.jpg) |

Jesus Appears in Galilee from the Drogo Sacramentary French (Metz), 9th Century Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 9428, fol. 64v |

After this, Jesus revealed himself again to his disciples at the Sea of Tiberias.

He revealed himself in this way.

Together were Simon Peter, Thomas called Didymus, Nathanael from Cana in Galilee, Zebedee's sons, and two others of his disciples.

Simon Peter said to them, "I am going fishing." They said to him, "We also will come with you."

So they went out and got into the boat, but that night they caught nothing.

When it was already dawn, Jesus was standing on the shore; but the disciples did not realize that it was Jesus.

Jesus said to them, "Children, have you caught anything to eat?" They answered him, "No."

So he said to them, "Cast the net over the right side of the boat and you will find something." So they cast it, and were not able to pull it in because of the number of fish.

So the disciple whom Jesus loved said to Peter, "It is the Lord."

When Simon Peter heard that it was the Lord, he tucked in his garment, for he was lightly clad, and jumped into the sea.

The other disciples came in the boat, for they were not far from shore, only about a hundred yards, dragging the net with the fish.

When they climbed out on shore, they saw a charcoal fire with fish on it and bread.

Jesus said to them, "Bring some of the fish you just caught."

So Simon Peter went over and dragged the net ashore full of one hundred fifty-three large fish. Even though there were so many, the net was not torn.

Jesus said to them, "Come, have breakfast." And none of the disciples dared to ask him, "Who are you?" because they realized it was the Lord.

Jesus came over and took the bread and gave it to them, and in like manner the fish.

This was now the third time Jesus was revealed to his disciples after being raised from the dead.

John 21:1-14

Of all the apparitions of Jesus in the time between the Resurrection and the Ascension, this is both one of the most mysterious and one of the most real. It takes place in a familiar location, the Sea of Galilee, where so much of Jesus’ ministry had taken place, the area that was home for most of the disciples.

The scene opens with the disciples, returned from Jerusalem, following Peter’s lead “I am going fishing”. After an unproductive night, as they return to harbor, they see a figure on the shore, probably indistinct in the early morning light. He instructs them to cast their nets again and they make a huge catch. In the catch they recognize a situation they have experienced once before (Luke 5:4-11) and they realize that the figure on the shore is the same person that had been with them then. When they arrive on shore they find that He has prepared breakfast for them and He feeds them.

The setting on the shore of the great lake, the misty morning light, the catch, the recognition of the Risen One, the sharing of bread and fish, recalling both the miraculous feeding of the multitudes and the Last Supper combine to create the mysterious reality of this apparition. Ghosts may appear, but they don’t cook and share meals with their friends.

It is surprising, then, that these verses have not inspired more works of art. One of the aspects of this passage, which may have caused difficulties for artists and their advisors is how to distinguish this scene from other, very similar, scenes, i.e., the miraculous draught of fish associated with the calling of the apostles or the scene in which Peter leaves the boat and attempts to walk on water. The differences between these scenes and that of the post-Resurrection encounter described by John are sometimes subtle.

Among the elements that hint at the post-Resurrection scene are: Jesus stands on the shore, not on the water, the sea is calm and not stormy (although this is not always so), Peter jumps into the water when the boat is near the shore, there are often elements of the meal Jesus invites the apostles to somewhere in the picture.

|

Michiel van der Borch, Miraculous Draught of Fish

From Rhimebible by Jacob van Maerlant

Dutch (Utrecht), 1332

The Hague, Meermano Museum

MS RMMW 10 B 21, fol. 151r |

|

Lluis Borrassa, Peter Reaches Christ on the Shore

Spanish (Catalan), 1411-13

Terrasa (Catalonia), Church of Sant Pere |

|

The Risen Jesus Appears on the Sea of Galilee

From Chronicle of the Kings of England from William the Conqueror to Henry IV

English, c. 1430-1440

The Hague, Koninklijk Bibliotheek

MS KB 75 A 2-4, fol. 62v

|

The images above are still somewhat ambiguous, although they do show Jesus to be standing on the shore, as Peter walks through the shallow water and are, therefore, most probably illustrations of John 21. However, the image immediately above is definitely an illustration of the passage. Not only is the Risen Jesus standing on the shore as Peter comes through the water, but in the right background one can see Jesus and the Apostles gathered around a fire cooking.

|

Konrad Witz, Apparition of Christ in Galilee

Swiss, 1443

Geneva, Musée d'Art et d'Histoire

|

In the painting by Konrad Witz, originally in Geneva’s St. Peter’s Cathedral and now in the Geneva

Museé d’Art et d’Histoire, we see the moment when Peter swims to shore, as the other disciples maneuver the boat and the catch behind him. In the background, we see the neat landscape imagined by Witz for the shores of Galilee, probably based on medieval Geneva itself. Originally in the cathedral, it was removed when Geneva officially adopted Calvinism in 1535.

|

Master of the Harley Froissart, Christ Appearing to the Apostles on the Sea of Galilee

from Bible historiale by Guiard des Moulins

Flemish, 1470-1479

London, British Library

MS Royal 15 D I, fol. 368 |

|

Attributed to Colijn de Coter, Christ Appearing to the Apostles on the Sea of Galilee

Flemish, c. 1500

Autun, Musée Rolin |

In the sixteenth century many artists created works that more effectively distinguish this scene from the other, earlier events.

|

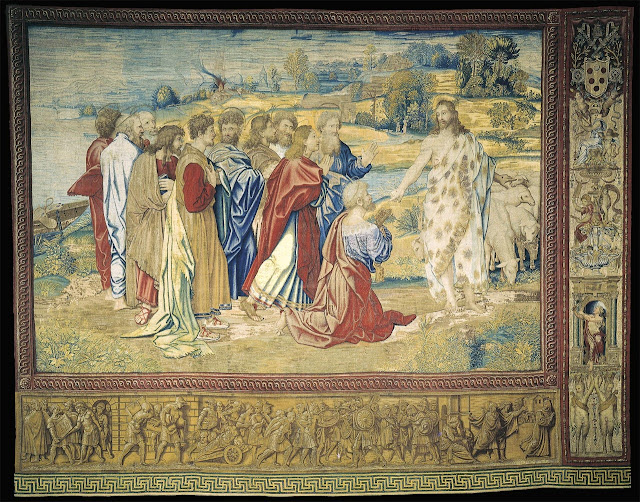

Anonymous, The Risen Christ Appearing to the Apostles on the Sea of Galilee

French or Flemish, 16th Century

Abbeville, Musée Boucher de Perthes |

The anonymous French or Flemish artist who painted this picture handled the subtleties of the scene by including several successive scenes in one composition. In the middle distance we see the Apostles out on the sea fishing. At the left front they have arrived in port and are greeted by Jesus. At the right Peter kneels to adore the Risen Jesus and in front of them is a grill with two fish cooking.

|

Herri met de Bles, Final Apparition of Christ to His Disciples

Flemish, c. 1530-1550

Buenos Aires, Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes |

In this image by Herri met de Bles the Risen Jesus welcomes Peter to shore as the other Apostles struggle to bring the boat into port. The figure of Jesus is definitely attired as the Risen Jesus. He is nude to the waist and the wound on His side and right hand are obvious. He also carries the Resurrection banner, by then a conventional part of Resurrection iconography. In the background, just above the head of St. Peter we can see the group, gathered around a fire, at the entrance of a cave.

|

Joachim Beuckelaer, The Risen Christ Appears to the Apostles on the Sea of Galilee

Dutch, 1563

Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum |

Joachim Beuckelaer made a career out of painting still lives and market and kitchen scenes, some of which have a Biblical scene positioned in the background. He uses a similar arrangement here, showing us the busy trade of the fishing port in the foreground with boats being unloaded, fish sold, bargaining going on. Meanwhile, in the background, Peter walks through the sea to meet Jesus, who waits onshore. And, farther in the background, Jesus and the Apostles sit at a table while two fish are cooking on an open fire.

|

Maerten van Heemskerck, The Risen Christ Appears to the Apostles on the Sea of Galilee

Flemish, 1567

Barnard Castle (County Durham, UK), The Bowes Museum |

Maerten van Heemskerck puts his knowledge of ancient buildings to use in this broad view of the event. From what appears to be a high view of the region we can see not just the lake but the buildings and ruins that grace its shores. And, from a distance, we can see Jesus waiting as Peter walks through the sea and the other Apostles continue working on the boat. There is no fire here, but next to Jesus is the symbol of the fish, similar to those used by the early Christians as a covert sign of the faith. Early Christian sites were being excavated for the first time in centuries at Rome during the sixteenth century and it is probable that Heemskerck could have become acquainted with them during the time he spent there.

|

Jacopo Tintoretto, Christ at the Sea of Galilee

Italian, c. 1575-1580

Washington, National Gallery of Art |

At first, this beautiful painting by Tintoretto might seem to be somewhat ambiguous regarding just which incident is being depicted. However, although no evidence of a meal in preparation is visible, the proximity of Peter to the shore and the fact that Jesus is standing on the shore and not on the water suggest that this if depicting the event in the Gospel of John.

|

Grabenberger Brothers (Michael Christoph, Johann Bernhard and Michael Georg), Christ Appearing at the Sea of Galilee

German, 1682-1683

Garsten (AU), Parish Church of the Assumption |

This image, part of the decoration of the former Garsten Abbey church, includes all the elements of the story from John 21. Jesus stands on the shore, summoning the Apostles. Behind Him are fish and bread, ready for breakfast. Peter strides through the water, while behind him the other Apostles struggle to bring in their full nets.

|

Sebastiano Ricci, Christ Appearing to the Apostles at the Sea of Galilee

Italian, c. 1695-1697

Detroit, Institute of Arts |

There is no evidence for a meal in preparation in this painting by Sebastiano Ricci, but various other elements suggest that it illustrates John 21. Jesus stands on the seashore with a radiance surrounding His head that suggests that this is a post-Resurrection event. Also, the boat is not far from shore. Some on board struggle to bring in the catch, while others point excitedly to Jesus and Peter slogs through the shallow water.

In the late 1880s the French painter, James Tissot, began a huge number of watercolor paintings of the New Testament that are now in the Brooklyn Museum

1. Among them are several that illustrate the passage from John 21.

|

James Tissot, Jesus Appears on the Shore of the Sea of Galilee

French, 1886-1894

New York, Brooklyn Museum |

The first is very similar in composition to the painting by Witz and Tintoretto. Jesus, seen from behind, stands on the seashore, calling to the disciples who are on the lake. Behind him is a fire, planted amid stones. Again we see the shores of the lake. But, where Witz used his own imagination and the landscape of Switzerland to create his setting, Tissot had actually spent time in the Holy Land and gives us a vision of what the scene might really have looked like.

|

James Tissot, St. Peter Alerted by St. John to the Presence of the Lord Casts Himself into the Water

French, 1888-1894

New York, Brooklyn Museum |

|

James Tissot, Meal of Our Lord and the Apostles

French, 1886-1894

New York, Brooklyn Museum |

Tissot’s series also includes an illustration of the scenes that follow, Peter's jump into the water and the breakfast on the beach. The latter makes explicit the scenes that earlier painters had sent to the background. Set in the same cove as the first illustration the disciples sit in a semi-circle in front of Jesus, their backs to the sea and their beached boats. Jesus tends the fire and a roasting fish Himself. But, in keeping with the mystery of His Resurrection, we do not see His face in either picture.

© M. Duffy, 2011, amended 2017

- He also prepared another series of paintings between 1896-1902 of the Old Testament. These are also in New York, at the Jewish Museum. These two cycles probably make James Tissot the artist who has most thoroughly illustrated the Bible. Most interesting is that Tissot spent considerable time in the Holy Land during the years in which he was working on these series. At this time the area was still largely untouched by the changes of the modern world. However, considerable archaeological activity had taken place to unearth at least some of the material culture of Biblical times. For these reasons they are probably as close as can be imagined to illustrating the world of the Bible as it was.

.jpg)