 12th and

13th centuries were a terrible period in the Italian peninsula,

leading to several more centuries of civil unrest and invasion. During that time almost the whole of Italy

was swept up in a series of bloody wars between the forces of the Holy Roman

Emperor and the contemporary Popes. The opposing forces adopted the names of

Guelph (supporters of the Popes) and Ghibelline (supporters of the emperor). Their conflict was the world in which the

poet Dante grew up and was himself involved.

These experiences and the views they represent form the background for Dante’s

great poem, The Divine Comedy.

During one of these wars, Emperor Frederick II sent his troops into

the region of Umbria (between Tuscany and Lazio) in an intended attack on

Rome. Their path took them through

Assisi twice. On the first occasion some

of the troops (traditionally said to be Saracen mercenaries from Frederick's southern lands in Sicily) managed to breach

the outer walls of the isolated convent of San Damiano, outside the city walls

of Assisi. Needless to say, the presence

of soldiers, especially if they were non-Christian ones, inside the walls of a

convent was terrifying for the nuns.

Saint Clare, who was in bed when the assault began, got up and went to

the chapel of the convent where the Blessed Sacrament was reserved for

adoration. She took the receptacle in

which the Eucharist was reserved. Some

accounts say that it was in a ciborium (closed vessel), while others call it a

monstrance (vessel in which a reserved Host is visible). Some pictures represent it as something in

between, a closed but transparent vessel.

She carried this to a window within the inner cloister building and held

it aloft. According to the reports the

sight of this terrified the attackers and they withdrew.

|

| Isidoro Arredondo, Saint Clare Driving Away the Infidels with the Eucharist Spanish, 1693 Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado |

|

| Saint Clare Defending Her Convent Italian, 18th Century Paray-le-Monial, Musée Eucharistique du Hieron |

|

| Ludovico Grillotti, Saint Clare Expels the Saracens from the Convent of San Damiano by Raising the Monstrance Italian, 1899 Subiaco, Church of San Francesco, Cloister |

About one year later the Imperial forces were once more attempting to attack Rome and this time laid siege to the walled town of Assisi but did not disturb the nuns at San Damiano. On this occasion, Saint Clare called all her nuns to the chapel and together they prayed for the delivery of the town on their knees in front of the exposed Blessed Sacrament. Their prayers were heard and the siege was lifted, the town was spared. The people of Assisi considered Clare to be their protector through her prayers.

|

| Cavaliere d'Arpino, Saint Clare at the Siege of Assisi Italian, First Half of the 17th Century St. Petersburg, State Hermitage Museum |

|

| Hieronymous Wierix, Saint Clare Praying Before the Eucharist Flemish, 1619 London, Trustees of the British Museum |

|

Saint Clare and Her Nuns Praying for the Deliverance of Assisi French, c. 1630-1640 Paris, Musée du Louvre The group of nuns includes her blood sister, Saint Agnes of Assisi. |

Death of Saint Clare

This is the event of her life in which the historical and

the supernatural mix most profoundly.

Following her defense of the town of Assisi in 1241 and 1242 Saint Clare

continued to live her life of piety and radical poverty. Though plagued by ill health she continued to

lead her sisters, which now included not only her sister Agnes, but her mother

Ortolana and other family members. She

fought tenaciously against two Popes and their representatives to maintain the

adherence of her Rule to the ideals of total poverty espoused by Saint Francis

and given to her during the dramatic early days of her flight from the

world. The number of her sisters grew

and convents of Poor Ladies, becoming known as Poor Clares, were being

established throughout Italy and into the rest of Europe.

In 1253 it became obvious that Clare was dying. During her last days she was visited by some

of the remaining original brothers of Saint Francis, by Cardinals and by the

Pope himself. In addition, there is a

legend that on her last day she was also visited by a heavenly party, composed

of female saints, and led by the Blessed Virgin Mary herself. The supernatural party was described as a

group of women, dressed in white and with golden crowns on their heads, who

appeared in the room in which she lay.

Their leader, the Virgin herself, approached the dying woman along with

two others who held in their hands a beautiful cloak. The Blessed Virgin wrapped Clare in the cloak

and then they disappeared. Clare died

later that day.

|

| Master of Heiligenkreuz, The Death of Saint Clare Austrian, 1410 Washington, National Gallery of Art |

|

Attributed to Luca Giordano, The Death of Saint Clare Italian, Second Half of 17th Century Clamecy, Musée d'Art et d'Histoire Romain Rolland |

|

| Bartolome Esteban Murillo, The Death of Saint Clare Spanish, c. 1650-1682 St. Petersburg, State Hermitage Museum |

|

| Giacomo Giogetti, The Virgin Mary at the Deathbed of Saint Clare Italian, 1657 Assisi, Pinacoteca Comunale |

|

Attributed to Antonio Nasini, The Death of Saint Clare Italian, c. 1700 Paris, Musée du Louvre, Département des Arts Graphiques |

Her funeral was splendid. The Pope, who had visited her shortly before, came back to Assisi to celebrate the funeral. A long and splendid procession brought her body from San Damiano to a grave at her childhood church of San Giorgio, where Saint Francis had also been buried at this death.

Within two years the Pope was back in Assisi to preside over

her canonization and reburial in the new church named for her, Santa Chiara,

where her body remains to this day.

Clare as a Saint Among Saints

So far, we have looked at Saint Clare’s imagery as a solitary saint and as the subject of paintings about her life. However, there are other images of Saint Clare that have developed over time. These are images of Clare in company with others. This type of image can be called a

Sacra

Conversazione (Holy Conversation)

|

| Niccolo di Liberatore (called l'Alunno), The Madonna and Child with Saints Francis, John the Baptist, Jerome and Clare Italian, c. 1465-1470 Rome, Palazzo Barberini |

|

Alvise Vivarini, The Madonna and Child with Saints Catherine of Alexandria, Clare and John the Baptist Italian, c. 1465 Berlin, Gemäldegalerie der Staatliche Museen zu Berlin |

|

| Domenico Ghirlandaio, The Enthroned Madonna and Child with Saints Clare, Paul, Francis and Catherine of Alexandria Italian, c. 1480-1500 Berlin, Gemäldegalerie der Staatliche Museen zu Berlin |

|

| Baldassare Manara, Dish with Saints Peter, Clare and Barbara (?) Italian, c. 1535 Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum |

However, not all images of Clare with others fall into this distinctive category. There are other ways in which Clare appears with others.

These images place Saint Clare in the context of a series of

Franciscan Saints, both from her own time and later periods.

|

| Simone Martini, Saints Clare and Elizabeth of Hungary Italian, c. 1320-1325 Assisi, Church of San Francesco, Lower Church, Chapel of Saint Martin |

|

| Giovanni di Paolo, Saints Clare and Elizabeth of Hungary Italian, c. 1445 Private Collection |

|

| Probably by the Ghent Gradual Master, Saints Francis, Clare and Bernardino of Siena From a Prayer Book Flemish (Ghent or Tournai), c. 1450 London, British Library MS Stowe 23, fol. 62r |

|

| Master of the Glorification of Mary, Saints Clare, Bernardino, Bonaventure and Francis German, c. 1480 Cologne, Walraf-Richartz-Museum & Fondation Corboud |

|

| Garofalo, The Virgin and Child Enthroned with Saints William of Aquitaine, Clare, Anthony of Padua and Francis Italian, 1517 London, National Gallery |

|

| Moretto da Brescia, The Madonna and Child with Saints Catherine of Alexandria, Clare, Jerome, Joseph, Bernardino, Francis and Nicholas of Bari Italian, c. 1540-1545 London, National Gallery |

|

| Giuseppe Di Gardo, The Madonna in Glory with Saints Bonaventure, Bernardino of Siena and Clare of Assisi Italian, c. 1768-1800 Castelbuono, Church of Saint Francis |

|

| Anna Jameson, Six Franciscan Saints: Bonaventure, Anthony of Padua, Catherine of Alexandria, Clare, Bernardino and Louis of Toulouse Anglo-Irish, 19th Century London, Wellcome Collection |

Clare and Francis as a Saintly Pair

Saints Clare and Francis are often depicted together, either

just the two of them or in a group of other saints. As founders of their respective portions of

the Franciscan family they appear as a kind of saintly couple.

|

| Giotto, Saint Francis and Saint Clare Italian, c. 1278-1300 Assisi, Church of San Francesco, Upper Church |

|

| Attributed to Ugolino da Siena, The Crucifixion with Saints Clare and Francis of Assisi_\ Italian, c. 1315-1320 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

