,%20c.%201495-1505_New%20York,%20Pierpont_MS%20M%2052,%20fol.%20385v.jpg) |

| Master of the Older Prayerbook of Maximilian, Saint Gregory the Great From the Breviary of Eleanor of Portugal Flemish (Bruges), c. 1495-1505 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M 52, fol. 385v |

O God, who care for your people with gentleness and rule them in love, through the intercession of Pope Saint Gregory, endow, we pray, with a spirit of wisdom those to whom you have given authority to govern, that the flourishing of a holy flock may become the eternal joy of the shepherds. Through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son, who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit, God, for ever and ever. Memorial of Saint Gregory the Great, Mass for September 3rd.

Very few people in history have been given the distinction of the

title “the Great”. Most of them have

been soldiers or the rulers of great empires of the past. Among them are: Cyrus the Great, Ramses the Great, Alexander

the Great, Constantine the Great, Charlemagne (Charles the Great), Alfred the

Great, Catherine the Great. They are the

men and women who have ruled the Persian, the Egyptian, the Hellenistic, the

Roman, the Carolingian and the Russian Empires or, in the case of Alfred the

Great, the first of a line of English kings (and queens) over a thousand years

long. And then there are two

popes*: Saint Leo the Great and Saint

Gregory the Great, whose feast day is celebrated on September 3. I have written about Saint Leo the Great

previously. But today I would like to

introduce you to Saint Gregory.

Gregory the Great lived at the time in which the great day of one era

was slowly fading into sunset and another era was dawning. He was a man who was very much a product of a

world that was passing away, the world we now call the Late Antique, and he was

in part a creator of the world we call the Early Middle Ages. His influence reaches even to the present

day. And that influence is broad. The Europe we have known and its offshoots in

the Americas and elsewhere are part of his legacy.

Aristocrat

Gregory was born about 540 into a senatorial Roman family. That is a strange thing to say when you

realize that the Rome of his birth was a Rome that had ceased to be the center

of the world over one hundred years before his arrival. It had ceased to be Roman, if by using that

term we think of classical, Imperial Rome, and for almost that hundred years it

had been under the control of the Ostrogoths, one of the tribes of Germanic invaders

who had destroyed the Western Roman Empire. However, during Gregory’s childhood the

Eastern Roman Empire had recovered part of the Italian peninsula, including the

old capital city, so the old forms of life were still at least nominally in

place.

,%20c.%201055-1065_New%20York,%20Pierpont%20Morgan%20Library_MS%20M%20641,%20fol.%2022v.jpg) |

| Saint Gregory the Great From the Mont-Saint-Michel Sacramentary French (Norman), c. 1055-1065 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M 641, fol. 22v |

Gregory's family tree was interesting and had been Christian for a long time. One of his grandfathers had been Pope, another Pope was a great uncle, and his family tree was also interwoven with the church, having both male priests, female religious and lay office holders in the line. Gregory‘s father, Gordianus, was a senator and for a time he served as the Prefect of Rome, the highest senatorial office, dating back to the days of the Roman kings, before the Roman Republic or the Empire. He was also some kind of minor lay official in the Roman church. The family was relatively wealthy. They had estates in the area south of Rome as well as in Sicily and owned a ruined estate on one of the famous seven hills of Rome, the Caelian, which came to be deeply associated with Gregory himself.

Education and Early Career

As a boy and young man Gregory passed through the traditional

education for a man of his rank. He

learned the curriculum of the Trivium (grammar, logic and rhetoric) and the

Quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, music and astronomy) and, it would appear,

also had some specialized training in Roman law, probably indicating his family

plans that he should follow a political career.

His family household is also presumed to have been devout, based on its

connections to the Church and to Gregory’s later life. After the death of his father his mother

joined two of his aunts as vowed religious nuns.

At about the age of 30 he was elected as Prefect of Rome, the same rank his father had filled. This was the highest administrative office in the city of Rome, responsible for the running of the city. While nowhere near as powerful as it had been before the end of the Empire, it was still a great office, especially in its aura of antiquity and continuing authority during an unsettled period of the city’s history. The Prefect was responsible for keeping the city functioning for its citizens, in spite of the decline in population that followed the move of the Imperial administration to first Milan and then, after that city fell to the Ostrogoths (and later to the Lombards), to Constantinople.

Gregory the Monk

However, Gregory did not keep this office very long. After one term he renounced the office and

declared his intention to become a monk.

He used revenues from his family’s lands in Sicily to found several

monasteries, including one which he built among the ruins of his old family home

on the Caelian Hill in Rome. He himself

became a monk in that monastery, named Saint Andrew’s on the Caelian.

For several years he lived as a monk among the other monks on the

Caelian Hill. In 578, however, Pope

Pelagius II sent him as an envoy to Constantinople, to maintain good relations

with the eastern half of the Roman Empire, then developing into what is now

known as the Byzantine Empire. He does

not seem to have adapted to life in the East, however, and continued to live a

western monastic life while there.

After about six or seven years he was recalled to Rome and became

the abbot of his monastic foundation on the Caelian Hill. There he spent his time in scholarship and

contemplation and taught the monks and laity about the Scriptures. He also wrote a great deal, including the

books for which he became most famous, such as the commentary on the Book of

Job, which became known as the Moralia in Job. He also became the secretary and chief

advisor to Pope Pelagius II.

|

| Follower of Fra Angelico, The Papacy Is Offered to Saint Gregory the Great Italian, c. 1435 Philadelphia, Museum of Art |

Gregory Becomes Pope

When Pelagius II died during a plague in 589, Gregory was elected as

his successor. Gregory was not

altogether happy in the choice and tried to avoid becoming Pope. However, in the end he assented. A legend appeared, about a hundred years

after his death, that he ran away from Rome and hid in a cave in the

forest. There he was discovered when a

flash of light revealed him to those looking for him and they were able to

seize him and return him to the city.

