|

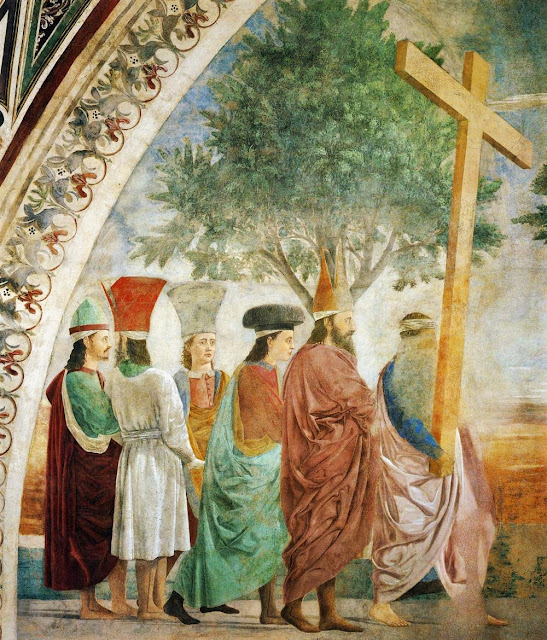

| Piero della Francesca, Detail of Exaltation of the Holy Cross Italian, c. 1452-1466 Arezzo, Church of San Francesco |

"Jesus said to Nicodemus:

"No one has gone up to heaven

except the one who has come down from heaven, the Son of Man.

And just as Moses lifted up the serpent in the desert,

so must the Son of Man be lifted up,

so that everyone who believes in him may have eternal life."

(John 3:13-15, Gospel reading for the feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross)

"No one has gone up to heaven

except the one who has come down from heaven, the Son of Man.

And just as Moses lifted up the serpent in the desert,

so must the Son of Man be lifted up,

so that everyone who believes in him may have eternal life."

(John 3:13-15, Gospel reading for the feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross)

This “lifting up” of the Son of Man was accomplished through the cross. And as stated by Fr. Richard Viladesau, currently Professor of Theology at Fordham University, in his book The Beauty of the Cross: the Passion of Christ In Theology and the Arts, from the Catacombs to the Eve of the Renaissance, “From its earliest times, Christianity was distinguished as being religio crucis – the religion of the cross. The cross has always been its most obvious and universal symbol; and in the contemporary world, we are once again reminded that it is the cross and its meaning that set Christianity apart from other world religions.” Fr. Viladesau goes on to discuss the ways in which the cross of Christ continues to be “a stumbling block and foolishness” (1 Corinthians 1:23), viewed with horror and mistrust by non-Christians and post-Christians. 1

The history and legends surrounding the Cross are extensive and far reaching in scope. However, the feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross on September 14 focuses on two documented events in the history of the True Cross.

The first is the dedication of the basilica of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem on September 14, 335. Built, by order of the Emperor Constantine, on top of the remains of Golgotha and the nearby burial place of Jesus, the basilica replaced the Roman temple of Venus that had been built atop them during the reign of Hadrian, approximately 100 years earlier.

The second is the Exaltation (or Triumph) of the Cross, when the Byzantine Emperor, Heraclius, returned the relic of the True Cross to Jerusalem in 628. It had been captured fourteen years earlier by the forces of the Sassanian Emperor of Persia, Chosroes II, as part of the long drawn out war between Persia and Byzantium that exhausted both empires and opened their territories up to eventual defeat by the armies of Islam in the later part of the 7th century. Heraclius deliberately scheduled this event for September 14th to tie it to the earlier, Constantinian event.

These real events not only formed the basis for the liturgical feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross they also became part of the iconography of the Legend of the True Cross. This iconography includes the actual events described above, mixed with folk legends and Old Testament typology. It consists of three distinct parts: The Finding and Proving of the True Cross, the Exaltation of the Holy Cross and the Legend of the Tree of Life (the Lignum vitae).2

The history and legends surrounding the Cross are extensive and far reaching in scope. However, the feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross on September 14 focuses on two documented events in the history of the True Cross.

The first is the dedication of the basilica of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem on September 14, 335. Built, by order of the Emperor Constantine, on top of the remains of Golgotha and the nearby burial place of Jesus, the basilica replaced the Roman temple of Venus that had been built atop them during the reign of Hadrian, approximately 100 years earlier.

The second is the Exaltation (or Triumph) of the Cross, when the Byzantine Emperor, Heraclius, returned the relic of the True Cross to Jerusalem in 628. It had been captured fourteen years earlier by the forces of the Sassanian Emperor of Persia, Chosroes II, as part of the long drawn out war between Persia and Byzantium that exhausted both empires and opened their territories up to eventual defeat by the armies of Islam in the later part of the 7th century. Heraclius deliberately scheduled this event for September 14th to tie it to the earlier, Constantinian event.

These real events not only formed the basis for the liturgical feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross they also became part of the iconography of the Legend of the True Cross. This iconography includes the actual events described above, mixed with folk legends and Old Testament typology. It consists of three distinct parts: The Finding and Proving of the True Cross, the Exaltation of the Holy Cross and the Legend of the Tree of Life (the Lignum vitae).2

The iconography of the True Cross has its most complete and notable example in the work done by the Quattrocento master, Piero della Francesca, in the church of San Francesco in Arezzo. This cycle of paintings brings together all three strands listed above.

The Finding and Proving of the True Cross

The Finding and Proving of the True Cross combines elements of actual history with folk legends. It is known from documentary evidence that excavations at Jerusalem following Constantine’s acceptance of Christianity had located the sites of the Crucifixion and Resurrection underneath the temple of Venus and that this had resulted in the construction of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, dedicated in 335.

It is also known from documentary evidence that by at least the year 340 AD a fragment of the Cross was being exhibited to pilgrims in Jerusalem. There is a very detailed account of this event in a letter recording the pilgrimage to Jerusalem of the nun, Egeria, dating from about 380 AD.

The first mention of Saint Helena, mother of Constantine, in connection with the finding of the Cross is a mention by Saint Ambrose in a funeral oration on the death of the Emperor Theodosius I in 395. 3 It is known that she was in the Holy Land, visiting sites associated with the life of Christ, during the later half of the 320s and that her Roman palace became the site of the church of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme (Holy Cross in Jerusalem) where fragments of the True Cross and other possible relics are preserved. But whether Helena was instrumental in finding the Cross or whether she was even there at that exact time is open to dispute. What is not open to dispute is that by the middle of the 4th century elements of what was believed to be the True Cross were displayed on particular feast days in Jerusalem and that by the end of the 4th century fragments of this relic were being distributed to other churches throughout the Christian world. On this historical base were woven a series of legends and poetic extrapolations from the Old and New Testament.

The Legend of the Tree of Life

The Legend of the Tree of Life is such a development from biblical typology. First stated by St. Paul in 1 Corinthians 15:22, the typological thought runs that: just as Adam is the first man, the first to disobey God’s commands and the first to bring death into the world, so Christ is the new Adam, a sinless sacrifice in accordance with His Father’s will, whose death brings eternal life.

In the legend, the Archangel Michael gives a seedling of the Tree of Life from the Garden of Eden to Seth, one of Adam's sons. Michael instructs Seth to place the seedlings in Adam’s mouth before his burial and, when his father dies, Seth complies. This seedling grows into the tree from whose wood the Cross would eventually be made.

Having grown for many years the tree dies in the time of King Solomon and its wood is made into planks for a bridge. On her journey to visit Solomon, the Queen of Sheba comes upon the bridge and, in a flash of revelation, recognizes that it will bear the Savior of the World. She kneels before it in adoration. On her arrival at Solomon’s court, she tells him that his glory will be diminished by his descendant, who will hang on a cross made from the wood of the bridge.

In order to prevent this from happening, Solomon orders that the wood be drowned at the bottom of a well. But in the time of Jesus it is found and removed just in time to be made into the Cross.

|

| Piero della Francesca, Burial of the Wood Italian, c. 1452-1466 Arezzo, Church of San Francesco |

The Exaltation of the True Cross

The Exaltation of the Cross is a real event (see above) but, as recounted by Jacobus de Voragine in the Golden Legend (ca. 1260), has added elements that make it read like a medieval romance.4

|

| Pier della Francesca, Exaltation of the Holy Cross Italian, c. 1452-1466 Arezzo, Church of San Francesco |

The Legend and Piero della Francesca at Arezzo

Although there are individual works of art that touch on parts of the Legend, there are also a number of cycles of monumental church decoration focusing on the legend. The greatest of these is the cycle by Piero della Francesca in the church of San Francesco in Arezzo, located in Tuscany, between Florence and Rome.

|

| Overview of the Chapel of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross Italian, c. 1452-1466 Arezzo, Church of San Francesco |

Much ink has been spilled over this particular fresco cycle. It was painted sometime between 1452 and 1466, the specific dates being unknown as there is no known written documentation. The time frame is presumed from documents that establish that it was not in existence in 1452 and was finished in 1466. The church of San Francesco in Arezzo is a Franciscan foundation and there is a history of this subject matter in Franciscan churches.5

The chapel in which the cycle is placed was the donation of the Bacci family and it is they who paid for the cycle, although the Franciscans probably advised, or perhaps even dictated, the subject matter. The cycle includes episodes from the Legend, beginning with the death of Adam and the placing of the seeds of Tree of Life in his mouth by his son, Seth.

The scenes in the cycle are not arranged as a continuous narrative. Instead they are shown in related pairs, positioned across the width of the room from each other. Thus the beginning and ending of the cycle, the Death of Adam and the final Exaltation of the Holy Cross by Heraclius are positioned at the top of their respective, facing walls.

In the middle tier, the interventions of the two queens, Helena and Sheba, face each other.

At the bottom, we see two small pictures of miraculous annunciations. The first is the annunciation to Mary that resulted in the birth of Jesus the Savior,

The scenes in the cycle are not arranged as a continuous narrative. Instead they are shown in related pairs, positioned across the width of the room from each other. Thus the beginning and ending of the cycle, the Death of Adam and the final Exaltation of the Holy Cross by Heraclius are positioned at the top of their respective, facing walls.

In the middle tier, the interventions of the two queens, Helena and Sheba, face each other.

At the bottom, we see two small pictures of miraculous annunciations. The first is the annunciation to Mary that resulted in the birth of Jesus the Savior,

|

Piero della Francesca, Annunciation Italian, c. 1452-1466 Arezzo, Church of San Francesco |

The second is the annunciation of the Cross as a symbol of victory in a dream of Constantine. This resulted in the conversion of Constantine, his victory over Maxentius and the eventual acceptance of Christianity by the Roman Empire.

|

Piero della Francesca, Vision of Constantine Italian, c. 1452-1466 Arezzo, Church of San Francesco |

Beside them, on the long walls, are two large battle scenes (that of Constantine over his rival Maxentius and that of Heraclius over Chosroes II).

|

| Piero della Francesca, Victory of Constantine over Maxentius Italian, c. 1452-1466 Arezzo, Church of San Francesco |

While difficult to see in the picture above, the association of this battle not only with the sign of the cross, but with the form of the Holy Cross itself, is made explicit when one looks at the detail of what Constantine is holding in his outstretched hand.

.jpg) |

| Piero della Francesca, Victory of Constantine over Maxentius (detail) Italian, c. 1452-1466 Arezzo, Church of San Francesco |

|

| Piero della Francesca, Victory of Heraclius over Chosroes II Italian, c. 1452-1466 Arezzo, Church of San Francesco |

Piero’s solid, rounded figures and geometrically arranged spaces produce an effect of almost dreamlike activity. They seem almost doll-like, as they stare gravely with open eyes into space or toward heaven or with adoring intensity at the Cross.

|

| Piero della Francesca, Detail from The Queen of Sheba Venerates the Wood and Meets with Solomon Italian, c. 1452-1466 Arezzo, Church of San Francesco |

|

| Piero della Francesca, Detail from Finding and Proving of the True Cross Italian, c. 1452-1455 Arezzo, Church of San Francesco |

|

Piero della Francesca, Detail from Exaltation of the Holy Cross Italian, c. 1452-1466 Arezzo, Church of San Francesco |

Even when they are gathered into conversational groups it is difficult to imagine that they are actually talking.

|

Piero della Francesca, Detail from Meeting of Solomon and Sheba Italian, c. 1452-1466 Arezzo, Church of San Francesco |

|

Piero della Francesca, Detail from Meeting of Solomon and Sheba Italian, c. 1452-1466 Arezzo, Church of San Francesco |

Even the battle scenes appear to take place in an atmosphere of extreme quiet, as though all the figures were holding their breath, even as they act. Each person seems wrapped in his or her own meditation. They do not even react to injury.

|

| Piero della Francesca, Deatail from Battle of Heraclius Italian, c. 1452-1466 Arezzo, Church of San Francesco |

|

| Piero della Francesca, Deatail from Battle of Heraclius Italian, c. 1452-1466 Arezzo, Church of San Francesco |

|

| Piero della Francesca, Deatail from Battle of Heraclius Italian, c. 1452-1466 Arezzo, Church of San Francesco |

Born in the small Tuscan town of Borgo San Sepolcro, Piero learned his craft as a painter in Florence in the workshop of Domenico Veneziano. This was during the period in the mid-15th century when Florentine painters were learning to manipulate the principles of the new found technique of perspective and Piero became deeply involved in the development. In later life, he wrote treatises on mathematics, geometry and perspective. This study is reflected in the perspective that is evident in his True Cross cycle of paintings in Arezzo. He was also a student of the effects of light passing over solid objects. This is most obvious in the fresco of “The Dream of Constantine” which studies the effect of light in a nighttime scene. But it is also found throughout the cycle.

|

Piero della Francesca, Detail from the Vision of Constantine Italian, c. 1452-1466 Arezzo, Church of San Francesco |

|

Piero della Francesca, Detail from the Vision of Constantine Italian, c. 1452-1466 Arezzo, Church of San Francesco |

This cycle, therefore, stands at a special point in the history of Renaissance art, the point at which artists have begun to assimilate the use of perspective and the effects of light, but have not yet mastered these tools. Piero’s work points the way to Raphael, Caravaggio and Vermeer.

© M. Duffy, 2011, pictures revised and new material added 2022

_______________________________________________

1. Viladesau, Richard. The Beauty of the Cross: the Passion of Christ In Theology and the Arts, from the Catacombs to the Eve of the Renaissance, Oxford and New York, 2006, pp. 7-9. Some sections are available on the internet at: http://books.google.com/books?id=cTFh4tm9cMwC&printsec=frontcover&dq=richard+viladesau&hl=en&ei=tE9xTqLCEabF0AH4mvixCg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=5&ved=0CEQQ6AEwBA#v=onepage&q&f=false

See also his The Triumph of the Cross: the Passion of Christ in Theology and the Arts, from the Renaissance to the Counter-Reformation, Oxford and New York, 2008. Some sections of this book are also available at: http://books.google.com/books?id=3K_RKPz94nAC&printsec=frontcover&dq=richard+viladesau&hl=en&ei=tE9xTqLCEabF0AH4mvixCg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CDUQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q&f=false

2. Baert, Barbara. A Heritage of Holy Wood: The Legend of the True Cross in Text and Image, Leiden, Koninklijke Brill, NV, 2004, p. 1. Some sections are available on the internet at: http://books.google.com/books?id=vVcRd2sldBIC&printsec=frontcover&dq=barbara+baert&hl=en&ei=vlJxTvy_M4rj0QH7nezfBg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CDsQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q&f=false

3. Baert, p. 2.

4. The Golden Legend or Lives of the Saints. Compiled by Jacobus de Voragine, Archbishop of Genoa, 1275. First Edition Published 1470. Englished by William Caxton, First Edition 1483, Edited by F.S. Ellis, Temple Classics, 1900 (Reprinted 1922, 1931.), Vol. 5, pages 60-65. It can be accessed on the internet at http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/basis/goldenlegend/GoldenLegend-Volume5.asp#Exaltation of the Holy Cross.

5. Baert, p. 11-12. Also, Lavin, Marilyn Aronberg in Piero della Francesca: The Legend of the True Cross in the Church of San Francesco in Arezzo, Ed. Anna Maria Maetzke and Carolo Bertelli. Milan, Skira editore, 2001, pp. 27-37.