|

| Bartolome Esteban Murillo, The Prodigal Receives His Inheritance Spanish, c. 1660-1665 Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland |

“Tax collectors and sinners were all drawing near to listen to Jesus,

but the Pharisees and scribes began to complain, saying,

“This man welcomes sinners and eats with them.”

So to them Jesus addressed this parable:

“A man had two sons, and the younger son said to his father,

‘Father give me the share of your estate that should come to me.’

So the father divided the property between them.

After a few days, the younger son collected all his belongings

and set off to a distant country where he squandered his inheritance on a life of dissipation.

When he had freely spent everything, a severe famine struck that country,

and he found himself in dire need.

So he hired himself out to one of the local citizens who sent him to his farm to tend the swine.

and he found himself in dire need.

So he hired himself out to one of the local citizens who sent him to his farm to tend the swine.

And he longed to eat his fill of the pods on which the swine fed, but nobody

gave him any.

Coming to his senses he thought, ‘How many of my father’s hired workers

have more than enough food to eat, but here am I, dying from hunger. I shall get up and go to my father and I shall say to him, “Father, I have sinned against heaven and against you.

I no longer deserve to be called your son;

treat me as you would treat one of your hired workers.”’

So he got up and went back to his father.

have more than enough food to eat, but here am I, dying from hunger. I shall get up and go to my father and I shall say to him, “Father, I have sinned against heaven and against you.

I no longer deserve to be called your son;

treat me as you would treat one of your hired workers.”’

So he got up and went back to his father.

|

| Peter Paul Rubens, The Prodigal Tending Swine Flemish, c. 1618 Antwerp, Koninklijk Museum voor Schoen Kunsten |

While he was still a long way off, his father caught sight of him, and was

filled with compassion.

He ran to his son, embraced him and kissed him.

His son said to him,

‘Father, I have sinned against heaven and against you;

I no longer deserve to be called your son.’

He ran to his son, embraced him and kissed him.

His son said to him,

‘Father, I have sinned against heaven and against you;

I no longer deserve to be called your son.’

But his father ordered his servants,

‘Quickly bring the finest robe and put it on him;

put a ring on his finger and sandals on his feet.

‘Quickly bring the finest robe and put it on him;

put a ring on his finger and sandals on his feet.

| |

|

Take the fattened calf and slaughter it.

Then let us celebrate with a feast, because this son of mine was dead, and has come to life again;

he was lost, and has been found.’

Then the celebration began.

Now the older son had been out in the field

and, on his way back, as he neared the house, he heard the sound of music and dancing.

He called one of the servants and asked what this might mean.

The servant said to him,

‘Your brother has returned

and your father has slaughtered the fattened calf

because he has him back safe and sound.’

He became angry, and when he refused to enter the house,

his father came out and pleaded with him.

He said to his father in reply,

‘Look, all these years I served you and not once did I disobey your orders;

yet you never gave me even a young goat to feast on with my friends.

But when your son returns who swallowed up your property with prostitutes,

for him you slaughter the fattened calf.’

He said to him,

‘My son, you are here with me always; everything I have is yours.

But now we must celebrate and rejoice,

because your brother was dead and has come to life again;

he was lost and has been found.’”

Then let us celebrate with a feast, because this son of mine was dead, and has come to life again;

he was lost, and has been found.’

Then the celebration began.

Now the older son had been out in the field

and, on his way back, as he neared the house, he heard the sound of music and dancing.

He called one of the servants and asked what this might mean.

The servant said to him,

‘Your brother has returned

and your father has slaughtered the fattened calf

because he has him back safe and sound.’

He became angry, and when he refused to enter the house,

his father came out and pleaded with him.

He said to his father in reply,

‘Look, all these years I served you and not once did I disobey your orders;

yet you never gave me even a young goat to feast on with my friends.

But when your son returns who swallowed up your property with prostitutes,

for him you slaughter the fattened calf.’

He said to him,

‘My son, you are here with me always; everything I have is yours.

But now we must celebrate and rejoice,

because your brother was dead and has come to life again;

he was lost and has been found.’”

The story of the Prodigal Son is one of the best known of the parables of Jesus. It describes the way in which God is always willing to forgive the penitent sinner in human and understandable terms and reminds those who “are with me always” to welcome the sinner in the same way.

In art, the Father’s

welcome of his wayward son in an image such as Rembrandt’s is so frequently

seen that we may stand in danger of overlooking it because of its familiarity.

|

| Rembrandt van Rijn, Return of the Prodigal Son Dutch, c. 1669 St. Petersburg, Hermitage Museum |

So, let us examine the ways in which this

image developed and what other images of the topic may exist.

In preparation for this essay I did an extensive survey of the prodigal son images available on the internet for inclusion in this blog. The images available come predominantly from the north of Europe. I was able to find some Italian pictures but the quality of many of the available images from these sites is not very good. Consequently, most images included in this essay will come from Northern Europe, where the subject was a very popular one, especially in the Renaissance and Baroque periods.

Telling the Story

In the medieval period the most commonly seen images of the

prodigal son told the entire story from St. Luke. The images appeared in manuscripts and in

sculpture and most especially in stained glass windows, of which there is a

series in France.

|

| Parable of the Prodigal Son, Single leaf from a Psalter English (Canterbury), c. 1155-60 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M 521 |

%20from%20an%20Ivory%20Casket_French%20(Paris),%20c.%201250-1270_Louvre,%20D%C3%A9partement%20des%20Objets%20d'art%20du%20Moyen%20Age,%20de%20la%20Renaissance%20et%20des%20temps%20modernes.JPG) | |

The Prodigal Spends His Money on Riotous Living

|

|

| Scenes from the Story of Prodigal Son French, c. 1301-1400 Auxerre, Cathedral of Saint Etienne |

|

| The Prodigal Son Feasting (detail from Story of the Prodigal Son) French, c. 1301-1400 Auxerre, Cathedral of Saint Etienne |

|

| Prodigal Son Window French, 13th Century Bourges, Cathedral of St. Etienne 1 |

|

| Prodigal Son Window French, 13th Century Chartres, Cathedral |

In the windows

especially, probably because of their greater size, scenes are included that

are not found in the Gospel account.

These scenes elaborate parts of the story that are barely described in

the Gospel, usually having to do with the dissipated life led by the prodigal

after leaving his family and his subsequent collapse.

Among the invented scenes are those of the prodigal

enjoying the company of prostitutes, playing games of chance, being thrown out

of the town once his money is gone, even being set on by thieves.

|

| Prodigal Son Window French, 13th Century Sens, Cathedral |

A series of eight German grisaille painted glass window roundels from 1532, displayed at the Cloisters branch of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, shows many of these scenes.

|

| The Prodigal Says Farewell German, 1532 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

|

| The Prodigal Gambles German, 1532 New York, Metropolitan Museum |

|

| The Prodigal Seeks Work German, 1532 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

|

| The Prodigal Works As a Swineherd German, 1532 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

|

| The Prodigal Is Given the Best Robe German, 1532 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

Additional scenes may be added regarding his

homecoming as well, especially around the preparation of the celebratory

feast. Many of these embellishments had a long

afterlife in art. 1

|

| The Return of the Prodigal Is Celebrated German, 1532 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

Artists found many ways to tell the entire story. Among these are a series of scenes, like the windows above, or the inclusion of all the aspects of the story in one picture, such as those below.

Many seventeenth-century embroidery projects featured multiple aspects of this story.

The Typological Approach

Another medieval way of telling the story was the

typological approach, which we have seen before. The Biblia pauperum or Bible of the Poor, was

one of the most frequently read books among the laity of the late medieval

period. Generally speaking this book

showed relationships between the stories of the Old Testament and the New Testament

in the form of types, in which the New Testament scene is related to two Old

Testament scenes. The scenes chosen to

relate to the image of the penitent prodigal son are a little different.

|

| Master of the Hours of Margaret of Cleves Dutch, c. 1405 London, British Library MS King's 5, fol. 24 |

Instead of two Old Testament scenes related

to one New Testament scene we see that there is one Old Testament scene, one

New Testament parable and one scene from the life of Christ. The scenes chosen are all those that involve

joyful returns. The Old Testament scene

is the meeting between Joseph and his brothers, the New Testament parable scene

is the return of the Prodigal Son and the scene from the life of Christ is the

meeting between the Risen Christ and his disciples.

|

| Rambures Master, Biblia Pauperum French (Amiens or Hesdin), c. 1470 The Hague, Museum Meermano-Westreenianum MS MMW 10 A 15, fol. 35v |

In the Renaissance and later periods the number of

illustrations of the parable of the Prodigal Son virtually exploded. It was particularly popular in the Low

Countries (Belgium and the Netherlands), France and Spain. But there is a subtle difference in what each

region focused on.

Degradation

Painters in the Low Countries tended to focus on the riotous

life of the prodigal after leaving home. Scenes of drunken merriment abound. Since the figures depicted are invariably shown wearing contemporary clothing, these scenes can perhaps best be seen as contemporary social comment dressed in a Biblical disguise.

|

| Jan van Hemessen, The Prodigal Son Flemish, 1536 Brussels, Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts |

|

| Joachim Beuckelaer, The Four Elements-Air Flemish, 1570 London, National Gallery The carousing Prodigal Son appears in the background. |

|

| Palma Giovane, Amusements of the Prodigal Son Italian, c. 1595-1600 Venice, Gallerie dell'Accademia |

|

| Gerrit van Honthorst, Prodigal Son Dutch, 1622 Munich, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Alte Pinakotek |

|

| Frans Francken II, Prodigal Son With Courtesans Flemish, c. 1630s Private Collection |

|

| Gabriel Metsu, Prodigal Son Dutch, 1640s St. Petersburg, Hermitage Museum |

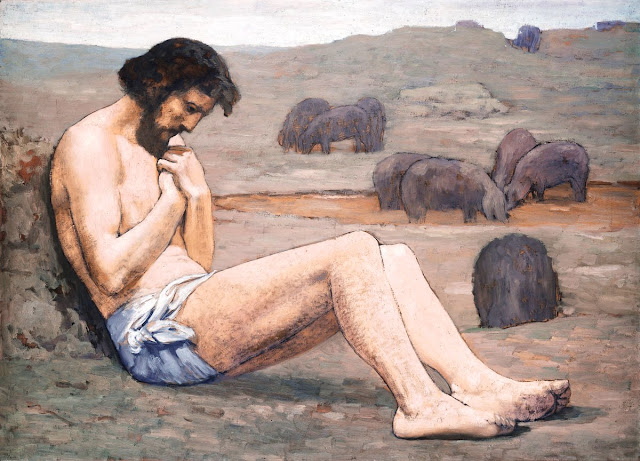

Realization and Sorrow

His degradation as his funds evaporated, the misery of his life as a swineherd and his realization of his sins seem to have been more popular with Flemish, Spanish and French

painters.

|

| Peter Paul Rubens, The Prodigal Son Flemish, c. 1651-1655 St. Petersburg, Hermitage Museum |

|

Bartolome Esteban Murillo, The Prodigal Son Driven Out of Town

Spanish, 1660s

Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland |

|

| Bartolome Esteban Murillo, The Prodigal Son Tending the Swine Spanish, 1660s Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland |

|

| Anonymous, The Prodigal Son Tending the Swine French, Early 19th Century Chambery, Musée des Beaux-Arts |

|

| Paul Vayson, Prodigal Son Tending the Swine French, c. 1875-1900 Bordeaux, Musée des Beaux-Arts |

|

| Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Prodigal Son Tending the Swine French, c. 1879 Washington, National Gallery of Art |

|

| Auguste Rodin, The Prodigal Son French, 1905 Paris, Musée Rodin |

The Forgiving Father

However, it is the image of the actual return of the sorrowful, penitent son to the loving embrace of his father that has inspired the majority of artists over the centuries. |

| Illuminated Manuscript Initial, Return of the Prodigal Italian, 16th Century New York, Brooklyn Museum |

|

| Jacopo and Francesco Bassano, Return of the Prodigal Italian, c. 1570 Madrid, Museo del Prado |

|

| Guercino, Return of the Prodigal Son Italian, 1619 Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum |

|

| Domenico Fetti, Return of the Prodigal Italian, ca 1620 Dresden, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen |

|

| Simon de Vos, Homecoming of the Prodigal Son Flemish, 1641 Munich, Hampel Kunstauktionen |

|

| Johann Carl Loth, Return of the Prodigal Son German, 1647-1698 Vienna, Dorotheum |

|

| Bartolome Esteban Murillo, Return of the Prodigal Son Spanish, 1660s Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland |

|

| Jan Steen, Return of the Prodigal Son Dutch, 1668-1669 Private Collection |

|

| Peter Brandl, Return of the Prodigal Son Czech, c.1700 Boston, Museum of Fine Arts |

|

| Nicholas Vleughels, Return of the Prodigal Son French, 1709 Private Collection |

|

| Augustin Louis Belle, Return of the Prodigal Son, French, 1782 Lille, Musée des Beaux-Arts |

|

| Stanislas-Henri-Benoit Darondeau, Return of the Prodigal Son French, 1840 Private Collection |

|

| Alexander Maximilian Seitz, Return of the Prodigal Son German, 1858 Rome, Church of Santissima Trinita dei Monti |

|

| James Tissot, Return of the Prodigal Son French, c. 1886-1894 New York, Brooklyn Museum |

There is curiously little difference between the iconography of the various scenes among all these painters. Some have tried to see differences between images produced in the Catholic countries (Belgium, France, Spain and Italy) and those produced in the Protestant countries (The Netherlands and Germany), but these efforts seem pointless.

Though there may have been differences in the interpretation of the Biblical text between Protestant and Catholic theologians, primarily due to the different approaches to the workings of grace in the penitent soul, there is virtually no difference in how the artists of the two traditions painted the scene of the penitent’s return.2

Rembrandt’s image of the loving father and the penitent son is as acceptable to a Catholic as to a Protestant viewer.

© M. Duffy, 2016

_____________________________________________________________

1. 1.

For details regarding the layout of these

windows see the following websites:

·

Bourges: file:///J:/ART/Parables/Prodigal%20Son/Whole%20story/Bourges%20cathedral%20stained%20glass.html

·

Chartres: file:///J:/ART/Parables/Prodigal%20Son/Whole%20story/Chartres%20Cathedral%20stained%20glass.htm

2. Haeger, Barbara.

“The Prodigal Son in Sixteenth and Seventeenth-Century Netherlandish

Art: Depictions of the Parable and the

Evolution of a Catholic Image”, Simiolus:

Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art, Vol. 16, No. 2/3 (1966),

pp. 128-138.

Scripture texts in this

work are taken from the New American Bible, revised edition© 2010,

1991, 1986, 1970 Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, Washington, D.C. and are

used by permission of the copyright owner. All Rights Reserved. No part of the

New American Bible may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing

from the copyright owner.

,%20c.%201250-1270_Louvre,%20D%C3%A9partement%20des%20Objets%20d'art%20du%20Moyen%20Age,%20de%20la%20Renaissance%20et%20des%20temps%20modernes.JPG)

%20from%20an%20Ivory%20Casket_French%20(Paris),%20c.%201250-1270_Louvre,%20D%C3%A9partement%20des%20Objets%20d'art%20du%20Moyen%20Age,%20de%20la%20Renaissance%20et%20des%20temps%20modernes.JPG)

No comments:

Post a Comment