,%20c.%201323-1326_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Latin%2010483,%20fol.%20160v.jpg) |

| Workshop of Jean Pucelle, Saint Gregory Discovered in His Hiding Place From the Breviary de Belleville French (Paris), c. 1323-1326 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 10483, fol. 160v |

Gregory may have been a reluctant Pope, but once in office he was certainly an energetic one. He continued to write and to preach. He dispatched missionaries to parts of the world not yet touched by the Christian Gospel and attempted to unify the parts that were Christianized. He instituted reforms aimed at standardizing the liturgy in the disjointed world of his time and may have been responsible for the earliest forms of what we know today as Gregorian chant. He took over the day to day running of the city of Rome, as lay authority on the Italian peninsula was lost by Byzantium and fragmented among the various barbarian invaders. The form of papal government that we know today had its beginnings during his reign.

,%20c.%201300=1325_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Francais%20183,%20fol.%20237v.jpg) |

| Master of the Roman de Fauvel, Saint Gregory Preaching From the Vies de saints French (Paris), c. 1300-1325 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 183, fol. 237v |

Some idea of the extent of Gregory’s actions can be gained from

this passage in a brief essay on his pontificate written by the British historian

Eamon Duffy (no relation that I’m aware of) in his book Ten Popes Who Shook the

World. “Almost nine hundred of Gregory’s

letters survive, so we know more about his pontificate than that of any other

pope of late antiquity. The range of his activities, the grip and minuteness of

his tireless involvement in the myriad responsibilities of the greatest

bishopric in the Christian world are astonishing even in our time of global

expansion. His concerns stretched from Visigothic Spain and eastern Gaul to

Africa, Greece and the Balkans. His letters show him organising corn supplies

from Sicily to feed the famine-stricken people of central Italy; enforcing

clerical celibacy; overseeing the administration of the papal horse ranches;

rebuking bishops who were mistreating Jews or who could not get on with their

senior clergy; buying the liberty of Roman citizens enslaved by the Lombards;

overhauling the administration of papal lands to eliminate corruption; securing

trusted Roman clerics, especially monks, for vacancies in provincial

bishoprics; defying imperial legislation designed to prevent men of military

age from becoming monks; sending gifts of relics or sacred books to encourage

pious princes; cultivating the Catholic wives of pagan or heretical rulers,

even among the Lombards, whose souls, as a bishop, he wanted to save (though,

as a proud and aggrieved Roman, he loathed them).” Also, in Duffy’s words “Struggling to hold

back the collapse of the classical world, this aristocratic Roman monk had

unwittingly invented Europe.”1.

Iconography of Saint Gregory the Great

Image as Pope

Some of the iconography associated with Saint Gregory the Great is

simply that which shows him as the Pope.

There is little reference in any of these images to the material that

would form the bulk of his iconography.

Usually shown in either a seated or a standing posture, giving a blessing,

he may carry a book or the distinctive cross that is the symbol of the universal

papal authority (distinct from the more common crozier or shepherd hook of a local

bishop or archbishop). One interesting

sidelight of this (and all the other images of Saint Gregory) is that one can

trace the development of the distinctive papal headgear, the triple tiara, from nothing special to a variation of the episcopal miter to a conical headdress to the eventual beehive

shape that it had in the modern era.

,%20c.%201050_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Latin%20818,%20fol.%202v.jpeg) |

| Saint Gregory the Great From a Missal French (Champagne), c. 1050 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 818, fol. 2v |

|

| Bernardo Daddi, Saint Gregory the Great Italian, c. 1334 Cambridge, Harvard Art Museums, Fogg Museum, Gift of Miss Margaret Whitney |

|

| Saint Gregory the Great German, c. 1400 Soest, Protestant Parish Church of Saint Mary zur Wiese and Wiesenkirche |

,%20c.%201415-1425_New%20York,%20Pierpont%20Morgan%20Library_MS%20M%20374,%20fol.%20122v.jpg) |

| Gold Scrolls Group, Saint Gregory the Great From a Missal Flemish (Bruges), c. 1415-1425 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M 374, fol. 122v |

|

| Master of the Morgan Infancy Cycle, Saint Gregory the Great From a Book of Hours Dutch (Delft), c. 1415-1420 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M 866, fol. 146v |

,%20c.%201435-1445_New%20York,%20Pierpont%20Morgan%20Library_MS%20M%20917,%20fol.%20240v.jpg) |

| Master of Catherine of Cleves, Saint Gregory the Great From the Hours of Catherine of Cleves Dutch (Utrecht), c. 1435-1445 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M 917, fol. 240v |

|

| Bicci di Lorenzo, Saint Gregory the Great Italian, c. 1447 Arezzo, Church of San Francesco |

,%20c.%201450=1475_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Francais%20299,%20fol.%201r.jpeg) |

| Gregory the Great and His Secretary From the Fleur des histoires by Jean Mansel Flemish (Bruges), c. 1450-1475 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 299, fol. 1r |

,%20c.%201450-1460_The%20Hague,%20KB_MS%20KB%2076%20F%202,%20fol_%20209r.jpg) |

| Jean le Tavernier and Follower, Saint Gregory the Great From the Hours of Philip of Burgundy Flemish (Oudenaarde), c. 1450-1460 The Hague, Koninklijk Bibliotheek MS KB 76 F 2, fol. 209r |

,%20c.%201470-1480_New%20York,%20Pierpont_MS%20G%201%20II,%20fol.%20264r.jpg) |

Followers of the Coëtivy Master, Saint Gregory the Great From a Book of Hours French (Loire), c. 1470-1480 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS G 1 II, fol. 264r |

|

| Nicolas Cordier, Saint Gregory the Great French, c. 1602 Rome, Church of San Gregorio Magno al Celio |

|

| Francisco de Zurbaran, Saint Gregory the Great Spanish, c. 1626-1627 Seville, Museo de Bellas Artes |

|

| Saint Gregory the Great German, c. 1787 Huysburg am Harz, Monastery Church of the Assumption |

|

| Francisco Goya y Lucientes, Saint Gregory the Great Spanish, c. 1797 Madrid, Museo Romantico |

|

| Carl Heinrich Hermann and Assistants, Saint Gregory the Great German, 1836 Munich, Church of Saint Ludwig |

|

| Lorenz Benz, Saint Gregory the Great German, c. 1865 Schwäbisch Gmünd, Sankt Josefskapelle |

Miracles

The Plague Procession

One of the first things that confronted the new Pope was a plague then raging across the known world. This is probably one of the aftershocks of the great plague of Justinian, which had devastated both the Roman Empire (East and West) and Persian Empire around the middle of the sixth century. This plague is now thought to have been an instance of the bubonic plague, an earlier version the Black Death, that ravaged Europe much later (during the fourteenth century). As the Pope was by now the only real ruler of the city of Rome, Gregory did what he could. In an era when nothing was known about what caused the plague and how it spread people were left with few options. Chief among them was penance and prayer, since it was believed that all such illnesses were a punishment from God for the sinful lives of people. And this is what Gregory did. He ordered a large procession of the people of Rome, originating in the seven pilgrimage churches of the old city, meeting eventually at the tomb of Saint Peter on the Vatican side of the river Tibur. As the procession converged at the crossing point of the river, near the tomb of Emperor Hadrian, Gregory had a vision of the angel Michael, holding a drawn sword above his head, standing on the top of the structure. As Gregory watched, Michael sheathed his flaming sword and disappeared. This was interpreted as indicating that the penitential procession had ended God’s anger against the city and that the plague would shortly end. It did.

As a response, Pope Gregory ordered the construction of a chapel to Saint Michael the Archangel within the tomb structure. From that day to this, Hadrian’s Tomb became known as Castel Sant’Angelo.

|

| Coppo di Marcovaldo, Saint Gregory Ordering the Building of a Chapel to the Archangel Michael at Hadrian's Tomb Italian, c. 1250-1255 San Casciano in Val di Pesa, Museo d'Arte Sacra |

|

| Lorenzo Ghiberti, Saint Gregory Ordering the Building of a Chapel to the Archangel Michael at Hadrian's Tomb Italian, c. 1421-1424 Florence, Baptistry |

Images of this procession abound in the artistic record but are most frequent after the middle of the fourteenth century. This is for good reason, as the years 1347-1348 were the height of the next major outbreak of bubonic plague throughout the same territories that had been decimated in the sixth century.

,%20c.%201385-1390_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Latin%20757,%20fol.%20155r.jpeg) |

| Giovanni di Benedetto & Workshop, Saint Gregory's Procession From a Book of Hours Italian (Milan), c. 1385-1390 Paris, Bibliotheeque nationale de France MS Latin 757, fol. 155r |

|

| Giovanni di Paolo, Procession of Saint Gregory Italian, c. 1450-1475 Paris, Musée du Louvre |

|

| Anonymous, The Miracle of Castel Sant'Angelo Spanish, c. 1500 Philadelphia, Museum of At |

|

| Jacopo Zucchi, The Procession of Saint Gregory Italian, c. 1578-1580 Vatican City, Pinacoteca Vaticana |

|

Horace Le Blanc, Procession of Saint Gregory to Castel Sant'Angelo in 590 French, 1625 Dijon, Musée d'Art Sacré |

|

Jacques Callot, Saint Gregory in Procession near Hadrian's Tomb From Les images de tous les saints et santes del'année French, c. 1632-1635 London, Trustees of the British Museum |

The image appears to have remained popular so long as Europe remained vulnerable to devastating bouts of bubonic plague.

Other Miracles

Several other miracles are credited to Saint Gregory during his

lifetime and afterwards. However, these

make up only a very small sliver of his iconography, especially in comparison with other saints.

|

| Legends of Saint Gregory From a Book of Legends French, c. 1250-1300 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Nouvelle acquisition francaise 23686, fol. 132r |

,1348_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Francais%20241,%20fol.%2074r.jpg) |

| Richard de Montbaston, Saint Gregory and the Mendicant Angel From the Legenda aurea by Jacobus de Voragine French (Paris),1348 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 241, fol. 74r |

|

| Domenico Ghirlandaio, Announcing the Death of Saint Fina Italian, c. 1473-1475 San Gimignano, Collegiata |

Inspired Writer

One of the most frequent images of Saint Gregory are those that depict

him as an inspired writer. Beginning

with images made not long after his death and continuing for a thousand years,

he has been depicted as a writer, usually (though not always) seated and writing,

receiving inspiration, if not outright dictation, from a dove, the visual

representation for the Holy Spirit. This

is the same pose as was generally used for “portraits” of the four evangelists

that usually appeared in copies of the Bible.

That Saint Gregory should be depicted this way speaks volumes about the

respect in which his writings was held.

|

| Saint Gregory the Great From the Sacramentary of Charles the Bald French, c. 850 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 1141, fol. 3r |

|

| Master of the Vienna Gregory Plaque, Saint Gregory Writing Mosan, End of the 10th Century Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Kunstkammer |

|

| Author Portrait of Saint Gregory the Great From the Dialogues by Gregory the Great German, First Half of the 12th Century London, British Library MS Harley 3011, fol. 59v |

,%20c.%201143-1178_Cleveland,%20Museum%20of%20Art.jpg) |

| Abboy Frowin, Gregory and His Deacon, Peter Title Page from the Moralia in Job by Saint Gregory Swiss (Engelberg), c. 1143-1178 Cleveland, Museum of Art |

,%20c.%201150-1175_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Latin%202288,%20fol.%201v.jpeg) |

| Author Portrait of Saint Gregory From the Registrum epistolarum of Gregory the Great Flemish (Tournai), c. 1150-1175 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 2288, fol. 1v |

,%20c.%201188-1200_Chicago,%20Art%20Institute.jpg) |

| Saint Gregory the Great Page from a Life of Saint Gregory German (Weingarten), c. 1188-1200 Chicago, Art Institute |

,%20c.%201190=1200_The%20Hague,%20KB_%20MS%20KB%2076%20F%20f5,%20fol.%2025v.jpg) |

| Saint Gregory Writing From a Picture Bible French (St. Omer), c. 1190-1200 The Hague, Koninklijk Bibliotheek MS KB 76 F f5, fol. 25v |

,%20c.%201385-1390_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Latin%2018014,%20fol.%2075r.jpg) |

| Jacquemart, Saint Gregory Receiving Inspiration From the Petites heures de Jean de Berry French (Bourges), c. 1385-1390 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 18014, fol. 75r |

,%201409_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Latin%20919,%20fol.%20100r.jpg) |

| Maitre de la Mazarine and Workshop, Saint Gregory and a Scribe From the Grandes heures de Jean de Berry French (Paris), 1409 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 919, fol. 100r |

|

Michael Pacher, Saint Gregory the Great From the Altar of the Church Fathers German, 1480 Munich, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Alte Pinakothek |

,%201485_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Latin%202231%20(2),%20fol.%2025r.jpeg) |

| Gaspare Romano, Saint Gregory the Great From the Moralia in Job by Saint Gregory the Great Italian (Roman), 1485 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 2231 (2), fol. 25r |

|

| Peter Paul Rubens, Ecstasy of Saint Gregory the Great Flemish, 1608 Grenoble, Musée des Beaux-Arts |

|

| Domenico Feti, Saint Gregory the Great Italian, c. 1610-1520 Lille, Palais des Beaux-Arts |

|

| Jusepe de Ribera, Saint Gregory the Great Spanish, c. 1614 Rome, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica |

|

| Anonymous, Saint Gregory the Great Spanish, c. 1630 Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado |

|

| Jacopo Vignali, Saint Gregory the Great Italian, c. 1630 Baltimore, The Walters Art Museum |

|

| Fray Juan Andres Rizi, Saint Gregory the Great Spanish, c. 1645-1655 Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado |

|

Lucas Franchoys the Younger. Saint Gregory the Great Flemish. c. 1650 Pau, Musée des Beaux-Arts |

|

| Domenico Maggiotto, Saint Gregory the Great Italian, c. 1760s Saint Petersburg, State Hermitage Museum |

Theologian and Philosopher

On a different, more human, level, Gregory was also depicted in the act of writing or alluding to his written work.

,%20c.%201150-1175_paris,%20BNF_MS%20Latin%202287,%20fol.%201v.jpeg) |

| Saint Gregory the Great From the Registrum epistolarum by Saint Gregory the Great French (Saint-Amand), c. 1150-1175 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 2287, fol. 1v |

|

| Saint Gregory the Great Italian, c. 1320 London, Victoria and Albert Museum |

,%20c.%201445-1455_NY,%20Pierpont_MS%20M%20184,%20fol.%201r.jpg) |

| Pope Gregory Presenting the Life of Saint Benedict to the Monks From the Vita S. Benedicti by Saint Gregory the Great Italian (Padua), c. 1445-1455 NY, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M 184, fol. 1r |

,%20c.%201455-1465_New%20York,%20Pierppont_MS%20M%20387,%20fol.%20100v.jpg) |

| Guillaume Vrelant and Workshop, Saint Gregory the Great From a Book of Hours Flemish (Bruges), c. 1455-1465 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M 387, fol. 100v |

|

| Follower of Loyset Li, Saint Gregory Teaching From the Homilies on the Four Evangelists by Saint Gregory the Great Flemish, c. 1480-1490 The Hague, Koninklijk Bibliotheek MS KB 129 C 4, fol. 1r |

|

| Raphael, Justice Italian, 1511 Vatican City, Apostolic Palace, Stanza della Segnatura |

|

| Anton Wierix II After Maerten de Vos, Saint Gregory the Great in His Study From the Four Fathers of the Church Flemish, 1585 Cambridge, Harvard Art Museums, Fogg Museum, Gift of Barbara Ketcham Wheaton |

|

| Arnould de Vuez, Saint Gregory the Great French, c. 1700 Lille, Palais des Beaux-Arts |

Doctor of the Church

However, a much larger group of images depict Gregory along with

several other respected Christian writers as one of the Fathers of the Latin Church. The four men generally included in the group are

Saints Jerome, Ambrose, Augustine and Gregory.

Images usually show all four, but in some Gregory is paired with only

one other and that one is usually Saint Jerome.

|

| Jacobello Alberegno, Crucified Christ Between the Virgin and Saint John the Evangelist, with Saints Gregory and Jerome Italian, c. 1375-1397 Venice, Galleria dell'Accademia |

,%20c.%201410_The%20Hague,%20KB_MS%20KB%2072%20A%2022,%20fol.%206r.jpg) |

| The Orosius Master, God wotjSaints Augustine, Gregory, Ambrose and Jerome From City of God by Saint Augustine of Hippo French (Paris), c. 1410 The Hague, Koninklijk Bibliotheek MS KB 72 A 22, fol. 6r |

|

| Attributed to Joan Rosato, Mystical Crucifixion, with the Four Doctors of the Church and Saint Paul Contemplating the Crucifixion Spanish, c. 1445 Princeton, Princeton University Art Museum |

|

| Fathers of the Church Saints Gregory and Ambrose French or Flemish, c. 1480 Paris, Musée du Louvre |

|

| Madonna and Child with the Four Church Fathers German, c. 1490 Hersbruck, Protestant Parish Church |

|

| Pedro Berruguete, Saints Gregory the Great and Jerome Spanish, c. 1495-1500 Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado |

|

Abraham Van Diepenbeeck, The Four Doctors of Church Flemish, c. 1650-1660 Bordeaux, Musée des Beaux-Arts |

Reform of the Liturgy

I did not find many images that referred to this specific part of

Saint Gregory’s legacy, although some other images that I have classified

elsewhere may be related to this subject.

,%20End%20of%20the%2011th%20Century_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Latin%202799,%20fol.%202r.jpg) |

| Saint Gregory the Great From the Regula pastoralis by Saint Gregory the Great French (Limoges), End of the 11th Century Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 2799, fol. 2r |

|

| Taddeo Crivelli, Saint Gregory the Great From the Gualenghi-d'Este Hours Italian, c. 1469 Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum MS Ludwig IX 13, fol. 172v |

A Famous Decision

One of the most distinctive subjects in the life and iconography

of Saint Gregory was his decision to send a missionary group of monks to the

kingdom of Kent in England in the 590s.

The well-known story is that Gregory happened to see some unusual

looking slaves for sale in the Roman slave market as he passed by on the

street. They were young men with very

pale skin and blonde hair, an unusual combination in the Mediterranean world of

the time. He asked where they came from

and was told that they were from Britain.

Now, by this time, formerly Romanized, Christian Britain had been

swallowed up by a wave of immigration from the pagan north of Germany. Tribes like the Angles, Saxons and Jutes had

taken over territory in the eastern half of the island and caused a great

emigration of the former residents who were Christian. Those people had fled their homes to move

west, into what later became Wales, or across the sea to the continental area of

Brittany, to which they carried their identity as Britons. Therefore, the people Gregory was asking

about were either Germanic captives seized in raids or young men simply traded away for

luxury goods from within the recently Germanized areas. They were identified to him as being Angles

from Britain. Struck by their shining

appearance Gregory is supposed to have remarked “Non angli, sed angeli!” (not

Angles, but angels). He determined that

this angelic looking people should be converted and sent a party of monks from the abbey on the Caelian

Hill, under the leadership of a monk named Augustine, whom he anointed as bishop,

to the king of Kent in southern Aengleland.

The mission was successful and that is why the Archbishop of Canterbury

is today the leading primate in the Church of England.

|

| Francois Nouviaire, Saint Gregory the Great Commissioning Saint Augustine of Canterbury French, c. 1834 Stenay, Church of Saint Gregory |

|

| J. Fournier, Saint Gregory the Great Sends Saint Melec to Evangelize the Anglo-Saxons French, 1899 Guegon, Church of Saint Melec |

Legendary Events

The iconography of Saint Gregory outlined above reflects those aspects of Saint Gregory’s life that are based on fact, on things that really happened. Sometimes a legendary event may have been added to a real one, as for instance the appearance of the angel atop Hadrian’s Tomb during the plague procession requested by the newly installed pope in 590. But at least the events depicted were at the basic level real. Similarly with images of Gregory as a writer and Father. They are based on the respect in which his writings were held by subsequent generations. However, there are some other elements of the iconography that seem to be wholly fantastical. While there may have been some real event at the base of one or more is extremely difficult to say with any degree of certainty.

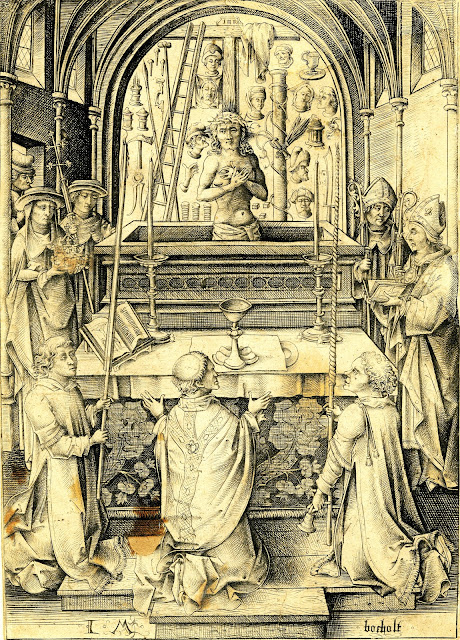

Mass of Saint Gregory

The most obvious example of this is also the most popular. This is the so-called Mass of Saint Gregory

which was extremely popular in the fifteenth century and somewhat sporadically

thereafter.

|

Anonymous, The Mass of Saint Gregory German, 15th Century Paray-le-Monial, Musée du Hieron |

The subject of this iconography depicts Pope Gregory at the moment of or just after the Consecration of the Mass, often, but not always, attended by deacons and other members of the papal court. As the pope kneels or elevates the Host a vision of Christ as the crucified Man of Sorrows appears in place of the altarpiece. This goes back to a story told by one of his early biographers. Supposedly, there was a member of the papal household who doubted the real presence of Jesus in the piece of bread on the altar. In other words, this person doubted the central Catholic doctrine of Transubstantiation, that what had been simple bread becomes the body, blood, soul and divinity of Jesus Christ through the words of Consecration, while still looking outwardly like bread. The vision of the Man of Sorrows, beaten, bloodied, dead but still living, was given to reinforce the doctrine and to reinforce the wavering faith of the doubter.

,%20c.%201430-1440_New%20%20York,%20Pierpont%20Morgan%20Library_MS%20M%20241,%20fol.%2040v.jpg) |

| Master of the Munich Golden Legend, the Mass of Saint Gregory From the Hours of Duke Arthur of Brittany French (Angers), c. 1430-1440 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M 241, fol. 40v |

,%20c.%201455-1465_New%20York,%20Pierpont_MS%20M%20194,%20fol.%20145r.jpg) |

| The Rambures Master, The Mass of Saint Gregory From a Book of Hours French (Amiens), c. 1455-1465 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M 194, fol. 145r |

,%20c.%201475-1500_The%20Hague,%20KB_MS%20KB%2076%20G%2013,%20fol.%2098v.jpg) |

| Masters of Hugo Janszoon van Woerden, The Mass of Saint Gregory From a Book of Hours Dutch (Leyden), c. 1475-1500 The Hague, Koninklijk Bibliotheek MS KB 76 G 13, fol. 98v |

Often the apparition is a simple one of Jesus as the Man of Sorrows, alone. But frequently the simple image is compounded, and we see not only Jesus, but the entire panoply of the Instruments of the Passion. There may be angels and, most interestingly, there may be representations of those who tortured or condemned Jesus as well. The space around the altar can become quite crowded.

,%20c.%201455-1460_The%20Hague,%20KB_MS%20KB%20135%20E%2040,%20fol.%20110v.jpg) |

| The Mass of Saint Gregory From a Book of Hours Dutch (Utrecht), c. 1455-1460 The Hague, Koninklijk Bibliotheek MS KB 135 E 40, fol. 110v |

,%20c.%201465-1470_New%20York,%20Pierpont_MS%20M%20248,%20fol.%20118r.jpg) |

| Jean Colombe and Workshop, The Mass of Saint Gregory From a Book of Hours French (Bourges), c. 1465-1470 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M 248, fol. 118r |

|

| Attributed to Diego de la Cruz, The Mass of Saint Gregory Spanish, c. 1490 Philadelphia, Museum of Art |

,%20c.%201490-1500_The%20Hague,%20KB_MS%20KB%2076%20F%2016,%20fol.%20120r.jpg) |

| Master of Antoine of Burgundy, The Mass of Saint Gregory From a Book of Hours Flemish (Mons), c. 1490-1500 The Hague, Koninklijk Bibliotheek MS KB 76 F 16, fol. 120r |

,%20c.%201490_The%20Hague,%20KB_MS%20KB%2076%20G%2016,%20fol.%20149v.jpg) |

| Masters of the Dark Eyes, The Mass of Saint Gregory From a Book of Hours Dutch (Utrecht), c. 1490 The Hague, Koninklijk Bibliotheek MS KB 76 G 16, fol. 149v |

,%20c.%201495-1505_New%20%20York,%20Pierpont_MS%20H%208,%20fol.%20168r.jpg) |

| Jean Poyer, The Mass of Saint Gregory From the Hours of Henry VIII French (Tours), c. 1495-1505 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS H 8, fol. 168r |

|

| Follower of Simon Bening, The Mass of Saint Gregory From a Book of Hours Flemish, c. 1500-1525 The Hague, Meermano Museum MS RMMW 10 E 3, fol. 190v |

In addition, on the Pope's side of the altar, facing this apparition, there may be no one else, or there may be only members of the papal chapel, or the room may be full of spectators, including donors.

|

| Anonymous, The Mass of Saint Gregory French, c. 1438 Paris, Musée du Louvre |

|

| The Mass of Saint Gregory From a Book of Hours Flemish, c. 1465-1475 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M 93, fol. 7v |

|

| Simon Marmion, The Mass of Saint Gregory From a Book of Hours Flemish, c. 1475-1485 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M 6, fol. 154r |

|

| Israhel van Meckenem, The Mass of Saint Gregory German, c. 1480-1485 London, Trustees of the British Museum |

|

| Master of the Heiligen Sippe, The Mass of Saint Gregory German, 1486 Utrecht, Museum Catharijneconvent |

|

| Anonymous, The Mass of Saint Gregory Flemish, c. 1500 Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum |

|

| Triptych of the Mass of Saint Gregory Flemish, 15th Century Paris, Musée du Cluny, Musée national du Moyen Age |

|

Albrecht Dürer, The Mass of Saint Gregory German, 1511 London, Trustees of the British Museum |

|

| Adriaen Ysenbrandt, The Mass of Saint Gregory Flemish, c. 1510-1550 Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum |

|

| Adriaen Ysenbrandt, The Mass of Saint Gregory Dutch, c. 1515-1530 Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado |

,%20c.%201515_1520_New%20York,%20Pierpont_MS%20M%201166,%20fol.%2050v.jpg) |

| Master of Claude de France, The Mass of Saint Gregory From the Prayer Book of Claude de France French (Tours), c. 1515-1520 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M 1166, fol. 50v |

|

| Workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder, Teh Mass of Saint Gregory with Cardinal Albrecht von Brandenburg German, c. 1520-1525 Munich, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Alte Pinakothek |

Cardinal Albrecht von Brandenburg may have had hopes of becoming Pope, since he commissioned two versions of this subject from Lucas Cranach and had himself added as a character in each.

|

| Workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder, The Mass of Saint Gregory with Cardinal Albrecht von Brandenburg German, c. 1520-1525 Munich, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Alte Pinakothek |

,%201533_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Nouvelle%20acquisition%20latine%20302,%20fol.%2076v.jpeg) |

| The Mass of Saint Gregory From the Hours of Antoine le Bon French (Lorraine), 1533 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Nouvelle acquisition latine 302, fol. 76v Here the vision is not just that of the Man of Sorrows. It is actually the image of the Sorrow of God, in which God the Father holds the Man of Sorrows on his lap, presenting the Son to us as a sign of his love and forgiveness, while the dove of the Holy Spirit hovers nearby. |

Christ may stand or sit or be upheld by angels. He may also direct the blood from his pierced side into the chalice on the altar, further reinforcing the reality of His Presence in the consecrated wine, which has become his Blood.

,%20c.%201455-1465_New%20York,%20Pierpont_MS%20M%201067,%20fol.%209r.jpg) |

| Master of Adelaide of Savoy, The Mass of Saint Gregory From Fragment of a Book of Hours French (Loire Valley), c. 1455-1465 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M 1067, fol. 9r |

,%20c.%201492=1493_paris,%20BNF_MS%20Latin%2010491,%20fol.%20214v.jpg) |

| Georges Trubert, The Mass of Saint Gregory From Diurnal of Rene II of Lorraine French (Nancy), c. 1492-1493 Paris, Bibliotheue nationale de France MS Latin 10491, fol. 214v |

_1495_1505_Morgan_h1.115r.jpg) |

| Possibly Robert Boyvin, The Mass of Saint Gregory From a Book of Hours French (Rouen), c. 1495-1505 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS H 1, fol. 115r |

,%201531_New%20York,%20Pierpont_MS%20M%20451,%20fol.%20113v.jpg) |

| Simon Bening, The Mass of Saint Gregory From a Book of Hours Flemish (Bruges), 1531 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M 451, fol. 113v |

The iconography of this very important image is quite diverse in spite of the uniformity of its message of belief in the presence of Christ in the consecrated Host.

|

| Altarpiece of the Eucharist from the monastery of Averbode Flemish, c. 1500-1525 Paris, Musée du Cluny, Musée national du Moyen Age |

What may be one of the most astonishing images, however, is one that was made in the Spanish colonies of the New World in 1539, just 47 years from the date of the Columbus landing and only 18 years after the conquest of the Aztec Empire by Hernan Cortez. It was commissioned by “Diego de Alvarado Huanitzin (nephew and son-in-law to Moctezuma II, the last Aztec ruler of Mexico” as a gift for Pope Paul III in gratitude for his defense of native Americans in 1537, which ended their enslavement. It is composed of iridescent bird feathers and gold anchored on a wooden plaque. Featherwork was a long-standing artistic medium in pre-colonial Mexico, but its use for a European subject was new. The design of the image is based on a print by Israhel van Mechenen. The work demonstrates several things: the acceptance by native Americans of the new religious and political order, growing belief in the doctrines of Christianity, the far-reaching influence of printed images. It is an extremely precious object.

|

| The Mass of Saint Gregory Mosaic Made of Wood and Bird Feathers Mexican (Nahua), 1539 Auch, Musée des Jacobins |

Discussions on the Eucharist

There is a significant later offshoot from the subject matter of the

Mass of Saint Gregory. That iconography

aimed to convince the viewer of the reality of the doctrine of

Transubstantiation. This specific subject

was almost entirely a northern European subject and almost entirely confined to

the fifteenth century. However, other artists,

from a later period came to deal with the same subject matter in a somewhat

different way. They presented a group of

saints, very often the Church Fathers, discussing the Eucharist and offering praise. But the bloody figure of the Man of Sorrows does

not appear in these images. Raphael led

the way with the famous painting of the Disputà in the Stanza della Segnatura at the Vatican. There, however, instead of the Man of Sorrows

appearing above the altar, it is the glorified Risen Christ in Majesty that appears,

while a throng of theologians and other saints salute him, both in His heavenly glory and his Eucharistic Presence. Prominent among them is Pope Saint Gregory

the Great.

|

| Rafael, Disputation of the Holy Sacrament, known as the Disputà Italian, c. 1510-1511 Vatican City, Apostolic Palace, Stanza della Segnatura |

Other, later artists skipped the figure of Christ entirely, presenting the Eucharist only through the image of a Host in the monstrance, as used for Benediction and Adoration services.

|

| Peter Paul Rubens, The Defenders of the Eucharist (Saints Ambrose, Augustine, Gregory the Great, Clare, Thomas Aquinas, Norbert and Jerome) Flemish, 1625 Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado |

|

| Abraham Bloemart, The Four Doctors of the Church Discussing the Eucharist Flemish, 1632 Private Collection |

Visions of Saint Gregory

A later development in the iconography of Saint Gregory was to

depict him in the role of visionary.

While he was a man of prayer and deep contemplation, he was not depicted

as a visionary until nearly a thousand years after his death.

The image below refers back to the subject of the Mass of Saint Gregory, but here the vision is given to Gregory alone, privately, and depicts Christ actually hanging on the Cross.

,%20c.%201535-1545_New%20York,%20Pierpont_Ms%20M%20696,%20fol.%20258v.jpg) |

| Master of Charles V, A Vision of Saint Gregory the Great From the Hours of Charles V Flemish (Brussels), c. 1535-1545 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M 696, fol. 258v |

However, most of the vision paintings depict Gregory receiving a vision of the Madonna and Child in glory in heaven.

