|

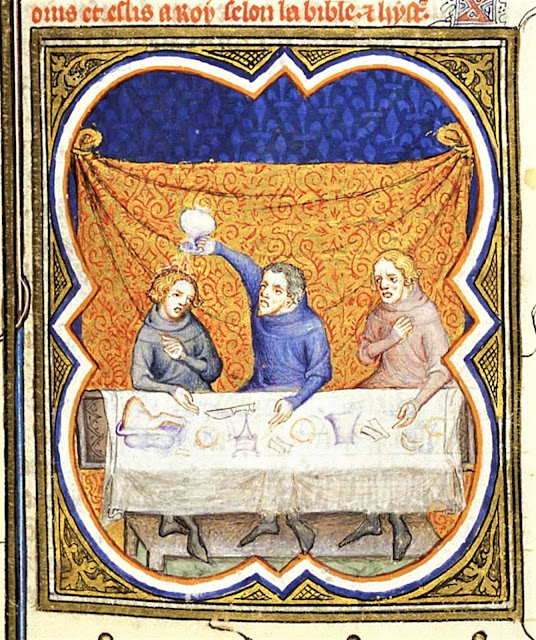

| Jean Fouquet, David Anointed by Samuel From Le Livre de Jehan Bocace des cas des nobles hommes et femmes French, 1458 Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek MS Cod. gall. 6, fol. 46v |

"How long will you grieve for Saul,

whom I have rejected as king of

Israel?

Fill your horn with oil, and be

on your way.

I am sending you to Jesse of

Bethlehem,

for I have chosen my king from

among his sons."

But Samuel replied:

"How can I go?

Saul will hear of it and kill

me."

To this the LORD answered:

"Take a heifer along and

say,

'I have come to sacrifice to the

LORD.'

Invite Jesse to the sacrifice,

and I myself will tell you what to do;

you are to anoint for me the one

I point out to you."

Samuel did as the LORD had

commanded him.

When he entered Bethlehem,

the elders of the city came

trembling to meet him and inquired,

"Is your visit peaceful, O

seer?"

He replied:

"Yes! I have come to

sacrifice to the LORD.

So cleanse yourselves and join me

today for the banquet."

He also had Jesse and his sons

cleanse themselves

and invited them to the

sacrifice.

As they came, he looked at Eliab

and thought,

"Surely the LORD's anointed

is here before him."

But the LORD said to Samuel:

"Do not judge from his

appearance or from his lofty stature,

because I have rejected him.

Not as man sees does God see,

because he sees the appearance

but the LORD looks into the

heart."

Then Jesse called Abinadab and

presented him before Samuel,

who said, "The LORD has not

chosen him."

Next Jesse presented Shammah, but

Samuel said,

"The LORD has not chosen

this one either."

In the same way Jesse presented

seven sons before Samuel,

but Samuel said to Jesse,

"The LORD has not chosen any

one of these."

Then Samuel asked Jesse,

"Are these all the sons you

have?"

Jesse replied,

"There is still the

youngest, who is tending the sheep."

Samuel said to Jesse,

"Send for him;

we will not begin the sacrificial

banquet until he arrives here."

Jesse sent and had the young man

brought to them.

He was ruddy, a youth handsome to

behold

and making a splendid appearance.

The LORD said,

"There–anoint him, for this

is he!"

Then Samuel, with the horn of oil

in hand,

anointed him in the midst of his

brothers;

and from that day on, the Spirit

of the LORD rushed upon David.

When Samuel took his

leave, he went to Ramah.

1 Samuel 16:1-13 (Reading form January 16, 2018)

The majority of Catholics are at least marginally aware that

the liturgical calendar currently followed by the church divides the year up

into several “seasons”, specifically Advent, Christmas, Lent, the Pascal

Triduum, Easter and something rather vaguely called “Ordinary Time”. These “seasons” relate to both the seasons of

the year and the civil calendar year only tangentially. Thus, Christmas comes on a fixed date at the

end of December and lasts into January, while Lent begins on a different date in

the winter and concludes in early Spring with the Feast of Easter, which is

determined not by a fixed date, but by the spring equinox.

