|

Christ at Emmaus

From a Picture Bible

French, 1190-1200

The Hague, Koninklijk Bibliotheek

MS KB 76 F 5, fol. 22v

|

he took bread, said the blessing, broke it, and gave it to them.

With that their eyes were opened and they recognized him,

but he vanished from their sight.

Then they said to each other, “Were not our hearts burning within us

while he spoke to us on the way and opened the Scriptures to us?”

So they set out at once and returned to Jerusalem

where they found gathered together the Eleven and those with them who were saying,

“The Lord has truly been raised and has appeared to Simon!”

Then the two recounted what had taken place on the way

and how he was made known to them in the breaking of the bread.”

(Luke 24:30-35) Gospel for Third Sunday of Easter, May 8, 2011

As discussed in my previous post, images from the journey to Emmaus are somewhat scarce, but images of the moment of recognition at the dining table (what came to be called “The Supper at Emmaus”), are numerous and often the work of great painters.

Prior to 1600 there were already images of this scene. Among them are an early 12th century French pictorial Bible from the Benedictine abbey of St. Bertin, now in the Koninklijk Bibliotheek at the Hague, seen above. Most of them are combined with images of the journey to Emmaus, either within the same image or as a part of a group of images related to the Resurrection, as, in fact, is this one.

|

Scenes from the Resurrection narratives

from a Picture Bible

French, 1190-1200

The Hague, Koninklijk Bibliotheek

MS KB 76 F 5, fol. 22v

|

At its simplest, the scene of the recognition shows Jesus and the two disciples seated at a table. Jesus is always shown holding, or actually in the act of breaking, a piece of bread. The disciples are shown reacting in some manner.

|

| The Disciples Recognize Jesus from Miniatures of the Life of Christ France (Northeast), 1170-1180 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M 44, fol. 13r |

|

| Ivory Panel From a Box The Disciples Recognize Jesus French, 15th Century Paris, Musée de Cluny, Musée national du Moyen Age |

|

| Master of Catherine of Cleves, The Disciples Recognize Jesus from the Hours of Catherine of Cleves Dutch (Utrecht), c. 1435-1445 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M 945, fol. 139r |

|

| Jean Poyer, The Disciples Recognize Jesus from the Prayer Book of Anne de Bretagne French (Tours), 1492-1495 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M 50, fol. 8r |

From about the year 1500 more figures began to appear. Serving men and women are added, as are cats and dogs and children. Also added are figures contemporary with the painting itself who become visionary witnesses to the scene and, therefore, invite us into the scene as witnesses as well.

|

| Marco Marziale, The Disciples Recognize Jesus Italian, 1506 Venice, Gallerie dell'Accademia |

|

| Albrecht Durer, The Disciples Recognize Jesus Woodcut, from The Small Passion German, c. 1510 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

|

| The Disciples Recognize Jesus Dutch, c. 1520 Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum |

The painting by Jacopo Pontormo, dated 1525, and possibly based on Durer's composition, begins to take us in a new direction. The seated figures are shown sitting around the table, not all together on one side that faces us. Therefore, the two disciples are shown with their backs to us and are not yet reacting, because Jesus has not yet broken the bread.

|

| Jacopo Pontormo, The Supper at Emmaus Italian, 1525 Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi |

In addition to the two disciples and wait staff Pontormo has added two pious witnesses, who show their astonishment, even before the disciples. Since the painting was commissioned for the Carthusian monastery of Galluzo the witnesses are, no doubt, Carthusian monks. Typically for a Mannerist painter, the figures, especially the Biblical figures, are shown in slightly contorted poses.

More importantly, Christ is shown not actually breaking the bread but apparently blessing it. This gesture would be the one that future works would use most often.

Pontormo has also added a pair of cats and a small dog at the bottom of the picture. One cat peers out from under the chair of the disciple in green, while the puppy and the other cat appear at the extreme left of the bottom of the picture. All the animals look outwards from the picture, at us, and thus draw us into the picture as witnesses also. (The eye in a triangle, a symbol for the presence of God may not be original to the picture, but may have been added later.)

During the sixteenth century and into the first half of the seventeenth century, the blessing gesture almost completely replaced the breaking of the bread as the action of the Risen Jesus. Very often the disciples are shown as still not recognizing Him, in keeping with the Gospel for "he was made known to them in the breaking of the bread" (Luke 24:35), and, therefore, by implication, not until then.

|

| Titian, Supper at Emmaus Italian, c. 1530s Paris, Musée du Louvre |

|

| Jacopo Bassano, Supper at Emmaus Italian, c. 1538 Cittadella, Parish Church, Sacristy |

|

| Tintoretto, Supper at Emmaus Italian, 1542-1543 Budapest, Szépmûvészeti Múzeum |

One hundred years later, at the beginning of the seventeenth century, Michelanglo Merisi da Caravaggio, known simply as Caravaggio, refocused attention on the central action of the Supper at Emmaus, the interaction between Jesus and the disciples.

|

Caravaggio, Christ at Emmaus

Italian, 1601

London, National Gallery

|

Moreover, the gestures of Christ and the reaction of the disciples suggest that the reference to “the breaking of the bread” as more than a reference to a Biblical quotation or to a simple act. They suggest, in fact, a reference to the Eucharist. In pictorial terms they are saying that the Eucharist is the place where we recognize the Risen Lord. Indeed, Caravaggio made this quite explicit in his painting. By juxtaposing the bread of the disciples with the basket of fruit and its very prominent bunch of grapes, Caravaggio is highlighting two traditional symbols for the Eucharist -- bread and grapes. The dramatic blessing gesture of Christ also suggests the moment of Consecration in the Mass.

And gradually also, the dramatic lighting was first used, and then manipulated, to create a distinction around the figure of Jesus which is not found in the Caravaggio painting. Over time the figure of Jesus came to be "illumined" with supernatural light. As with the other variations on this subject, the artists who worked on these pictures ranged from the merely competent to the great masters.

|

| Antonio Giarola, Supper at Emmaus Italian, 1620-1630 Rennes, Musée des Beaux-Arts |

|

| Diego Velazquez, The Supper at Emmaus Spanish, c. 1620 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

|

| Jacopo da Empoli, Supper at Emmaus Italian, c. 1620 St. Petersburg, State Hermitage Museum |

|

| Hendrick Terbrugghen, Supper at Emmaus Dutch, c. 1621 Berlin, Schloss Sanssouci |

|

| Attributed to Trophime Bigot, Supper at Emmaus French, c. 1620-1630 Chantilly,Musée Condé |

|

| Rembrandt van Rijn, Supper at Emmaus Dutch, c. 1629 Paris, Musée Jacquemart-Andre |

|

| Dirck Santvoort, Supper at Emmaus Dutch, 1633 Paris, Musée du Louvre |

Rembrandt's painting of about 1629, with its night effects lighting that silhouetted the figure of Jesus against the light, creating an aura of light around Him, was picked up by later artists to silhouette Him as well. However, in the later paintings He is the source of the light as well as the figure revealed by it.

|

| Jean Restout. Supper at Emmaus French, 1735 Lille, Palais des Beaux-Arts |

|

| Charles Antoine Coypel French, c. 1730-1740 Paris, Musée Carnavalet |

|

| Joseph Winterhalder the Younger, Supper at Emmaus Czech, c. 1772-1773 Vienna, Belvedere Museum |

|

| Philip James de Loutherbourg, Supper at Emmaus French, 1797 Birmingham (UK), Birmingham Museums Trust |

Not every artist joined in the explosion of light effects. Some remained solidly rooted in telling the story. Many, though not all, of these artists were French or Flemish.

|

| Philippe de Champaigne, Supper at Emmaus Franco-Flemish, c. 1650 Ghent, Museum voor Schone Kunsten, |

Other French artists (and Champaigne himself) continued to work with this vision of the subject.

|

| Peter Paul Rubens, Supper at Emmaus Flemish, 1638 Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado |

|

| The LeNain Brothers, Supper at Emmaus French, 1645 Paris, Musée du Louvre |

|

| Jacob Jordaens, Supper at Emmaus Flemish, c. 1645-1665 Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland |

|

| Laurent de La Hyre. Supper at Emmaus French, 1656 Grenoble, Musée de Grenoble |

|

| Philippe de Champaigne, Supper at Emmaus French, 1656 Angers, Musée des Beaux-Arts |

|

| Attributed to Jean Jouvenet, Supper at Emmaus French, c. 1690-1700 Nantes, Musée des Beaux-Arts |

|

| Pierre Joseph Verhaghen, Supper at Emmaus Flemish, 1772 Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum |

|

| Willem Herreyns, Supper at Emmaus Belgian, 1808 Antwerp, Cathedral of Our Lady |

|

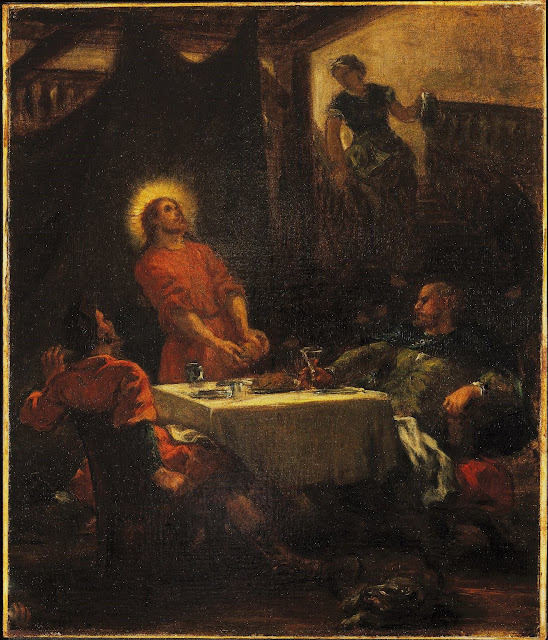

| Eugene Delacroix, Supper at Emmaus French, 1853 New York, Brooklyn Museum |

|

| Carl Heinrich Bloch, Supper at Emmaus Danish, 1870s Provo (UT), Brigham Young University Museum of Art |

|

| Henry Ossawa Tanner, Supper at Emmaus American, 1905 Paris, Musée d'Orsay |

First there were some attempts to set the scene in the current day and in current situations. So, instead of a scene set in an inn we find scenes of the Risen Jesus breaking bread in bourgeois dining rooms and in a working class cafe.

|

| Jacques Emile Blanche, Supper at Emmaus French, 1891-1892 Rouen, Musée des Beaux-Arts |

|

| Leon-Augustin L'Hermitte, Friend of the Humble-Supper at Emmaus French, 1892 Boston, Museum of Fine Arts |

|

| Pascal-Adolphe Jean Dagnan Bouveret, Supper at Emmaus French, 1896-1897 Pittsburgh, Carnegie Museum of Art |

After 1900 any resemblance to the work of the past was purely at the will of the artist. Most chose to do something else while keeping the title.

© M. Duffy 2011, amended 2017