.jpg) |

| Melchiorre Gherardini, The Vision of Saint Gregory Italian, c. 1650 Saint Petersburg, State Hermitage Museum |

|

| Sebastiano Ricci, The Vision of Saint Gregory Italian, c. 1700-1730 Padua, Basilica di Santa Giustina |

|

| Francesco Fontebasso, Saints Gregory the Great and Vitalis Interceding with the Virgin and Child for the Souls in Purgatory Italian, c. 1730-1731 Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum |

Gregory as Member of a Group of Saints

Finally, Gregory’s iconography extends to including him among a

group of saints, in a Sacra Conversazione. Originating as part of large altarpieces, these images were useful in providing a means for a church or a patron

to include many different, often entirely unrelated saints in a single group to

satisfy personal or parochial needs to include a range of patron saints.

|

| Saints Gregory, Benedict and Cuthbert From the Benedictional of Aethelwold English, c. 963-984_London, British Library MS Additional 49598, fol. 1r |

|

| Giovanni da Milano, Saints James the Greater and Gregory the Great Italian, 1363 Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi |

|

| Masolino di Panicale, Saints Gregory and Matthias From the Santa Maria Maggiore Altarpiece Italian, c. 1428-1429 London, National Gallery |

|

| Andrea Mantegna, The Trivulzio Madonna Italian, c. 1494-1497 Milan, Civico Museo d'Arte Antic, Castello Sforzesco |

|

| Pinturicchio, The Virgin Mary in Heaven with Saints Gregory the Great and Benedict Italian, 1512 San Gimignano, Museo Civico |

|

| Attributed to Lorenzo di Credi, Madonna and Child with Saints Joseph, John the Baptist, Gregory the Great, a Deacon Saint and a Female Saint Italian, c. 1525-1527 Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi |

|

| Juan de Borgoňa the Younger, Saints Gregory the Great, Sebastian and Thyrsus Spanish, 16th Century Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado |

|

| Stained Glass Panel with the Arms of Gebhard II Dornsperger, Abbot of Petershausen Ben Abbey German, 1540 Paris, Musée du Louvre |

|

| Gregorio Pagani, Madonna and Child with Saints Margaret of Cortona, Gregory, Francis and John the Baptist Italian, 1592 Saint Petersburg, State Hermitage Museum |

|

| Peter Paul Rubens, Saint Gregory the Great with Saints Maurus, Papianus and Domitilla Flemich, 1608 Berlin, Gemäldegalerie der Staatliche Museen zu Berlin |

|

| Peter Paul Rubens, Saints Maurus, Gregory, Papianus, Domitilla, Nereus and Achilleus Flemish, 1608 Salzburg, Salzburger Barock museum |

Gregory As One of The Confessors

One special group of saints among these “conversations” are the confessors. This is a group formed by saints who by their lives or by their writings proclaimed belief in Christ and the Church without being subjected to martyrdom for those beliefs. In this group you will find some familiar figures: Augustine, Jerome, Francis of Assisi, Dominic, Thomas Aquinas, Louis IX and Gregory the Great.

,%20c.%201385-1390_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Latin%2018014,%20fol.%20105v%20(2).jpg) |

| Jacquemart, The Confessor Saints From the Petites heures de Jean de Berry French (Bourges), c. 1385-1390 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 18014, fol. 105v |

|

| Lorenzo Monaco, A Group of Confessor Saints From the San Benedetto Altarpiece Italian, c. 1407-1409 London, National Gallery |

,%20c.%201503-1508_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Latin%209474,%20fol.%20181v.jpeg) |

| Jean Bourdichon, Confessor Saints From the Grandes heures d'Anne de Bretagne French (Tours), c. 1503-1508 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 9474, fol. 181v |

,%201503_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Francais%20594,%20fol.%20376r.jpeg) |

| Master of the Triumphs of Petrarch, Allegory-The Triumph of the Trinity From Triumphs by Petrarch French (Rouen), 1503 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 594, fol. 376r |

Not a bad group to be numbered with!

© M. Duffy, 2022

- Duffy, Eamon. Ten Popes Who Shook the World, New Haven and London, Yale University Press, 2011, pages 50-58. This is a good brief discussion of Gregory’s pontificate. For more in depth considerations see also:Straw, Carole. Gregory the Great: Perfection in Imperfection, Berkeley, Los Angeles and London, University of California Press, 1988.Demacopoulos, George E. Gregory the Great: Ascetic, Pastor and First Man of Rome, Notre Dame, Indiana, University of Notre Dame Press, 2015.

- A discussion of this work by Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank can be found at: https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-americas/new-spain/viceroyalty-new-spain/a/featherworks-the-mass-of-st-gregory and at the Metropolitan Museum website: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/722118

,%20c.%201515-1520_New%20York,%20Pierpont_MS%20M%201166,%20fol.%2051r.jpg)

,%20c.%201411-1416_Chantilly,%20Musee%20Conde_MS%2065,%20fol.%2072r.jpg)

,%20c.%201411-1416_Chantilly,%20Musee%20Conde_MS%2065,%20fol.%2071v.jpg)

,%20c.%201445-1465_New%20York,%20Pierpont_MS%20M%20673,%20fol.%20255r.jpg)

,%20c.%201525-1530_New%20York,%20Pierpont_Ms%20M%201175,%20fol.%20202v.jpg)

,%201348_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Francais%20241,%20fol.%20122v.jpg)

,%20c.%201325-1350_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Francais%20185,%20fol.%20182v.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment