|

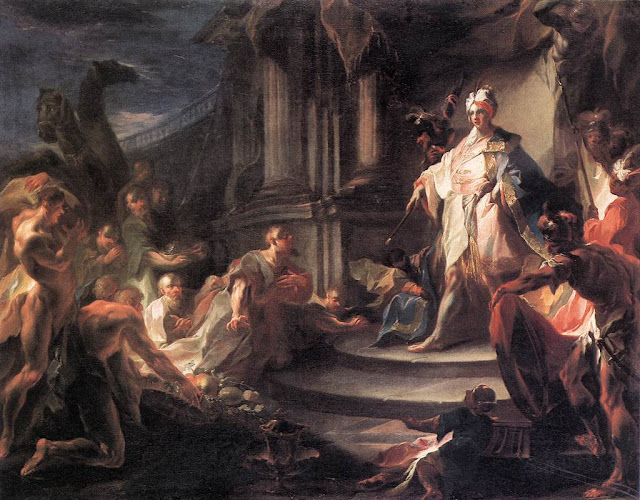

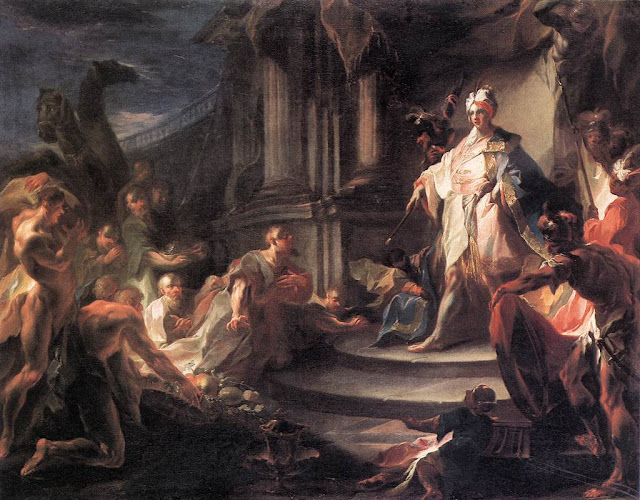

+Attributed to Andrea Schavone, Joseph Judging His Brothers

Italian, 16th Century

Chambery, Musee des Beaux-Arts |

This year the daily Mass readings for July 9th and 10th tell the Old Testament story of Joseph, he who was sold into slavery by his brothers, became a high ranking Egyptian official and eventually became reconciled to his family when they came to beg for food during a famine in Palestine. The climactic moment comes in the passages which form the reading for Thursday when, after testing them in previous passages, Joseph reveals his identity and tells his brothers

"I am your brother Joseph, whom you once sold into Egypt.

But now do not be distressed, and do not reproach yourselves for having sold me here. It was really for the sake of saving lives that God sent me here ahead of you.

For two years now the famine has been in the land, and for five more years tillage will yield no harvest.

God, therefore, sent me on ahead of you to ensure for you a remnant on earth and to save your lives in an extraordinary deliverance.

So it was not really you but God who had me come here; and he has made of me a father to Pharaoh, lord of all his household, and ruler over the whole land of Egypt.” (Genesis 45:5-8)

The story of Joseph is, of course, a familiar one. But, rather surprisingly, there are not as many depictions of the climactic scene in art as there are for the earlier episodes of his betrayal by his brothers, who sold him into slavery, and his rise in Egyptian society. Many focus on the incident in which he had to repulse the romantic advances of the wife of the Egyptian official Potiphar (Genesis 39). This is probably no surprise because tales of spicy advances have always been highly favored, and the reversal of usual roles in the story of Joseph and Potiphar’s wife makes for a nice variation on the usual formula.

While looking for images to illustrate the readings about Joseph and his reunion with his repentant family I couldn’t help but notice that, in addition to demonstrating, by their small numbers, that “sex sells” over family reconciliation, the images of Joseph and his brothers also illustrate an interesting development in western European art.

Images of Joseph as the high Egyptian official and in his meeting with his brothers seem to cluster in the later history of European art. And, within that cluster there is a difference between images made before 1800 and those made after 1800.

Images Before 1800

The earlier images tell a reasonably straightforward story, based on the biblical account. They make little effort to set the incident in any particular time period or place. The images are so lacking in special decorative motifs that they could even conceivably be read as records of recent history.

|

+Joseph Recognized By His Brothers

From the Psalter of St. Louis

Franch (Paris), c. 1270

Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France

MS Latin 10525, fol. 25v |

|

* Joseph Forgiving His Brothers

From a Bible historiee

English, c. Late 13th-Mid 14th Century

Manchester, The John Rylands Library

MS French 5, fol. 39v |

,%20Last%20Quarter%20of%20the%2013th%20Century_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Francais%2020125,%20fol.%2070r.jpg) |

* Joseph Revealing Himself to His Brothers

From an Ancient History

Latin Kingdom (Acre), Last Quarter of the 13th Century

Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France

MS Francais 20125, fol. 70r |

|

+ Master of the Roman de Fauvel, Joseph Revealing Himself to His Brothers

From a Bible historiale byr Guiard des Moulins

French (Paris), c.1325-1350

Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France

MS Francais 156, fol. 40r |

,%20c.%201333-1334_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Francais%20316,%20fol.%2075v.jpeg) |

* Master of the Roman de Fauvel, Joseph Revealing Himself to His Brothers

From a Speculum historiale by Vincent of Beauvais

French (Paris), c. 1333-1334

Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France

MS Francais 316, fol. 75v |

,%20c.%201350_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Francais%201753,%20fol.%2024r.jpg) |

* Anonymous, Joseph Reveals Himself to His Brothers

From a Histoires bibliques

French (Saint-Quentin), c. 1350

Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France

MS Francais 1753, fol. 24r |

,%20c.%201353-1359_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Francais%20168,%20fol.%2068r.jpg) |

* Stefano di Alberto Azzi, Joseph Meeting His Brothers

From an Ancient History

Italian (Bologna), c. 1353-1359

Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France

MS Francais 168, fol. 68r |

,%20c.%201370-1380_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20NAF%2015939,%20fol.%2043r.jpg) |

* Master of the Livre du Sacre and Workshop, Joseph Meeting His Brothers

From a Speculum historiale by Vincent of Beauvais

French (Paris), c. 1370-1380

Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France

MS NAF 15939, fol. 43r |

The image of Egypt in Renaissance and Baroque works is of a fantasy land. The settings and costumes of the characters are neither clothing contemporary with the painter nor based on any historical model. They suggest a theatrical vision of the “East”.

Between 1515 and 1517 the painters Bacchiacca and Pontormo were commissioned to paint the story of Joseph on the walls of a room within a Florentine palace that were being decorated as a wedding gift for the owner and his new bride. Three of the paintings illustrated this last episode in the life of Joseph. All the paintings are now in the National Gallery in London.

,%20Joseph%20Reveives%20His%20Brothers_Italian,%20c.%201515_London,%20National%20Gallery.jpg) |

* Bacchiacca (Francesco d'Ubertino), Joseph Receives His Brothers

Italian, c. 1515

London, National Gallery |

,%20Joseph%20PardonsHis%20Brothers_Italian,%20c.%201515_London,%20National%20Gallery.jpg) |

* Bacchiacca (Francesco d'Ubertino), Joseph Pardons His Brothers

Italian, c. 1515

London, National Gallery |

|

+ Jacopo Pontormo, Joseph in Egypt

Italian, c. 1516

London, National Gallery |

|

* Workshop of Antoine Conrade after a Woodcut by Bernard Salomon, Joseph Forgives His Brothers

French, c. 1630-1645

New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

|

Giovanni Battista Gaulli (Baciccio), Joseph Recognized By His Brothers

Italian, c.1680

Ajaccio, Palais Flesch, Musee des Beaux-Arts |

|

Antoine Coypel, Joseph Recognized By His Brothers

French, c. 1730-1731

Paris, Mobilier Nationale |

|

* Franz Anton Maulbertsch, Joseph and His Brothers

Austrian, c. 1745-1750

Budapest, Szépmûvészeti Múzeum |

|

* Peter Cornelius, The Recognition of Joseph by His Brothers

German, c. 1816-1817

Berlin, Nationalgalerie |

Similar costuming could have applied to stories from Rome or Persia (with turbans). There is nothing very specifically Egyptian about them. In light of the fact that Egyptian antiquities were relatively well known in Europe between the fall of the Roman Empire and about 1800 (think of the obelisks in Rome, for instance) this is a bit puzzling. The evidence was there, it just wasn't being used.

Images After 1800

The visual image changes that occur after 1800, as exemplified by the undated painting of Joseph Recognized By His Brothers by Francois Gerard, are striking.

|

Francois Gerard, Joseph Recognized By His Brothers

French, c. 1800

Angers, Musee des Beaux-Arts |

Gerard is best known as the painter of the courts of Napoleon I and his Bourbon successors, Louis XVIII and Charles X. His career spans the first half of the 19th century. His Joseph inhabits a world with definite Egyptian details. There are sphinxes on the arms of his chair and above his head on the terrace of a building. He himself wears a nemes headdress. The difference, as they say, is in the details. But what has made the change? In a single word, Napoleon.

In July 1798 then-General Napoleon Bonaparte, at the orders of the Directory then running France following the disastrous years of the Revolution and the Reign of Terror, led a French army across the Mediterranean to land at Alexandria. The intent of the mission was to damage Britain by cutting into her trade routes through the ports of Palestine and the Levant. (The Suez Canal did not exist at this time, remember.) France simultaneously attempted to tie the British down in their home islands by sending an invasion force to Ireland (as part of the ill-fated 1798 rebellion there). All went well at first for Bonaparte. He won several battles over the Mamluk warriors who then held Egypt and took control of the country. He also conquered parts of Palestine.

|

Antoine-Jean Gros, Battle of the Pyramids

French, 1810

Versailles, Chateau

|

With the French army came scholars whose original intent had been to bring the Egyptians up to date with the Revolution, much as the French army had done in European countries that it had conquered in the years since 1789. However, these scholars soon fell under the spell of the older Egyptian civilization whose relics they saw all around them. Archaeology was then in its infancy, having begun more or less in earnest with the discovery of Pompeii in the late 18th century. It is they who began the study of ancient Egypt that resulted in the development of Egyptian archaeology. There were also artists among them who set to work sketching and painting the sights that they saw.

In August 1798 the French navy was virtually destroyed by Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson at the Battle of the Nile and the French army was thereby cut off from both resupply and wholesale evacuation from Egypt. Although continuing to function well for another year, it was eventually evident that they could not hope to keep control of the country for very long. So, as he would do again in 1812 in Russia, Napoleon decided to cut his own loses and publicize his victories in advance of eventual defeat. He quietly slipped out of Egypt back to France. He returned to a France in crisis. The Directory was near collapse and a coup was planned against it. His position as Victor over Egypt gave him brilliant notoriety and shortly after his return he became the leading member of the Consulate that replaced the deposed Directory. By the end of the year he was First Consul. He went on from there to become First Consul for Life and, finally, Emperor.

As for the French army and French scholars left behind in Egypt–their fate was less glorious. Without adequate resupply the army's ability to continue to hold Egypt diminished dramatically and Egypt was captured by the British in 1801. At that time many of the discoveries made by the scholars fell into the hands of the British, including the famous Rosetta Stone.

|

The Rosetta Stone

Egyptian, 196 BC

London, British Museum |

This stele with its text written in ancient hieroglyphs, in demotic Egyptian and in ancient Greek became the key to the problem of deciphering the hieroglyphs and is today in the British Museum, not the Louvre.

However, the information that did come back to France with the scholars and artists set off a craze for all things Egyptian and before long there were Egyptian tea services, Egyptian chairs, sphinx ornamented furniture, Egyptian themed jewelry. Frequently, items of Egyptomania sat side by side in the homes of the fashionable with equally important Roman Revival objects.

|

Charles Percier, Egyptian caryatid and design for decorative panel

French, c.1800

Paris, Musee du Louvre, Departement des Arts graphiques |

The fact that most of the artifacts found by Napoleon's scholars went to Britain set off a wave of similar Egyptomania there as well. It has been part of our world ever since, ebbing and flowing as new discoveries, such as the tomb of King Tutanhkamun, come to light.

In the realm of painting the Egyptian craze set in motion the search for the exotic that marks the work of so many painters from the second quarter of the 19th century onward. Painters were no longer content to merely imagine exotic locales. They went there to sketch. Examples abound in later 19th-century painting.

The Swiss-born Gleyre, the teacher of many of the major Impressionists, produced images such as the Egyptian Temple of 1840.

|

Charles Gleyre, Egyptian Temple

Swiss, 1840

Lausanne, Musee Cantonale des Beaux-Arts |

Jean-Leon Gerome went to Egypt in 1856 and, from his experiences there produced Napoleon Before the Sphinx.

|

Jean-Leon Gerome, Napoleon Before the Sphinx

French, 1867

San Simeon, CA, Hearst Castle |

The story of Joseph also received more realistic treatment. By the last decades of the 19th century paintings of his story are set in a recognizably ancient Egypt.

|

Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Joseph, Overseer of the Pharoah's Granaries

English, 1874

Private Collection |

Such pictures as Joseph, Overseer of the Pharaoh's Granaries by the Dutch-British artist, Lawrence Alma-Tadema,

and Joseph Reveals Himself to His Brothers by the Franco-British, James Tissot, inhabit an entirely different world from the Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque images.

|

+ James Tissot, Joseph Reveals Himself to His Brothers

French, c. 1896-1902

New York, The Jewish Museum |

Selected images refreshed and additional images added, 2025.

+ Indicates a refreshed image

-German,%201757_Baumberg,%20Church%20of%20Saint%20Margaret.jpg)

,%20Last%20Quarter%20of%20the%2013th%20Century_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Francais%2020125,%20fol.%2070r.jpg)

,%20c.%201333-1334_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Francais%20316,%20fol.%2075v.jpeg)

,%20c.%201350_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Francais%201753,%20fol.%2024r.jpg)

,%20c.%201353-1359_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Francais%20168,%20fol.%2068r.jpg)

,%20c.%201370-1380_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20NAF%2015939,%20fol.%2043r.jpg)

,%20Joseph%20Reveives%20His%20Brothers_Italian,%20c.%201515_London,%20National%20Gallery.jpg)

,%20Joseph%20PardonsHis%20Brothers_Italian,%20c.%201515_London,%20National%20Gallery.jpg)