,%20Harvard%20Art%20Museums-Fogg%20Museum.jpg) |

| Pietro Lorenzetti, The Crucifixion with Saints Clare and Francis Italian, c. 1320 Cambridge (MA), Harvard Art Museums-Fogg Museum |

|

| Masters of Hug Janzoon van Woerden, The Crucifixion with Saints Francis and Clare From a Book of Hours Dutch (Northern Holland), c. 1450-1475 The Hague, Koninklijk Bibliotheek MS KB 129 F 4, fol.48v-49r |

|

| Israhel van Meckenem, Saints Francis and Clare Hand-colored Engraving from a Prayer Book German, c. 1480-1490 London, Trustees of the British Museum |

|

| Pompeo Cocchi, The Madonna and Child with Saints Francis, Clare, Louis of Toulouse and Proculus Italian, c. 1490-1552 Terni, Pinacoteca Comunale di Terni |

|

| The Madonna and Child with Saints Francis,Catherine of Siena and Clare Italian, 16th Century London, Royal Collection Trust |

|

| Lorenzo Lotto, The Madonna and Child with Saints Paul, Peter, Clare and Francis Italian, c. 1506 Edinburgh, National Gallery of Scotland |

|

| Giovanni Battista Cima da Congegliano, The Madonna and Child with Saints Francis and Clare Italian, c. 1510 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

|

| Circle of the Carracci, The Virgin and Child with Saints Clare and Francis Italian, c. 1580-1590 Chicago, Art Institute |

|

| Durante Alberti, The Enthroned Madonn and Child with Saints Jerome, Francis and Clare Italian, c. 1599 Assisi, Pinacoteca Comunale |

|

| Hieronymus Wierix, Christ and the Virgin Adored by Saints Francis and Clare Flemish, Before 1619 London, Trustees of the British Museum |

|

| Ivory Plaque of Saints Clare and Francis South Asian, 17th Century London, Trustees of the British Museum |

|

Ludovico Carracci, The Madonna and Child with Saints Francis and Clare Italian, c. 1600-1619 Paris, Musée du Louvre |

|

| Antonio Cicignani, The Immaculate Conception with Saints Anthony, Francis, Clare and Mary Magdalene Italian, c. 1601-1615 Assisi, Pinacoteca Comunale |

|

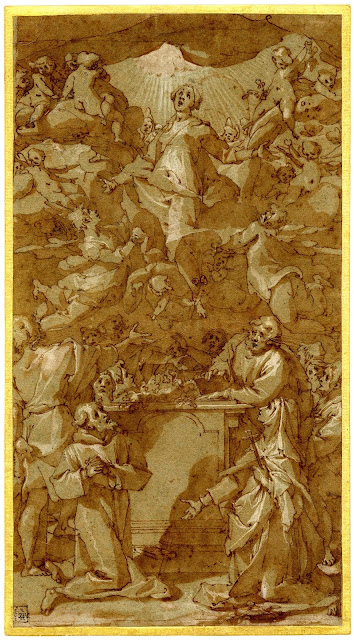

| Andrea Boscoli, The Assumption of the Virgin with Saints Francis and Clare Italian, c. 1605 London, Trustees of the British Museum |

|

| Pieter de Jode II after Gerard Segers, The Infant Christ Adored by Saints Francis and Clare Flemish, c. 1640-1674 London, Trustees of the British Museum |

|

| Giovanni Battista Gaulli, The Immaculate Conception with Saints Francis and Clare Italian, c. 1680-1686 London, Royal Collection Trust |

|

| Attributed to Giovanni Antonio Burrini, Saints Francis of Paula, Francis of Assisi, Catherine of Alexandria and Clare of Assisi Italian, c. 1700 London, Royal Collection Trust |

|

Maurice Denis, Saint Francis Visiting Saint Clare and Her Sisters Illustration for the Fioretti, the Little Flowers of Saint Francis French, 1911 Paris, Musée du Louvre, Département des Arts graphiques |

The Vision of Saint Clare

Clare is sometimes shown in what can be

called the Vision of Saint Clare, in which she is seen as a visitor to the home

of the Holy Family, in adoration of the Christ Child or as the recipient of his

attention.

|

| Federico Zuccaro, The Holy Family with Saints Catherine of Alexandria and Clare of Assisi Italian, c. 1580-1609 London, Trustees of the British Museum |

|

| Guido Reni, The Holy Family with Saint Clare Italian, c. 1590-1600 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

|

| Guercino, The Vision of Saint Clare Italian, c. 1615-1621 St. Petersburg, State Hermitage Museum |

|

| Gerard Seghers, Saint Clare Adoring the Child Jesus Flemish, c. 1630-1650 Antwerp, Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten |

|

| Jean Louis Roullet after Annibale Carracci, The Virgin and Child with Saint Clare French, Late 17th Century Philadelphia, Museum of Art |

Among a Group of Other Saints

One of the greatest representations of Saint Clare can be

found in the design for a tapestry prepared by Peter Paul Rubens for his

patroness, the Princess Isabella Clara Eugenia, Infanta of Spain, and

Archduchess of Brabant. Princess

Isabella Clara Eugenia was the daughter of King Philip II of Spain and the wife

of Archduke Albert of Austria, Duke of Brabant.

With her husband, and later as a widow, she governed the Netherlands

(comprising today’s Holland, Belgium and Luxembourg) on behalf of her father

(and later of her half-brother, Philip III).

Saint Clare was her patron saint and, in her widowhood, the Princess

became a lay member of the Poor Clares.

Saint Clare had a great devotion to the Holy Eucharist, as

is evident in the story of her defense of her convent and in the iconography in

which she is shown holding a monstrance or ciborium. Her spiritual daughters maintained this

devotion through the centuries following her death. In this tapestry series, known as the Triumph

of the Eucharist, she is shown particular honor. The series is comprised of twenty designs and

was commissioned by the Archduchess in 1628 as a gift to the convent of Unshod

Poor Clares in Madrid, known as the Descalzes Reales. The designs were woven in Flanders between

1628 and 1633, when they began arriving at their final home.

The series is conceived as if composed of tableaux outlining the history of the Eucharist in the Old and New Testament and in church history. One of the most important tapestries of the series is the one known as the Defenders of the Eucharist. This is comprised of a procession of saints who had a particular devotion to the Eucharist or who contributed to the Church’s understanding of it. This panel includes Popes and theologians who wrote about the Eucharist. These include such great men as Saint Ambrose, Saint Augustine, Saint Gregory the Great, Saint Thomas Aquinas, Saint Norbert and Saint Jerome. And in the very center of the composition is one woman, Saint Clare of Assisi, holding aloft a monstrance with the Host. It is she and Saint Thomas Aquinas, who wrote the liturgical prayers for the feast of Corpus Christi, who are most active and who dominate the composition as well as form its center. The other saints seem to look to them for guidance.2

Not every composition in which Saint Clare appears with other saints is of such great importance, however. In most cases she appears either as a member of a group of

Other female saints

|

| Neri di Bicci, Saints Agnes of Rome and Clare of Assisi Italian, Mid-1470s Philadelphia, Museum of Art |

|

| Alvise Vivarini, Saint Clare and a Female Martyr Saint Italian, c. 1485 Venice, Galleria dell'Accademia |

|

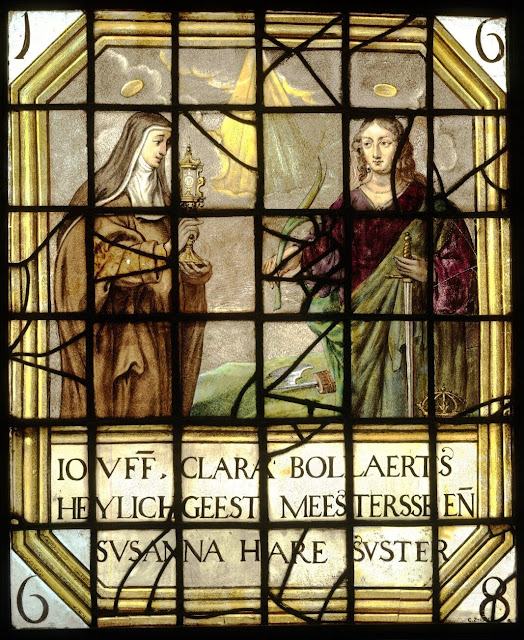

| Saints Clare and Susanna Flemish, 1668 London, Victoria and Albert Museum |

Random Groups of Saints

Or in what appears to be a random group of saints, probably determined by the patron of the work of art

|

| Simone Martini, Christ Delivering the Keys to Saint Peter, Saints Christopher, Mary Magdalen, Clare and Elizabeth of Hungary Italian, c. 1325 London, Victoria and Albert Museum |

|

| Lippo Memmi, The Madonna and Child with Saints and Angels Italian, c. 1350 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art Saint Clare appears in the predella, second from the left. |

|

| Altarpiece of the Adoration of the Magi with Saints Adrian and Clare Flemish, c. 1515-1520 Antwerp, Snijders-Rockox Huis Museum |

|

| Glass Roundel with Saints Jodocus and Clare of Assisi Flemish, c. 1520-1530 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Cloisters Collection |