Some may be puzzled by the way in which “Ordinary Time”

seems to be chopped up into segments, with the biggest one being the period

from the Feast of Corpus Christi, which follows close upon the Feast of

Pentecost, running roughly from mid-June until the ultimate or penultimate

Sunday in November when the Feast of Christ the King ends the liturgical

year. A new year begins the following

Sunday with the first Sunday of Advent. However, there are a few weeks of Ordinary

Time wedged in between Christmas and Ash Wednesday, the first day of Lent. 1

|

| Nicolaes Maes, Samuel Anointing David Dutch, c. 1670 Private Collection |

It wasn’t always like this. Prior to the revision of the General Roman Calendar in 1969 there was a period known as “Weeks after Epiphany”, the number of which would vary with the date of Ash Wednesday, being smaller or greater depending on whether Easter (and therefore Lent) was early or late. There were also three Sundays prior to the beginning of Lent which took their names from the number of days by which they preceded Easter. There was Septuagesima Sunday (70 days), Sexigesima Sunday (60 days) and Quinquagesima (50 days).

I was a teenager at the time of the post-Vatican II changes in the Church calendar and, like most teenagers, occupied by the studies and social activities appropriate to my age. And, again like most teenagers and also most adults, the thing that seemed most striking at the time was, not the change in the calendar but the change in the language. All through my teens and very early 20s the changes were recurrent, with the Mass being translated in bits, first in language closely aligned to the underlying Latin prayers and then to language of “dynamic equivalence”, which was more conversational sounding. By my mid-20s the substitution was complete, with not only changes to the Mass but to the administration of the other Sacraments as well.

|

| Caspar Luyken, Samuel Anointing David Dutch, 1712 Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum |

One was

also aware of some novelties appearing, such as the handshake of peace, which

was an introduction to the laity of a more “contemporary” action to echo the formal

clerical kiss of peace. What one was not

so aware of was the reorganization brought about by lumping the Sundays between

Epiphany and Lent and the period between Corpus Christi and Advent under the

same generic header of “Ordinary Time”.

At the same time, of course, many saints whose feast days

had been celebrated universally, sometimes for centuries, were “demoted”. Their feast days were reduced to celebration

only within a diocese or religious community which was particularly tied to

them, or to one or two memorial prayers in the universal Church calendar. Of course, they were frequently replaced in

the universal calendar by more recent saints, but all too often the weekdays

became simply “Weekdays”.

I bring this up because reordering the calendar was also done in order to expand the amount of Scripture read in the course of the year. Prior to the revision, the number of texts, while extensive, was unvarying. The same readings, associated with the day of the season or with a particular saint, were read year after year. With the revision, the number of texts was dramatically increased, so that now nearly all of Scripture is read at Mass, following two specific cycles.

The Sunday cycle of readings is a three-year cycle, which

means that the Gospels read at most Sunday Masses during a single year are drawn

from the three Synoptic Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke. The Gospel of John is also read, but it

interweaves with the cycle for specific days throughout the year. The years are designated by a simple letter

code of A, B and C. Some Sundays and

major feasts have specific Gospels attached to them, which are used across this

three-year cycle, being read in all three years.

On weekdays, the readings follow a two-year cycle, which

uses a numbered code: Years 1 and 2. In

this way, most of the Bible is read, including both Old and New Testaments,

Acts of the Apostles, the Epistles and Revelation over the course of a Sunday

cycle (3 years) and a numbered cycle (2 years), which are constantly

rotating. 1

I am mentioning all this because it is interesting to note that, as I have been working on this blog at this point for nearly ten years (!) I have been presenting essays on the art inspired by the Bible through three of the Sunday cycles and five of the two-year weekday cycles. And, because of that, there are recurring themes and stories that I have worked on (and will continue to work on). You may note that I frequently point toward commentary I have done in previous years over in the right column alongside the current essays. It recently struck me that, as I prepared for today’s essay on Samuel’s discovery and anointing of the young David, I had written about David in what seemed to me to be the very recent past. Looking through the list of posts I found that it was almost exactly two years ago, January 20, 2016, that I had written about David and Goliath. And this is why I digressed above into the consideration of the cycles of liturgical readings, for the reading about David and Goliath will recur this year on January 17, 2018.

Compared to the story of David and Goliath, however, images of the story of how Samuel was led to discover David among the sons of Jesse are not as generously distributed. It does begin very early, however.

One of the earliest

depictions we have comes from the Jewish Synagogue excavated in the town of

Dura-Europos in Syria in 1932 and later.

The fact that the Synagogue contained several large painted narrative

scenes came as a surprise to everyone, since it had been assumed that Judaism

had a complete ban on the painting of images.

It is now understood that it is a more sophisticated and narrow prohibition on painting (or carving) an image of God and that prior Jewish images may lie

behind some early Christian paintings.

|

| Samuel Anoints David Syrian, c. 240-245 Dura Europos (Syria), Synagogue |

The picture from Dura-Europos, dated the middle of the third

century AD, depicts Samuel, clad in a tunic and toga resembling that of a Roman

senator to indicate his standing, holds an anointing horn over the head of

David, while some of David’s brothers look on and indicate their acceptance of

his new position.

