|

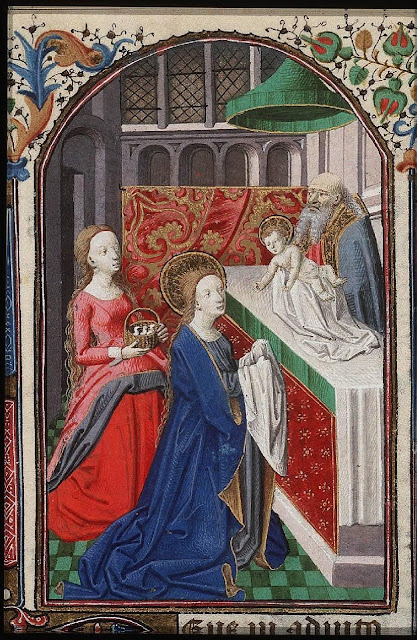

| Alvaro Pirez, The Presentation Portuguese, c. 1430 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

"When the days were completed for their purification

according to the law of Moses,

Mary and Joseph took Jesus up to Jerusalem

to present him to the Lord,

just as it is written in the law of the Lord,

Every male that opens the womb shall be consecrated to the Lord,

and to offer the sacrifice of

a pair of turtledoves or two young pigeons,

in accordance with the dictate in the law of the Lord.

Now there was a man in Jerusalem whose name was Simeon.

This man was righteous and devout,

awaiting the consolation of Israel,

and the Holy Spirit was upon him.

It had been revealed to him by the Holy Spirit

that he should not see death

before he had seen the Christ of the Lord.

He came in the Spirit into the temple;

and when the parents brought in the child Jesus

to perform the custom of the law in regard to him,

he took him into his arms and blessed God, saying:

“Now, Master, you may let your servant go

in peace, according to your word,

for my eyes have seen your salvation,

which you prepared in the sight of all the peoples:

a light for revelation to the Gentiles,

and glory for your people Israel.”

The child’s father and mother were amazed at what was said about him;

and Simeon blessed them and said to Mary his mother,

“Behold, this child is destined

for the fall and rise of many in Israel,

and to be a sign that will be contradicted

—and you yourself a sword will pierce—

so that the thoughts of many hearts may be revealed.”

There was also a prophetess, Anna,

the daughter of Phanuel, of the tribe of Asher.

She was advanced in years,

having lived seven years with her husband after her marriage,

and then as a widow until she was eighty-four.

She never left the temple,

but worshiped night and day with fasting and prayer.

And coming forward at that very time,

she gave thanks to God and spoke about the child

to all who were awaiting the redemption of Jerusalem.

When they had fulfilled all the prescriptions

of the law of the Lord,

they returned to Galilee, to their own town of Nazareth.

The child grew and became strong, filled with wisdom;

and the favor of God was upon him. Luke 2:22-40

(Gospel for the Feast of the Presentation of the Lord,

February 2)

St. Luke, who gives us the most detailed account of the

birth of Jesus, from the Annunciation to this event of the Presentation, is

traditionally believed to have been in touch with Mary and to have gained his

knowledge of these events from her or at least from someone who knew her

well. The intimate details of events such

as those recounted in the Gospel for the Presentation would seem to confirm

this. However, he also wants to show his

readers that the parents of Jesus were devout and humble Jews, careful to

fulfill the requirements of the Law, even as they raised the One who would

bring salvation to Israel and to all people.

,%20c.%20975-1000_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Latin%209448,%20fol.%2028r+3.jpeg) |

| The Presentation From a Troparium, Prosarium, Graduale German (Prüm), c. 975-1000 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 9448, fol. 28 |

The Mosaic law laid down two requirements on the birth of a first son to any couple. First, the male child was to be consecrated to the Lord as a reminder of the last plague of the Exodus, during which the first born of the Egyptians were killed (Exodus 13). But the child could be redeemed for a payment of five silver sheckels to a member of a priestly clan (Numbers 18:16).

|

| Fra Angelico, The Presentation Italian, c. 1433-1434 Cortona, Museo Diocesano |

Second, a woman who had given birth to a boy

was required to spend 40 days without touching anything sacred. At the end of this time “she shall bring to the priest at the entrance of the tent of meeting a

yearling lamb for a burnt offering and a pigeon or a turtledove for a

purification offering…If, however, she cannot afford a lamb, she

may take two turtledoves or two pigeons, the one for a burnt offering and

the other for a purification offering. The priest shall make atonement for her,

and thus she will again be clean.” (Leviticus 12:1-8)

,%20c.%201445-1450_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Latin%209473,%20fol.%2055r_2.jpeg) |

| The Purification From the Hours of Louis of Savoy French (Savoy), 1445-1460 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 9473, fol. 55r |

Luke conflates what would be two separate events, the redemption of the child and the purification of the mother, into one story. Mary and Joseph bring their son to the Temple to pay his ransom and to certify Mary as recovered from childbirth. He then weaves into the tale the reactions of Simeon and Anna, two pious old people who have prophetic gifts and who recognize the child for Who He is.

|

| Ambrogio da Fossano, known as Il Bergognone, The Presentation Italian, c. 1497-1500 Lodi, Tempio Civico della Beata Vergina Incoronata |

This is another epiphany. There have been epiphanies to the lowly shepherds of Bethlehem, to the learned Wise Men from the Gentile nations and now there is an epiphany to those in Jerusalem who are capable of seeing.

|

| Giuseppe Cesari, The Purification Italian, c. 1617-1627 Rome, Church of Santa Maria in Vallicella |

We know that a feast of the Presentation/Purification was celebrated in Jerusalem as early as the fourth century when it was described by the pilgrim, Egeria. From there it gradually spread to the entire church, reaching the church in Rome by the seventh century. In the West it became known as the Purification of Mary and was set on February 2nd.

|

| Rembrandt, The Presentation Dutch, 1631 The Hague, Mauritshuis Museum |

By the eleventh century a solemn blessing of and procession with candles had been introduced and the day began to be known as Candlemas. 1 The procession with candles marked the entry of “the light for revelation to the Gentiles and glory of your people Israel” into the Temple. Over time it began to be seen as the last event of the Christmas season. It was the day on which people turned their attention from the coming of Christ, removing any remaining decorations, and began their preparation for Easter with the onset of Lent.

Artists have given us many, many images of the event and

these images tell us some very important things.

The Meeting with Simeon

The lovely words of Simeon have been preserved in the daily

prayer of the Church, the Divine Office (or the Hours) as the Biblical canticle

for the daily prayer that ends the day, Compline. Called the “Nunc dimittis” it is recited

every evening before bed by all who pray the Hours, be they priest, religious or

lay person. So the images that form in

the mind have been given visual form by artists.

The simplest image is that of the meeting between the aged Simeon and the Child Jesus. Many artists have chosen this as the image they want to present. These images frequently represent the event as taking place outside the temple building, as is implied by the text of the Gospel. Details such as the two pigeons for the offering may be included.

|

| Philippe de Champaigne, The Presentation French, 1648 Brussels, Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts |

|

| Johann Hiebel, The Presentation German, c. 1727-1731 Litomerice (Czech Republic), Jesuit Church of the Annunciation |

The images above are part of this iconographic stream.

The First Hint of Public Sacrifice

But there is another set of images, far surpassing the

Meeting in number, that have been the favored image type, especially during the

Middle Ages and early Renaissance.

These images call to mind, not the entrance of the light into the temple, but the impending sacrifice on the Cross. This, the dark side of the Christmas story, is often ignored today, but was definitely fully realized in earlier centuries. Christ came as a child to suffer and to die for humanity. He is the sacrificial victim, the pure Lamb of God, whose coming was foreshadowed in earlier images of sacrifice, even including the offerings of his own parents.

In these images the visual emphasis is not on the meeting between the old man and the Child, but the future of the Child as a willing sacrificial victim. In these images the Christ Child is shown in relation to the altar of the temple. He may be placed or about to be placed on it, and shown sitting, standing or lying on it, or it may simply be in the space between Mary and Simeon (or sometimes a temple priest). 2 In addition, some of the other figures in the story, such as St. Joseph and the prophetess, Anna, may not be there at all.

|

| The Presentation From the Sacramentary of Drogo French (Metz), c.850 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 9428, fol.38r |

These images call to mind, not the entrance of the light into the temple, but the impending sacrifice on the Cross. This, the dark side of the Christmas story, is often ignored today, but was definitely fully realized in earlier centuries. Christ came as a child to suffer and to die for humanity. He is the sacrificial victim, the pure Lamb of God, whose coming was foreshadowed in earlier images of sacrifice, even including the offerings of his own parents.

|

| The Presentation From a Sacramentary German (Reichenau), c. 1020-1040 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 18005, fol. 42v |

Consequently, in these images

he takes the place, sometimes directly, but always at least visually, on the

altar where the temple sacrifices also lay.

|

| The Presentation and the Crucifixion, Ivory Diptych French, 14th Century New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

On the other hand, this altar itself often looks forward to the Christian

sacrifice of the Mass. The altars are

frequently draped in cloth, just as the altar is draped for the celebration of

the Mass.

|

| The Presentation From an Evangeliary German (Prüm), c. 1100-1130 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 17325, fol. 21v |

|

| The Presentation From the St. Alban's Psalter English (St. Albans), c. 1121-1146 Hildesheim, Dombibliothek fol.28 |

|

| The Presentation From the Psalter of St. Louis and of Blanche de Castille French, c. 1225 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Arsenal 1186, fol.18 |

|

| Guido da Siena, The Presentation Italian, 1270s Paris, Musée du Louvre |

|

| The Presentation From a Psalter French (St.Omer), c. 1275-1300 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Smith-Lesouef 20, f.12v |

|

| Master of Banacavallo, The Presentation Italian (Imola), c.1278 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

|

| Pietro Cavallini, The Presentation Italian, c. 1285-1295 Rome, Church of Santa Maria in Trastevere |

|

| Giotto, The Presentation Italian, c. 1304-1306 Padua, Scrovegni/Arena Chapel |

|

| Duccio, The Presentation From the Maestà Altarpiece Italian, c. 1308-1311 Siena, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo |

|

| The Presentation From The Cloisters Apocalypse French (Normandy), c. 1330 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Cloisters Collection Accession Number 68.174, fol.2r |

|

| The Presentation From a Bible moralisee Italy (Naples), c. 1350 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 9561, fol . 137v |

|

| Melchior Broederlam, The Presentation Flemish, c. 1393-1399 Dijon, Musée des Beaux-Arts |

|

| Master of the Prado Adoration of the Magi, The Presentation Flemish, c. 1470-1480 Washington, National Gallery of Art |

|

| Rambures Master, The Presentation and its Old Testament Precedents From a Biblia pauperum French (Hesdin or Amiens), c. 1470 The Hague, Museum Meermano-Westreenianum MS 10 A 15, fol. 22v |

|

| Follower of Master of Jean Rolin, The Presentation From a Book of Hours French, (Paris), c. 1450 The Hague, Koninklijk Bibliothek MS 74 F 1, fol. 80r |

|

| Follower of Jean Pichore, The Presentation From a Book of Hours French (Paris), c. 1500 The Hague, Koninklijk Bibliothek MS 74 G 22, fol. 95v |

This may have had even greater force than it may at first appear to us, because in the Middle Ages there were frequently reported visions of the apparition of a small child in the hands of the priest following the consecration of the Mass, when the bread and wine become the Body and Blood of Christ. These apparitions were so well known that St. Thomas Aquinas even devotes to them a portion of the discussion on the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist in the Summa Theologica.4

|

| Raphael, The Presentation Italian, c. 1502-1503 Vatican City, Pinacoteca Vaticana |

|

| Jan Joest of Kalkar, The Presentation Dutch, 1508 Kalkar Kreis Kleve, Catholic parish church of St. Nicholas |

|

| Jan van Scorel, The Presentation Dutch, c. 1524-26 Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum |

|

| Anonymous, The Presentation Dutch, c. 1601-1650 Altenburg, Lindenau Museum |

There are also a few images that don’t fit either type very well. While not including the actual altar of sacrifice, they often show some of the other elements that signal the reference to sacrifice, even if it is just a reluctance on the part of the participants to hand Him back and forth.

|

| Andrea Mantegna, The Presentation Italian, c. 1460 Berlin, Gemäldegalerie der Staatliche Museen zu Berlin |

|

| Vittore Carpaccio, The Presentation Italian, 1510 Venice, Gallerie dell'Accademia |

|

| Jean Bourdichon, The Presentation From Grandes Heures d'Anne de Bretagne French (Tours), c. 1503-1508 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 9474, fol. 70v |

|

| Andrea Celesti, The Presentation Italian, c.1710 Venice, Church of San Zaccaria |

Giovanni DomenicoTiepolo, The Presentation

Italian, 1754

Stockholm, National Museum

|

Consequently, we can see that not only is the feast of the Presentation of Jesus/Purification of Mary/Candlemas about the event of Jesus’ first experience of the temple or of his meeting with Simeon or of the prophecies of Simeon and Anna, but it is about his impending sacrifice and about the prolongation of that sacrifice that we know as the Eucharist.

© M. Duffy, 2016

________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________

1.

For information on the feast of the

Presentation/Purification see: Holweck,

Frederick. "Candlemas." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol.

3. New York: Robert Appleton Company,1908. 2 Feb. 2016 .

2.

Schorr, Dorothy C., “The Iconographic

Development of the Presentation in the Temple”, The Art Bulletin, Vol.

28, No. 1, March 1946, pp. 17-32.

3.

Sinanoglou, Leah. “The Christ Child as

Sacrifice: A Medieval Tradition and the

Corpus Christi Plays”, Speculum, Vol. 48, No. 3, July 1973, pp. 491-509.

4.

Aquinas, St. Thomas. The Summa Theologica of St. Thomas Aquinas,

Second and Revised Edition, 1920. Literally

translated by Fathers of the English Dominican Province, Online Edition

Copyright © 2008 by Kevin Knight, Part III, Question 76, Article 8.

Scripture texts in this

work are taken from the New American Bible, revised edition© 2010,

1991, 1986, 1970 Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, Washington, D.C. and are

used by permission of the copyright owner. All Rights Reserved. No part of the

New American Bible may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing

from the copyright owner.

No comments:

Post a Comment