Saint Clare in the Court of Heaven

Or as a member of the Court of Heaven, joining a group of other saints in adoration of God or of the Virgin and Child in a heavenly setting.

|

| Caterino Veneziano, The Madonna and Child with the Crucifixion and Saints Italian, c. 1380-1389 Baltimore, The Walters Art Museum |

|

| The Coronation of the Virgin Spanish, c. After 1521 Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado |

|

| Moretto da Bressia (Alessandro Bonvicino), The Assumption of the Virgin with Saints Mark and Jerome, Catherine of Alexandria and Clare Italian, c. 1529 Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera |

|

| Peter Paul Rubens, The Holy Family Surrounded by Saints Flemish, c. 1630 Madrid, Museo National del Prado |

Patroness

In addition, Saint Clare appears as a patron saint to those still struggling to get to heaven. Thus, she appears standing behind individuals or groups as she presents them for divine approval.

|

| Hans Memling, Outer Wings of the Saint John Altarpiece, with Saints James the Greater, Anthony Abbott, Agnes of Rome and Clare of Assisi Flemish, c. 1474-1479 Bruges, Memlingmuseum, Sint-Janshospitaal |

|

Joos van Cleve, The Lamentation Altarpiece, with Donors and Saints Nicholas of Tolentine and Clare of Assisi Flemish, c. 1520-1525 Paris, Musée du Louvre |

This then, is the iconography of Saint Clare, one of the most important women of the Middle Ages, whose daughters are still at work in the world today, often in surprising ways. One of them, Mother Angelica, was the plucky founder of Eternal Word Television (EWTN) which has become a leading force in evangelization in the US and around the world. Whatever your opinion of the network may be you will grant that it was undertaken very much in the spirit of Saint Clare, who resisted the efforts of Popes and other outsiders in her determination to follow the Rule of Saint Francis.

+Indicates an updated image.

*Indicates a new image.

1. For sources and commentary on the life of Saint Clare see

the following:

The Golden Legend or Lives of the Saints.

Compiled by Jacobus de Voragine, Archbishop of Genoa, 1275. First Edition Published 1470. Englished by

William Caxton, First Edition 1483, Edited by F.S. Ellis, Temple Classics, 1900

(Reprinted 1922, 1931.) © The Internet

Medieval Sourcebook is part of the Internet History Sourcebooks Project, https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/basis/goldenlegend/GoldenLegend-Volume6.asp#Clare

The Life of Saint Clare ascribed to Thomas of Celano of

the Order of Friars Minor (AD 1255-1261) translated and edited from the

earliest MSS by Fr. Paschal Robinson of the same Order: with an Appendix

containing the Rule of Saint Clare, The Dolphin Press, Philadelphia,

1910. https://archive.org/details/lifesaintclarea00robigoog/page/n240/mode/2up

Robinson, Paschal. "St. Clare of Assisi." The

Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908.

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04004a.htm

Much more up to date sources for documents and commentary

can be found at Feminae:

Medieval Women and Gender Index (http://inpress.lib.uiowa.edu/feminae/QuickSearch.aspx) Search for Clare of Assisi, Saint. There are 45 books and articles that are

linked from the search results page, many of them focusing on the battles

between Clare and church officials about the inclusion of radical poverty in

the Rule.

In addition for the specific connection between this work and its patroness, Princess Isabella Clara Eugenia, see Libby, Alexandra. “The Solomonic Ambitions of Isabel Clara Eugenia in Rubens’s The Triumph of the Eucharist Tapestry Series” in Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art, Vol. 7, Issue 2, Summer 2015. https://jhna.org/articles/solomonic-ambitions-isabel-clara-eugenia-rubens-triumph-of-the-eucharist-tapestry-series/

,%20c.%201260-1275_New%20York,%20Pierpont%20Morgan%20Library_MS%20M%20880,%20fol.%201r.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment