|

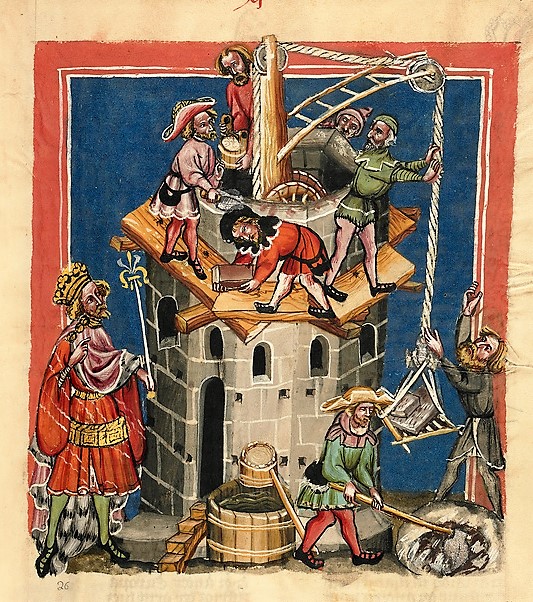

| Nimrod Commands the Building of the Tower of Babel from Weltchronik German (Regensburg), 1355-1365 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M769, fol.28v |

“The whole world spoke the same language,

using the same words.

While the people were migrating in the east,

they came upon a valley in the land of

Shinar and settled there.

They said to one another,

"Come, let us mold bricks and harden

them with fire."

They used bricks for stone, and bitumen for

mortar.

Then they said, "Come, let us build

ourselves a city

and a tower with its top in the sky,

and so make a name for ourselves;

otherwise we shall be scattered all over the

earth."

The LORD came down to see the city and the

tower

that they had built.

Then the LORD said: "If now, while they

are one people,

all speaking the same language,

they have started to do this,

nothing will later stop them from doing whatever

they presume to do.

Let us then go down and there confuse their

language,

so that one will not understand what another

says."

Thus the LORD scattered them from there all

over the earth,

and they stopped building the city.

That is why it was called Babel,

because there the LORD confused the speech

of all the world.

It was from that place that he scattered

them all over the earth.”

Genesis

11:1-9, Reading for February 17, 2017, Weekday Readings Cycle 1

During this

month of February in Weekday Cycle 1, which is being read at all the weekday

Masses this year, we are presented with readings from the first book of the Old

Testament, the book of Genesis.

One of the

stories about the beginnings of human awareness of God is the story of the

Tower of Babel. We are told that “once

upon a time” all the people living on earth spoke one language. This is actually probably true, since at one

time, the human population of the earth was tiny and all its members probably

did make the same sounds to signify the same things. Recent scientific research has concluded that

all of us are the children of a small group of African primates and that there

really was a biological Adam and a biological Eve whose DNA every human being

alive still carries. In 2011 a flurry of

scientific publications posited that there was also evidence for an original

language common to all humans at one point in time in Africa that was the

“mother language” for all modern languages. 1

|

| Jan Collaert after Jan Snellinck, Nimrod and the People Laying Out the Site for the Tower of Babel from Thesaurus sacrarum historiarum veteris testamenti Flemish, c.1579 London, British Museum |

Frederik van Valckenborgh I, Building of the Tower of Babel

Dutch, End of the 16th-Beginning of the 17th Centuries

Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum

|

The idea of

the building of such a tower probably comes from memories of the ziggurats of

ancient Mesopotamia, the land between the two rivers, in which Abraham was

living when first called by God to move west into Canaan.

|

| Reconstruction of a Sumerian Ziggurat |

All of the earliest known urban civilizations,

with the exception of Egypt, arose in this area: Sumer, Babylon, Assyria and others and they

built ziggurats. A ziggurat was a sort

of pyramidal shaped building, made of brick, with terraces that defined each of

the levels as it ascended, somewhat like a square wedding cake. The different levels were connected by

exterior stairs, resulting in a zig-zag pattern. At the top archaeologists believe that there was

probably a shrine to the local gods, though none of these has survived.

In the

Biblical narrative, it is said that “while the people were migrating in the

east, they came upon a valley in the land of Shinar and settled there”, which

is a rather remarkable statement. It is

believed by evolutionary anthropologists that modern humans migrated out of

Africa in several waves, including one that went toward the lands of Mesopotamia. The text would seem to be a retained record

of an eastward migration at a very early time.

Shinar is the Biblical name for “the land of ancient Babylonia,

embracing Sumer and Akkad, present-day southern Iraq”2 ruled at the

time of the building of the tower by Nimrud, a mighty hunter, according to

Genesis 10:8-12. 3

|

| Leandro Bassano, Building of the Tower of Babel Italian, c. 1600 London, National Gallery |

The Biblical

account is, among other interpretations, a way of explaining how the land of

Babylon got its name. The notes on this

chapter in the New American Bible explain that Babel is “the Hebrew form of the name “Babylon”; the

Babylonians interpreted their name for the city, Bab-ili, as “gate

of god.” The Hebrew word balal, “he confused,” has a similar sound.” Accordingly, the Biblical account says that

when the people had settled in the land of Shinar they decided to build a city

and a great tower, which caused concern to God.

Why God should be so upset by this tower is not stated. But, what is stated seems to suggest that, by

wishing to create this tower and city, the people appear to be colluding in

setting themselves up to rival God, “to be like gods” as the snake had tempted

Adam and Eve (Genesis 3:5). In addition,

by wishing to concentrate in the city they are refusing to move out to populate

the earth, as God had instructed at the end of the Flood “Be fertile and

multiply and fill the earth” (Genesis 9:1 and 7). Furthermore, it demonstrated an astonishing

level of human pride, especially as it came shortly after the great Flood and showed the continuing force of Original Sin. So, to

discourage them from further aggrandizing efforts and to achieve His

commandment, He caused them to begin to speak differing languages, which

resulted in their not being able to complete the building and into dispersing

in different language groups all over the earth.5

The Tower of Babel has been a subject that has fascinated artists as they attempted to imagine

what this tower would be like.

But where

did European artists find the models for their idea of what this tower should

look like, since there were no ziggurats in Europe at any time and knowledge of them, if it ever existed in Europe, had been forgotten?

Models of the Tower

Artists in

Europe would have had three structures readily available to them that could be

models for such a tower: the castle

tower, the church bell tower and the city gate tower. And, not surprisingly, these are what we

see during the middle ages and early portion of the Renaissance.

|

| Ivory Relief, The Drunkeness of Noah and Building the Tower of Babel Italian, 11th Century Salerno, Museo Diocesano San Matteo |

|

| Mosaic of the Building of the Tower of Babel Italian, 1140-1170 Palermo, Cappella Palatina |

|

| Mosaic of the Building of the Tower of Babel Italian, 1180s Monreale, Cathedral |

We are also

shown, through these images, some of the building techniques by which the great

achievements of medieval and Renaissance architecture were created.

|

| Building the Tower of Babel from The Huntingfield Psalter Anglo-Norman (Oxford), 1212-1220_ New York, Pierpoint Morgan Library MS M43, fol. 9v |

|

| Building the Tower of Babel from Old Testament Miniatures French (Paris), 1244-1254 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M638, fol.3ra |

|

| Building the Tower of Babel from Bible historiale by Guiard des Moulins French (Paris), c. 1300-1325 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 160, fol. 17v |

|

| Building the Tower of Babel from Roman de toute chevalerie by Thomas of Kent English (London), c. 1308-1312 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 24364, fol. 79 |

|

| Master of the Roman de Fauvel, Building the Tower of Babel from Bible historiale by Guiard des Moulins French (Paris), c. 1320-1340 The Hague, Koninklijk Bibliothek MS KB 71 A 23, fol. 16r |

|

| Building the Tower of Babel from The Golden Haggadah. Haggadah for Passover Spanish (Catalonia), c. 1325-1350 London, British Library MS Additional 27210, fol. 3 |

|

| Michiel van der Borch, Building the Tower of Babel from Rhimebible by Jacob van Maerlant Dutch (Utrecht), 1332 The Hague, Museum Meermano MS MMW 10 B 21, fol. 9v |

|

| Master of the Roman de Fauvel, Building the Tower of Babel from Specululm historiale by Vincent of Beauvais French (Paris), 1333-1334 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 316, fol. 49v |

|

| Egerton Master, Building the Tower of Babel from Egerton Genesis Picture Book English (Norwich or Durham), c. 1350-1375 London, British Library MS Egerton 1894, fol. 5v |

|

| Building the Tower of Babel from Histoire ancienne jusqu'a Cesar French (Paris), c. 1375-1400 London, British Library MS Additional 25884, fol. 80v |

|

| Building the Tower of Babel from De Civitate Dei by Augustine of Hippo French (Paris), c. 1400 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 21, fol. 87 |

|

| Rohan Master and Collaborators, Building the Tower of Babel from De Casibus by Boccaccio French (Paris), 1400-1425 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 226, fol. 8v |

|

| Building the Tower of Babel from Weltchronik German (Regensburg), c. 1400-1410 Los Angelse, J. Paul Gerry Museum MS 33, fol. 13 |

|

| Building the Towr of Babel from De Casibus by Boccaccio French (Western France), c. 1425-1450 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 232, fol. 5 |

|

| Building the Tower of Babel from a Genealogical and Chronicle Roll French (North), 1470-1480 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M1157, fol. 15 |

|

| Building the Tower of Babel Belgian (Bruges), ca. 1490 Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum |

|

| Hieronymus Bosch, The Tower of Babel Right Wing of Triptych of the Haywain Dutch, 1500-1502 Madrid, Museo del Prado |

From the mid-fourteenth century it is probably safe to say that we begin to see traces of one of the most famous of all church bell towers, the one then being completed at Pisa, now known as the Leaning Tower of Pisa. Its colonnaded tiers can be traced in many of the illustrations of the story of the Tower of Babel in the coming years.

|

Building the Tower of Babel

from Histoire ancienne jusqu'a Cesar

Franch (Paris), c. 1390

Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France

MS Francais 250, fol. 19

|

|

Nimrod Oversees the Building of the Tower of Babel

from De Civitate Dei by St. Augustine of Hippo

French (Paris), ca. 1400

Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France

MS Francais 23, fol. 119v

|

|

Master of Jacques d'Armagnac, Building the Tower of Babel

from La Bouquechardiere by Jean de Courcy

French (Rouen), Before 1476

The Hague, Meermano Museum

MS MMW 10 A 17, fol. 184r

|

As the

Renaissance matured, another model became more popular as interest in antiquity

increased. This was the famous Pharos,

the lighthouse of Alexandria, which was one of the seven wonders of the ancient

world. Memories of the Seven Wonders

were not lost during the middle ages. Indeed, the Pharos stood throughout much of

the middle ages, well into the fourteenth century. However, Egypt had been cut off from

Europe by the Arab conquest in the mid-seventh century. Nevertheless, some Europeans may have seen it

during the several Crusades that attempted to take the Holy Land by landing in Egypt

first.

Some of the images used as models were drawn from remnants of Greek and Roman art, which were being surveyed with fresh eyes at this time, some were completely fanciful. Even today there is little agreement about exactly what the famous lighthouse looked like in antiquity.

Some of the images used as models were drawn from remnants of Greek and Roman art, which were being surveyed with fresh eyes at this time, some were completely fanciful. Even today there is little agreement about exactly what the famous lighthouse looked like in antiquity.

|

| Coin of Emperor Commodus Showing the Pharos Lighthouse Roman Provincial (Alexandria), 180-192 London, British Museum |

|

| Mosaic of Pharos of Alexandria from Olbia, Libya Provincial Roman, c. 4th Century Libya, Qasr Libya Museum |

|

| Ali ben Mahmud Rudbari, Pharos of Alexandria from Mudjmal al-Tavarih Iranian, 1410 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Persan 62, fol. 326 |

|

| Master of Coetivy, Flight of Cesear and Cleopatra from Faits des romains French (Paris), c. 1460-1465 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 64, fol. 401 |

|

Mosaic of St. Mark arriving in Alexandria

Italian, 1503-1515

Venice, Basilica di San Marco, Zen Chapel

|

|

Phillips Galle after Maarten van Heemskerck, The Pharos

Plate #2 of The Eight Wonders of the World

Dutch, 1572

London, British Museum

|

So, around the beginning of the fourteenth century some references to the Pharos begin to appear in the pictures of the building of the Tower of Babel. We begin to see the tower assume shapes that are neither square nor circular and we begin to see an attempt to suggest the terraced elevation of the Pharos, which harkens back to the shape of the ziggurat.

|

| Tower of Babel (Explicacio de turri babel) from Chronologia magna by Paulinus of Venice Italy (Naples), after 1329 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale MS Lain 4939, fol. 12v |

|

| Gregorio Dati, Torre Babel Italian (Florence), 1450-1499 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M721, fol.17r |

|

| Nimrod in front of the Tower of Babel (bottom left) Uomini Famosi from Chronica Figurata Italian (Rome or Naples), 1450-1550 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 9673, fol. 4 |

Other Models Appear

At the same

time that interest in the Pharos was increasing, artists were also trying to

recapture what the world of antiquity might have looked like in its own

time. From about 1500 on there was a flurry of this kind of "archaeological" fantasy painting. It attracted the attention of one of the greatest Northern painters of the age, Pieter Brueghel the Elder, and became virtually a family business for the various members of the van Valckenborgh family of Flemish painters who were active around the end of the sixteenth and beginning of the seventeenth centuries.

Most of their conjectures were fanciful, though they were drawn from reading the ancient texts that were becoming increasingly available through the growing use of the printing press. Views of the wonders of the world, such as those drawn by Maarten van Heemskerck and engraved by many other hands for well over a century, were popular and served as guides for other artists.

However, the only monuments of

the ancient world that remained fairly easily viewable to most European artists

at this time were the Colosseum and the Pantheon, both in Rome. The other great monuments still standing were

the pyramids and they were in Egypt, which was doubly distanced from European

artists by its location and the enmity of its Muslim rulers. Consequently, the images of the pyramids that

were available in Europe were largely flights of fancy (although there were two

small pyramids that were visible in Rome at the time, the pyramid of Gaius

Cestius, which still stands and another pyramid located between the Vatican and

the Castel Sant’Angelo, which was dismantled in the early 16th

century 6).

|

| Gerard Horenbout, Building the Tower of Babel from The Grimani Breviary Belgian, c. 1510-1520 Venice, Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana MS Lat. I 99, fol. 206r |

|

| Giulio Clovio, The Tower of Babel from The Farnese Hours Italian, 1546 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M69, fol.104v |

|

| Lucas van Valckenborgh, Tower of Babel Flemish, c. 1550 Paris, Musee du Louvre |

|

| Lucas van Valckenborgh, Tower of Babel Flemish, c. 1550 Private Collection |

|

| Probably from the Workshop of Guido Durantino Building of the Tower of Babel Italian (Urbino), c. 1550-1560 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

|

| Etienne Delaune, Building of the Tower of Babel French, c. 1560-1568 Philadelphia, Museum of Art |

|

| Hendrick van Cleve III, The Tower of Babel Flemish, c. 1560 Private Collection |

|

| Hendrick van Cleve, The Tower of Babel Flemish, 1560-1589 Hamburg, Hamburger Kunsthalle |

|

| Pieter Brueghel the Elder, The Tower of Babel Flemish, 1563 Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum |

|

| Pieter Brueghel the Elder, The "Little" Tower of Babel Flemish, c. 1564 Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen |

|

| Marten van Valckenborgh, The Tower of Babel Flemish, c. 1570-1600 Burnley, UK, Townley Hall Art Gallery and Museum |

|

| Anonymous, The Tower of Babel French, 17th Century Paris, Musee du Louvre |

|

| Anonymous. The Tower of Babel Flemish School, 17th Century Cambridgeshire UK, Anglesey Abbey |

|

| Jan Christianenszoon Micker. The Tower of Babel Dutch, ca. 1650 UK Government Art Collection |

|

| Tower of Babel Swiss (Zurich), 1631 London, Victoria and Albert Museum |

|

| Mattia Bortoloni, Construction of the Tower of Babel Italian, 1717-1718 Piombino Dese, Villa Cornaro |

|

| Johann Ferdinand Schor, Nimrod and the Building of the Tower of Babel Austrian, c. 1720 Prague, Villa Amerika |

Most of their conjectures were fanciful, though they were drawn from reading the ancient texts that were becoming increasingly available through the growing use of the printing press. Views of the wonders of the world, such as those drawn by Maarten van Heemskerck and engraved by many other hands for well over a century, were popular and served as guides for other artists.

|

| Phillips Galle after Maarten van Heemskerck, The Mausoleum of Hallicarnasus Plate #6 of The Eight Wonders of the World Dutch, 1572 London, British Museum |

|

| Phillips Galle after Maarten van Heemskerck, The Colosseum Plate #8 of The Eight Wonders of the World Dutch, 1572 London, British Museum |

|

| Phillips Galle after Maarten van Heemskerck, The Pyramids of Giza Plate #1 of The Eight Wonders of the World Dutch, 1572 London, British Museum |

Into the Modern World

Even though

the ancient world became more familiar to both artists and the public during

the 19th and 20th centuries, through the work of

archaeologists working in both the Egyptian and Ancient Near Eastern fields,

the image of the tower of Babel has remained somewhat fluid.

Most works of the 20th century do bear some resemblance to the ziggurat shape, if only in the emphasis on terraced levels, but the Tower still seems a construct of the mind, rather than an archaeological document.

Confusion and Dissolution versus Reconciliation and Unity

|

| James Gillray. Overthrow of the Republican Babel English, 1809 London, British Museum A political satire that uses the destruction of the Tower to represent the events of the day. |

|

| Edward Burne-Jones Design for a Window English, 1857 London, Victoria and Albert Museum |

|

| James Tissot, Building the Tower of Babel French, c. 1896-1902 New York, Jewish Museum |

Most works of the 20th century do bear some resemblance to the ziggurat shape, if only in the emphasis on terraced levels, but the Tower still seems a construct of the mind, rather than an archaeological document.

|

| M. C. Escher, The Tower of Babel Dutch, 1928 London, British Museum |

|

| Walid Siti, Tower of Babel Iraqi (Kurdish), 2001 London, British Museum |

Confusion and Dissolution versus Reconciliation and Unity

One further

thing needs to be said. The raison

d’etre of the story of the Tower of Babel is to demonstrate how the divisions

of humanity, for which the amazing variety of languages is a symptom, was the

result of mankind’s overwhelming pride in undertaking so great a worldly

project.

The three images below show how the artists of one studio responded to different commissions for the same material. They reused and adapted compositions and figures, altering the pose and size of the figures and modifying details.

Like the side by side comparisons beloved in

art history lectures, the readers were trusted to understand the relationship

from the juxtaposition.

|

| The Bedford Master, Destruction of the Tower of Babel from The Bedford Hours French (Paris), c. 1410-1430 London, British Library MS Additional 18850, fol. 17v |

|

| Master of the Echevinage, Angels Attack the Tower of Babel from Chronique de la Bouquechardiere by Jean de Courcy French, (Rouen), c. 1450-1475 London, British Library MS Harley 4376, fol. 206v |

|

| Maitre de l'Echevinage, Angels Attack the Tower of Babel from La Bouquechardiere by Jean de Courcy French (Rouen), ca. 1460 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 20124, fol. 202 |

|

| Destruction of the Tower of Babel and Descent of the Holy Spirit on the Apostles from Bible moralisee Italian (Naples), c. 1350 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 9561, fol. 14v |

|

| Descent of the Holy Spirit and Building of the Tower of Babel from Speculum humanae salvationis Italian (Bologna), c. 1350 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Arsenal 593 [ff.1-42], fol. 8 |

|

| Descent of the Holy Spirit from Rothschild Book of Hours Flemish, 1500-1505 London, British Library MS Additional 35313, fol 33v |

|

| Building the Tower of Babel from Rothschild Book of Hours Flemish (Ghent), 1500-1505 London, British Library MS Additional 35313, fol 34r |

|

| Possibly Simon Bening, Descent of the Holy Spirit from The Grimani Breviary Belgian, c. 1510-1520 Venice, Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana MS Lat. I 99, fol. 205v |

|

| Gerard Horenbout, Building the Tower of Babel from The Grimani Breviary Belgian, c. 1510-1520 Venice, Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana MS Lat. I 99, fol. 206r |

|

| Giulio Clovio, Descent of the Holy Spirit and Building of the Tower of Babel from The Farnese Hours Italian (Rome), 1546 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M69, fols.106v-107r |

©

M. Duffy, 2017

- Quentin D. Atkinson, “Phonemic Diversity Supports a Serial Founder Effect Model of Language Expansion from Africa”, Science, New Series, Vol. 332, No. 6027 (15 April 2011), American Association for the Advancement of Science, pp. 346-349. Also, W. Tecumseh Fitch, “Unity and diversity in human language”, Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences, Vol. 366, No. 1563, Evolution and human behavioural diversity, (12 February 2011), The Royal Society, pp. 376-388.

- Notes on Genesis 10 at http://www.usccb.org/bible/gn/10:10#01010008-

- Nimrod may be the Biblical name for a real person, “possibly Tukulti-Ninurta I (thirteenth century B.C.), the first Assyrian conqueror of Babylonia and a famous city-builder at home”. See note on Genesis 10:8-12 at http://www.usccb.org/bible/gn/10:10#01010008-1.

- See notes on Genesis 11 at http://www.usccb.org/bible/genesis/11

- For different interpretations of this story see Brent A. Strawn, “Holes in the Tower of Babel”, Oxford Biblical Studies Online at https://global.oup.com/obso/focus/focus_on_towerbabel/, Maria Cintorino “The Tower of Babel and the Struggle to Be Like God”, Crisis Magazine, November 7, 2016 at http://www.crisismagazine.com/2016/tower-babel-struggle-like-god and “Tower of Babel”, the Jewish Virtual Library at http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/tower-of-babel

- For the pyramids of Rome see: http://archeoroma.beniculturali.it/en/archaeological-site/pyramid-caius-cestius and http://www.atlasobscura.com/places/pyramid-of-cestius

Excerpts from the Lectionary

for Mass for Use in the Dioceses of the United States of America, second

typical edition © 2001, 1998, 1997, 1986, 1970 Confraternity of

Christian Doctrine, Inc., Washington, DC. Used with permission. All rights

reserved. No portion of this text may be reproduced by any means without

permission in writing from the copyright owner.