|

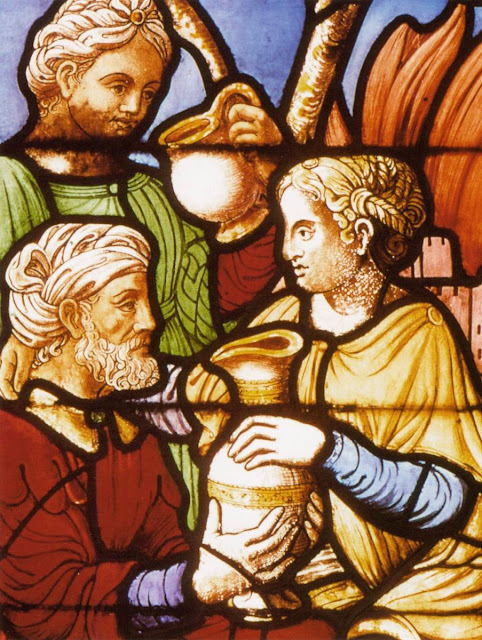

| The De Roos Factory, Jesus Meets Zacchaeus Dutch (Delft), c. 1690-1710 London, Victoria and Albert Museum |

“At that time, Jesus came to Jericho and intended to pass through the town.

Now a man there named Zacchaeus,

who was a chief tax collector and

also a wealthy man,

was seeking to see who Jesus was;

but he could not see him because

of the crowd,

for he was short in stature.

So he ran ahead and climbed a

sycamore tree in order to see Jesus,

who was about to pass that way.

When he reached the place, Jesus

looked up and said,

“Zacchaeus, come down quickly,

for today I must stay at your

house.”

And he came down quickly and

received him with joy.

When they all saw this, they

began to grumble, saying,

“He has gone to stay at the house

of a sinner.”

But Zacchaeus stood there and

said to the Lord,

“Behold, half of my possessions,

Lord, I shall give to the poor,

and if I have extorted anything

from anyone

I shall repay it four times

over.”

And Jesus said to him,

“Today salvation has come to this

house

because this man too is a

descendant of Abraham.

For the Son of Man has come to

seek

and to save what was lost.”

Luke 19:1-10

Gospel for the Thirty-first Sunday in Ordinary Time, Year C, October

30, 2022

This story, found only in the Gospel of Luke, is as full of important

meaning as any other portion of the Gospel accounts of the ministry of Jesus

between His baptism and His passion. On

one level it is a human, even a humorous story, on the other hand it is

profound.

|

| Pietro Monaco after Bernardo Strozzi, Jesus Encounters Zacchaeus Italian (Venice), 1730-1739 London, British Museum |

The action of this story takes place in Luke, as Jesus is traveling up

to Jerusalem, where He will be put to death.

It is set as He is about to enter the town of Jericho, one of the oldest

continuously lived in sites in the world.

A resident of Jericho named Zacchaeus approaches the crowd awaiting the

entry of Jesus out of curiosity. He is

short, so he decides to climb a tree to get a better view. But, instead of him getting a look at Jesus,

it is Jesus who sees him and, it seems, sees into him, for He knows him

and calls him by name. More than that, Jesus

tells him that He will stay in his house.

Instead of being upset at this unexpected turn of events Zacchaeus

welcomes Him, receiving Him “with joy”.

When unspecified people (? residents of Jericho, the apostles,

Pharisees?) grumble about Jesus’ dining with a “sinner” Zacchaeus makes a

stunning statement “Behold, half of my possessions, Lord, I shall give to the

poor, and if I have extorted anything from anyone I shall repay it four times

over.” (Luke 19:8) Jesus then tells him that “Today salvation has come to this

house because this man too is a descendant of Abraham. For the Son of Man has come to seek and to

save what was lost.” (Luke 19:9-10)

|

| Boetius Adamszoon Bolswert, Christ in the House of Zacchaeus Flemish, 1590-1622 Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum |

It would seem that this small story contains quite a bit of meaning. For, Zacchaeus is a kind of “everyman” (or perhaps, nowadays, “every person”), a stand in for all of us. He is curious about this celebrity who is coming to town and struggles to get a better view. But, what he gets from this particular celebrity is unexpected. He gets a calling, a personal invitation, to come down and welcome the visitor into his house. And, instead of shying away, of saying “no thanks, my house isn’t ready” Zacchaeus “receives Him with joy”. Furthermore, so affected is he by the meeting, he offers to give one half of all he owns to the poor (and we are told he was a wealthy man, so it’s not a small thing). And, not content with that, he offers to repay anyone he has extorted money from four times over. Since, the way in which tax collectors went about getting the money they were required to raise was through extortion, this probably represented a substantial amount. Roman provincial tax collectors were permitted to keep a portion of the money they raised for the Imperial treasury. This which meant that, in order to make the money they felt they were entitled to, above that required by the Roman government, the sums they extracted from people were pretty large and burdensome, and deeply resented. By making this offer Zacchaeus is acknowledging his guilt, as well as offering to pay restitution.

The ways in which artists illustrated this story through time is an

interesting chronicle, with some divergent branches and shifts of focus.

To begin with, early illustrations told a fairly simple tale. Two illuminations in royal books painted in the scriptorium of Reichenau around the beginning of the 11th century provide two different views of the same story, one of which would lead to a branch development a few centuries later. One shows Jesus, seated on a donkey, entering Jericho. In the other book, Jesus is on foot, surrounded by His disciples. The latter image also includes the feast at the house of Zacchaeus.

|

| Jesus Encounters Zacchaeus as He Enters Jericho From the Gospel Book of Otto III German (Reichenau), c.1000 Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek MS Clm 4453, fol. 234v |

|

| Jesus Encounters Zacchaeus and Dines at His House From the Gospel Book of Heinrich II German (Reichenau), ca.1007-1012 Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek MS Clm 4452, fol. 200r |

A few decades later, the image was incorporated on the bronze column of Bishop Bernward in Hildesheim, one of the great bronze works that Bernward commissioned that revived the art of bronze casting, after its post-Roman decline.

|

| Jesus Encounters Zacchaeus Detail of Berward's Column German (Hildesheim), ca. 1020 Hildesheim, Cathedral |

For the next two hundred plus years, illustrations of the text were fairly simple and straightforward.

,%20c.%201100-1150_Cambrai,%20Bibliotheque%20municipale_MS%20528.jpg) |

| Christ Addressing Zacchaeus From a Book of Homilies French (Cambrai), c. 1100-1150 Cambrai, Bibliotheque municipale MS 528 |

|

| Jesus Encounters Zacchaeus From the Book of Pericopes of the Monastery of Saint Erentrud Austrian (Salzburg), 1140 Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek MS Cod. lat.15903, fol. 96v |

|

Jesus Encounters Zacchaeus From a Gospel Book German (Passau), ca. 1170-1180 Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek MS Clm 16002, fol. 40r |

This image cleverly uses initials to represent the tree and Jesus standing on the ground.

,%20c.%201170-1180_Los%20Angeles,%20J.%20Paul%20Gerry%20Museum_MS%2064,%20fol.%20164r.jpg) |

| Initial D Containing the Encounter Between Jesus and Zacchaeus From the Stammheim Missal German (Hildesheim), c. 1170-1180 Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum MS 64, fol. 164r |

|

| Jesus Encounters Zacchaeus from a Picture Bible French (St. Omer, Abbey of St. Bertin), ca.1190-1200 The Hague, Koninklijk Bibliotheek MS KB 76 F 5, fol. 013r |

|

| Jesus Encounters Zacchaeus From a Picture Bible Navarrese, c. 1197 Amiens, Bibliotheque municipale MS 108 |

| |

|

|

| Jesus Encounters Zacchaeus and Dines with Him North German (Monastery of Weinhausen), ca. 1335 Weinhausen, Weinhausen Abbey |

|

| Jesus Encounters Zacchaeus From a 13th Century Pattern Book German, 1200-1300 Freiburg im Breisgau, Augustiner Museum G23.1c |

Around the beginning of the 14th century, the image, propagated throughout Europe by such means as pattern books and the interchange of artists, merged into a different part of the Gospel story, the triumphal entry of Jesus into Jerusalem on what we now call Palm Sunday.

Artists began to incorporate one or two or more people in trees in their illustrations of the entry. And this confusion between the story of Zacchaeus and Jesus’ entry into Jericho and Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem lasted for about 100 years.

|

Giotto, Entry into Jerusalem Italian, c. 1300-1305 Padua, Arena/Scrovegni Chapel |

|

| Duccio, Entry into Jerusalem From the Maestà Altarpiece Italian, c. 1308-1311 Siena, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo |

|

| Pietro Lorenzetti. Entry into Jerusalem Italian, c. 1320 Assisi, Church of San Francesco, Lower Church |

|

German Master, Entry into Jerusalem Detail from the Osnabrück Altarpiece German, c. 1370s Cologne, Wallraf-Richartz-Museum |

|

The Limbourg Brothers (Herman, Jean and Paul), Jesus Enters Jerusalem From the Tres Riches Heures of the Duc de Berry Dutch, c. 1412-1416 Chantilly, Musée Condé MS 65, fol. 173v |

However, early in the 15th century, the images became unwound once again. The emphasis again returned to the dramatic moment of the meeting between Jesus and the small man in the tree.

| |

|

,%20c.%201475=1500_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Francais%20178,%20fol.%2089v.jpg) |

| Jean Colcombe, Jesus Encounters Zacchaeus From Vita Jesu Christi by Ludolf of Saxony French (Bourges), c. 1475=1500 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 178, fol. 89v |

,%20c.%201490s_London,%20Victoria%20and%20Albert%20Museum.jpg) |

| Jesus Encounters Zacchaeus Cutting from a Choir Book German (Rheinland-Pfalz), c. 1490s London, Victoria and Albert Museum |

|

| Anonymous, Jesus Encounters Zacchaeus A Cutting from a Gradual Book Dutch, ea. 16th Century London, Victoria and Albert Museum |

As manuscripts were replaced by printed books, painting of Biblical scenes was no longer practiced in easily transportable miniature form. Therefore, it is through the medium of prints and other of the “minor” arts that the images were transmitted. This made them much more available to the ordinary person, since prints are cheaper than precious manuscripts and more mobile than wall paintings.

|

| Delft Master, Meal at House of Zacchaeus and the Encounter of Jesus and Zacchaeus Dutch, c. 1480-1500 Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum |

|

| Antwerp Master, Meal at the House of Zacchaeus and the Encounter of Jesus and Zacchaeus Flemish, c. 1485-1491 Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum |

|

| Glass Roundel with the Encounter of Jesus and Zacchaeus Dutch, c. 1500-1510 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Cloisters Collection |

|

| Glass Roundel, Jesus at Supper in the house of Zacchaeus German, c.1530 London, Victoria and Albert Museum |

|

| Anonymous, Encounter of Jesus and Zacchaeus Dutch, 1536 Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum |

As time passed more figures began to be included. In addition to all the apostles there were townspeople, including women and children.

|

| Philips Galle after Maerten de Vos, Encounter of Jesus and Zacchaeus Flemish, c. 1547-1612 Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum |

|

| Erasmus Quellinus the Younger, Jesus Encounters Zacchaeus (and most of Jericho) Flemish, 1660 Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum |

|

| Possibly Jan Luyken, Jesus Encounters Zacchaeus Dutch, 1660-1712 Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum |

|

| Alexandre Ubelesqui, Encounter of Jesus and Zacchaeus at Jericho French, c.1700 Paris, Musée du Louvre, Département des arts graphiques |

|

| Glazed Tile, Jesus Encounters Zacchaeus English or Dutch, ca.1718-1725 London, Victoria and Albert Museum |

Paintings from the Renaissance, Baroque and Rococo periods are infrequent, as are representations in sculpture. They do, however, exist.

|

| Jacopo Palma il Giovane, Christ Calling Zacchaeus Italian, c. 1575 Cambridge, University of Cambridge Museums, Fitzwilliam Museum |

|

Bernardo Strozzi, Encounter of Jesus and Zacchaeus Italian, c.1640 Nantes, Musée des Beaux-Arts |

|

Domenico Tiepolo, Christ in the House of Zacchaeus in Jericho Italian, ca.1750-1800 Paris, Musée du Louvre |

|

| Joseph Anton Feuchtmayer, Encounter of Jesus with Zacchaeus Austrian, 1761-1763 Sankt Gallen, Cathedral |

|

| Thomas Schaidhauf, Encounter of Jesus and Zacchaeus German, c. 1780-1807 Furstenfeldbruck, Catholic Parish of St. Bernard |

There was one significant further development on the theme, that of Zacchaeus as a penitent, detached from the meeting with Jesus or His reception in Zacchaeus’ home. In these Zacchaeus is very clearly offering his ill-gotten gains to Jesus or is repenting in private prayer.

|

| Boetius Adamszoon Bolswert, Christ in the House of Zacchaeus Flemish, c. 1590-1622 Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum |

|

| Willem Isaacszoon van Swanenburg after Abraham Bloemaert, Penitent Zacchaeus From a series of prints of Penitents Dutch, 1611 Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum |

A further interesting image of Zacchaeus, showing him climbing the tree, preparatory to the arrival of Jesus, is found in the book Predigen teütsch (German Preaching), by the preacher Johann Geiler von Keysersberg (1445-1510), who was a popular preacher at the end of the 15th century.1

_by%20Johann%20Geiler%20von%20Kaisersberg_German_1508-10_BM.jpg) |

Hans Burgkmair the Elder, Zacchaeus Climbs the Tree of Faith, Hope and Charity From Predigen teütsch by Johann Geiler von Keysersberg German, c. 1508-1510 London, British Museum |

It shows the figure of Zacchaeus climbing a tree (incorrectly shown as a palm). The tree is wrapped in a banderol with the words “Leibe”, “Hoffnung” and “Glaub”(sic), which translate as Love, Hope and Faith. Someone has handwritten in the Latin translations of these words: “Charitas”, “Spes” and “Fides”. In other words, Faith, Hope and Charity, the three theological virtues. Zacchaeus is here shown for what he represents, the person who seeks to find salvation through Christ and the church.

©

M. Duffy, 2016, revised and expanded 2022.

1. Scheid, Nikolaus. "Johann Geiler von

Kaysersberg." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 6. New York: Robert

Appleton Company, 1909. 28 Oct. 2016 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/06403c.htm>.

Scripture texts in this work are taken from the New

American Bible, revised edition © 2010, 1991, 1986, 1970 Confraternity of

Christian Doctrine, Washington, D.C. and are used by permission of the

copyright owner. All Rights Reserved. No part of the New American Bible may be

reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the copyright owner.

,%20c.%20879=882_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Grec%20510,%20fol.%2087v_detail.jpg)

,%20c.%201420-1422+Lon,%20Brirtish%20Library_MS%20Royal%2020%20B%20IV,%20fol.%2094r.jpg)

,%201577_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Rothschild%203070,%20fol.%20206r.jpg)