It is difficult to tell how much material we may be missing

from the turbulent centuries of the barbarian invasions and slow retreat of the

Roman Empire from both western Europe and their lands in Asia Minor and the

territories of Palestine and Syria.

However, in the first half of the seventh century a splendid set of

decorative silver plates was made in Constantinople, with the history of David

as its subject. Now in the Metropolitan

Museum, the plates represent a series of depictions of episodes from the life

of David, including his anointing by Samuel. Samuel and Jesse are distinguished

from Jesse’s sons by their longer clothing, imparting greater dignity and from

each other by their gestures.

|

| Plate with David Anointed by Samuel Byzantine (Constantinople), c. 629-630 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

Similar scenes appeared in manuscript painting in both the

Greek and Latin speaking worlds during the Middle Ages.

Sometimes the images are narrative in character, trying to

depict the scene as it is described in the Bible

|

| Anointing of David by Samuel From a Psalter with Commentary Byzantine (Constantinople), c. 950 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Grec 139, fol. 3v |

|

| Jesse Presenting His Sons to Samuel and Samuel Anointing David From the Psalter-Hours of Guiluys de Boisleux French (Arras), c. 1246-1260 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M 730, fol. 19r |

At other times the image is almost schematic, presenting “just

the essentials”, that is, the figures of Samuel and David, with occasionally the figure of Jesse.

,%20Beginning%20of%2014th%20Century_Paris,%20Bibliotheque%20nationale%20de%20France_MS%20Francais%20155,%20fol.%2071v.jpg) |

| Samuel Anointing David From a Bible historiale by Guiard des Moulins French (Paris), Beginning of 14th Century Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 155, fol. 71r |

,%20c.%201310-1320_MS%20Royal%202%20B%20VII,%20fol.%20214v.jpg) |

| Queen Mary Master, Samuel Anointing David From The Queen Mary Psalter English (London), c. 1310-1320 London, British Library MS Royal 2 B VII, fol. 214v |

| ||||

| Jean Bodol (and Others), Samuel Anointing David From Grande Bible Historiale Completee French (Paris), c. 1371-1372 The Hague, Meermano Museum MS MMW 10 B 23, fol. 131r

|

Frequently the image is combined with images of other parts of David’s story, for instance, his defense of his sheep in killing a lion or his victory over Goliath.

|

| David Tending Sheep, Killing the Lion and Anointed by Samuel From a Psalter English, 1150-1160 London, British Library MS Cotton Nero C IV |

| ||||||

| Jesse Presenting David to Samuel and David With the Flock From Old Testament Miniatures French (Paris), c. 1250 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M 638, fol. 25v

|

Sometimes it is conflated with David’s later crowning as

king of Israel.

,%20c.%201175-1200_Paris,%20BNB_MS%20Latin%2010433,%20fol.%2038.jpg) |

| The Anointing of David As King From the Westminster Psalter English (London), c. 1175-1200 Paris,Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 10433, fol. 38r |

|

| Samuel Anoints David and David Is Crowned King From a Picture Bible French (St. Omer), c. 1190-1200 The Hague, Koninklijk Bibliotheek MS KB 76 F 5, fol. 43r |

,%20c.%201275-1300_Paris,%20Bibliotheque%20nationale%20de%20F_MS%20Latin%2010435,%20fol.%2027.jpg) |

| The Anointing of David From a Psalter French (Amiens), c. 1275-1300 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 10435, fol. 27r |

,%20Beginning%20of%2015th%20Century_Paris,%20Bibliotheque%20nationale%20de%20France_MS%20Francais%209,%20(2).jpg) |

| The Anointing of David From Bible historiale by Guiard des Moulins French (Paris), Beginning of 15th Century Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 9, fol. 288r |

|

| Bible Masters of the First Generation, Anointing of David From a History Bible Dutch (Utrecht), c. 1430 The Hague Koninklijk Bibliotheek MS KB 78 D 381, fol. 167v |

In summary, during the Middle Ages, there seems to have been no “template” image for this scene.

With the Renaissance, this changes. While there is still diversity of

presentation, of course, there is now remarkable conformity in

composition. David is now shown as an

adolescent or slightly younger boy, knelling before Samuel. He is almost always seen from the front, so

that his face is visible. Artists make

an effort to image the scene in its historic setting, although this appears to

be mostly based on their renewed knowledge of Roman art.

|

| Maarten van Heemskerck, Samuel Anointing David Drawing Dutch, c. 1555 Paris, Musée du Louvre, Cabinet des dessins |

|

| Maarten van Heemskerck, Samuel Anointing David Engraving made from the drawing above Dutch, c. 1556 Washington, National Gallery of Art |

|

| Federico Zuccaro, Samuel Anointing David Italian, c. 1560-1580 Paris, Musée du Louvre, Cabinet des dessins |

In addition to presenting the essential figures, Renaissance

and Baroque artists often (although not always) increased the number of figures in attendance to all of David's family and eventually to the

entire town of Bethlehem and its surroundings.

|

| Paolo Veronese, Samuel Anointing David Italian, c. 1555 Vienna, Kunsthistoriisches Museum |

|

| Friedrich Sustris, Samuel Anointing David German, c. 1570-1590 Edinburgh, National Galleries of Scotland |

|

| Aegidius Sadeler after a different design by Maarten de Vos, Samuel Anointing David Flemish, c. 1580-1596 Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum |

|

| Karel van Mander, Samuel Anointing David Dutch, c. 1591 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

|

| Copy After Frencesco Salviati, Samuel Anointing David Italian, 17th Century Paris, Musée du Louvre |

|

| Giovanni Lanfranco after Raphael, Samuel Anointing David Italian, 1607 Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum |

|

| Jan Victors, Samuel Anointing David Dutch, c. 1645 St. Petersburg, State Hermitage Museum |

|

| Jan Lievens, Samuel Anointing David Dutch, c. 1650-1670 St. Petersburg, State Hermitage Museum |

|

| Solomon de Bray, Samuel Anointing David Dutch, Second Half of the 17th Century Private Collection |

|

| Claude Lorrain, Landscape with Samuel Anointing David French, c. 1660-1680 Paris, Musée du Louvre |

|

| Mattia Preti, Samuel Anointing David Italian, c. 1670s Private Collection |

|

| Francisco Antolinez y Sarabia, Samuel Anointing David Spanish, 1685 Private Collection |

|

| Johann Georg Platzer, Samuel Anointing David Austrian, c. 1730-1760 Private Collection |

And this continued into the middle of the nineteenth century,

when the set subject for the 1842 competition for the extremely prestigious Prix de

Rome in history painting, given by the French Royal Academy of Arts, was "Samuel sacrant David".2 All painters who wished to be considered for the Prix de Rome were required to prepare paintings on this set subject.

The winner was a painter named Victor Biennoury, whose winning painting remained in the Ecole nationale superieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

|

| Francois-Leon Benouville, Samuel Anointing David French, 1842 Columbus (OH), Museum of Art |

The winner was a painter named Victor Biennoury, whose winning painting remained in the Ecole nationale superieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

|

| Victor Biennoury, Samuel Anointing David French, 1842 Paris, Ecole nationale superieure des Beaux-Arts |

As with so many of the Biblical scenes that he painted, the later nineteenth-century French painter, James Tissot, returned to a simpler telling of the story in which we are placed in the position of onlookers as Jesse presents his youngest, red-haired child, to Samuel, who stands beside us.

|

| James Tissot, Jesse Presents David to Samuel French, c. 1888-1894 New York, Jewish Museum |

© M. Duffy, 2018

- United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, Committee on Divine Worship. Liturgical Calendar for the Dioceses of the United States of America 2018. Available at: http://www.usccb.org/about/divine-worship/liturgical-calendar/upload/2018cal.pdf

- Foster, Carter E., with Bellenger, Sylvain and Cable, Patrick Shaw. French Master Drawings from the Collection of Muriel Butkin, Cleveland, The Cleveland Museum.

Excerpts from the Lectionary for Mass for Use in the

Dioceses of the United States of America, second typical edition © 2001, 1998,

1997, 1986, 1970 Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, Inc., Washington, DC.

Used with permission. All rights reserved. No portion of this text may be

reproduced by any means without permission in writing from the copyright owner.

,%201483_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Francais%2012,%20fol.%20165r.jpg)

,%20First%20Quarter%20of%2013th%20Century_London,%20British%20Library_MS%20Royal%201%20D%20X,%20fol.%2032.jpg)

,%20c.%201414-1422_London,%20British%20Library_MS%20Additional%2042131,%20fol.%2073.jpg)

,%20c.%201290-1295_P,%20BNF+MS%20Latin%201023,%20fol.%20%207v.jpg)

,%20c.%201398-1430_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Rothschild%202529,%2017v.jpg)

,%20c.%201447-1445_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Latin%204915,%20fol.%2046v.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment