,%20Biblioteca%20Documenta%20Batthyaneum_MS%20R%20II%201,%20fol.%2072v.jpg) |

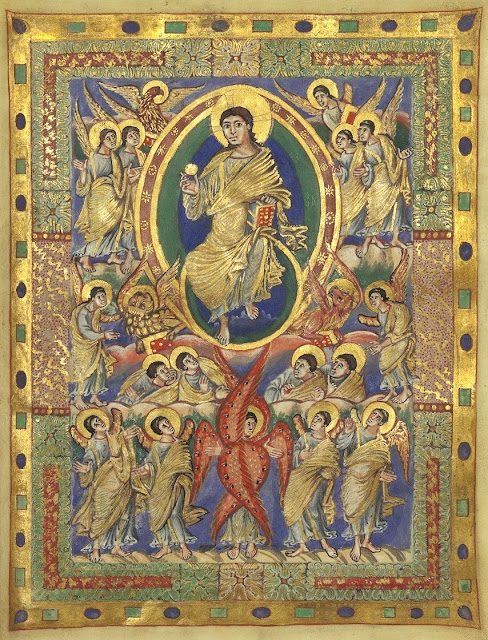

| Christ in Majesty, Codex Aureus of Lorsch German, c. 778-830 Alba Julia (RU), Biblioteca Documenta Batthyaneum MS R II 1, fol. 72v |

"When the Son of Man comes in his glory,

and all the angels with him,

he will sit upon his glorious throne,

and all the nations will be assembled before him.

And he will separate them one from another,

as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats."

Matthew 25:31-32

Portion of Gospel for the Solemnity of Christ the King,

Year A

The idea of Jesus as king of the universe goes back to the earliest decades of Christian life. In Philippians 2:9-11, written sometime between 55 and 63 AD, St. Paul quotes what is believed to be one of the earliest Christian hymns which proclaims “Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father” at whose name “every knee should bend, of those in heaven and on earth and under the earth” (Philippians 2:11 and 10).

In Christian art, however, the visual representation of Christ as King and Lord of the universe took a while to develop. It was not until the 4th century, when Christianity had become a tolerated religion and was free to construct buildings specifically for Christian worship, that this image began to appear. Earlier, images of Christ, made during the days of persecution and a need for concealment, had been symbolic (such as the well-known sign of the fish) or had been disguised (as for instance, the image of the Good Shepherd or the Philosopher). 1 With the easing of these pressures, and the accompanying sudden acquisition of Imperial favor and Imperial involvement; as well as in the course of thrashing out the Church’s understanding of the nature of Jesus as both human and divine, these images were superseded by others which reflected the kingly understanding already apparent in the hymn quoted by St. Paul.

Developing the Iconography

The obvious place to which 4th century Christians looked for ideas in how to portray the human-divine person of Jesus as King was to already existing images of the Emperor. These images went back as far as the time of Augustus in the early 1st century (as for instance in the Augusta Primaporta).

|

| Augustus Primaporta, Roman, 1st century Vatican, Vatican Museums, Braccio Nuovo |

But they were also as recent as Constantine’s own colossal statue of around 315. This gigantic statue, original parts of which can be seen today in the Capitoline Museum in Rome, was placed around 315 in the secular basilica, now known as the Basilica of Constantine, close to the Coliseum. Modeled on the famous colossal statue of the god, Zeus, at Olympus, it showed Constantine seated, holding a scepter in his upraised right hand. Reconstructions have suggested that he held an orb in his now missing left hand. In 2024 an actual reconstruction was created, using digital images of the original parts and using best guess digital reconstructions of the parts that have not survived. This reconstruction has been placed in a garden that is part of the Capitoline Museum area and the effect is astonishing. This is definitely an overwhelming image of power and glory.

|

| Reconstruction of Colossal Statue of Constantine Italian, 2024 Rome, Capitoline Museum, Giardino di Villa Caffarelli |

This image will be on display in the garden until at least the end of 2025.

It is, therefore, not surprising that the earliest images of Christ as King portray Him in a similar way. In one of the two apse mosaics from the tomb of Constantine’s daughter, Constantina, dated to around 350, Christ appears as if an Emperor. As described by Prof. Johannes Deckers “Christ is portrayed as Pantocrator, enthroned atop a transparent blue sphere symbolizing the cosmos. Although he still wears the traditional costume of a philosopher, consisting of tunic, cloak and sandals, now his garments are either gold or purple adorned with wide gold stripes like those of the emperor. His bearded head is surrounded by a nimbus, a device employed in earlier Roman art to distinguish gods, personifications, and deified emperors. Christ hands Peter a pair of keys symbolic of the powers entrusted to him. Peter receives the keys in humility, his hands draped in his cloak. …. it is as though we are witnessing a ceremony at the court of the emperor of heaven. Peter approaches Christ in the way etiquette demanded that an official approach the emperor on receiving an appointment. .. Christ appears like the lord of heaven between fiery clouds, enthroned above the spherical cosmos. To see how explicitly Christ is cast in the role of n emperor, one need only glance at a traditional formula adapted for various rulers in Roman times.”2

|

| Christ in Majesty Mosaic Roman, c. 350 Rome, Church of Santa Costanza |

However, there are also significant differences between the image of Christ and the image of the Emperor for Christ holds, not a scepter and an orb, but keys and a scroll, very much as He had in the image of the Traditio Legis. He is not the worldly ruler, but a ruler whose kingdom is one of heavenly power, based on the Scriptures.

A few decades later, in the last decade of the 4th century, the Roman church of Santa Pudenziana was decorated with an apse mosaic in which the theme of Christ as ruler is still close to that of the Emperor. This image shows Christ, seated on a throne and surrounded by the Apostles, as well as by two female figures that may represent the Old and New Testaments.

,%20c.%20380-400_Rome,%20Church%20of%20Santa%20Pudenziana.jpg) |

| Christ in Majesty Mosaic Roman, c. 400 Rome, Church of Santa Pudenziana |

Compositionally, it is not unlike the silver plate, called the Missorium of Theodosius I, which is almost exactly contemporary. However, again there are points of departure between the images. In Santa Pudenziana, Christ once again holds a document which now begins to resemble a codex (a bound book, instead of a scroll) and His right hand begins to assume a blessing gesture.

|

Silver Plate known as the Missorium of Theodosius I Roman, c. 388 Madrid, Academia Real de Historia |

In the image used in the sixth century church of San Vitale in Ravenna, at that time the Italian capital of the emerging Byzantine Empire (based in Constantinople, today's Istanbul) Christ again holds a scroll or possibly a codex in his left hand, while presenting the wreath of heavenly victory to the emperor, who is presented to him by an angel.

Byzantine Tradition

These late antique images formed the basis for the image of the Christ Pantocrator, which became widespread in Byzantine and Byzantine-derived works.

The earliest known image of the specific type known as the Pantocrator comes from the sixth century, from the monastery of Saint Catherine at Sinai. It is a more focused view of the upper body of Christ, which appears to derive from the Christ in Majesty figures in the earlier mosaic works.

,%20Saint%20Catherine's%20Monastery.jpg) |

| Earliest Known Image of Christ as Pantocrator Byzantine, 6th Century Sinai (Egypt), Saint Catherine's Monastery |

This became the favored image for the Byzantine world, frequently appearing in mosaic form wherever the Greek Church was established, as far west as southern Italy and Sicily and in the Greek derived Churches of Eastern Europe and Russia.

|

| Apse Mosaic Byzantine, 1148 Cefalu (Sicily), Cathedral |

|

| Apse Mosaic Byzantine, c. 1180-1190 Monreale (Sicily), Cathedral |

.jpg) |

| Icon of Christ Pantocrator Russian, 1363 Saint Petersburg, State Hermitage Museum |

However, the Byzantine tradition also continued to use image of a full-scale seated Christ as well.

,%20c.%201131-1143_London,%20British%20Library_MS%20Egerton%201139,%20fol.%2012v.jpg) |

| Basilius, The Deesis From the Melisande Psalter Byzantine (Jerusalem), c. 1131-1143 London, British Library MS Egerton 1139, fol. 12v |

|

| Ascension with Christ in Majesty From a Gospel Book Eastern Mediterranean, Possible Cyprus or Palestine, c. 1175-1250 London, British Library MS Harley 1810, fol. 135v |

|

| Deesis Mosaic Byzantine, c. 1260-1270 Istanbul, Hagia Sophia |

|

| Elias Moskos, Christ in Majesty Greek, 1653 Recklinghausen, Ikonen-Museum |

Medieval Europe

By the middle ages, in what had been the western half of the Roman Empire, the image of the seated Christ, holding a codex and blessing appeared in many media, large and small scale. These included book covers, book illustrations, sculpture, wall paintings and metalwork. Examples come from all over the Christian west.

,%20c.%20781-783_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Nouvelle%20acquisition%20latine%201203,%20fol.%203r.jpeg) |

| Christ in Majesty From the Gospel Book of Godescalc German (Rheinland), c. 781-783 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Nouvelle acquisition latine 1203, fol. 3r |

,%20c.%20800_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Latin%208850,%20fol.%20124r.jpeg) |

| Christ in Majesty and the Visitation From the Gospels of Saint-Médard de Soissons German (Aachen), c. 800 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 8850, fol. 124r |

,%20c.%20849-851_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Latin%20266,%20fol.%202v.jpeg) |

| Christ in Majesty From the Gospels of Lothair French (Tours), c. 849-851 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 266, fol. 2v |

|

| Christ in Majesty with Prophets and Evangelists From the Codex Aureus of Saint Emmeram French, c. 870-879 Munich, Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek MS Cod. lat. 14000, fol. 6v |

|

| Christ in Majesty From the Sacramentary of Charles the Bald French, c. 870 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 1141, rol. 5r |

|

| Christ in Majesty From the Benedictional of Aethelwold English, c. 963-984 London, British Library MS Additional 49598, fol. 70r |

,%20c.%20984_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Latin%208851,%20fol.%201v.jpeg) |

| Christ in Majesty Surrounded by the Evangelists and their Symbols From the Gospels of the Sainte-Chapelle German (Treves), c. 984 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 8851, fol. 1v |

|

| Christ in Majesty Ivory, German, 11th century New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

By the beginning of the eleventh century (1000-1100) the image of Christ in Majesty was widespread. Christ is seated on a throne instead of the globe, most often he holds a book in one hand and makes a gesture of blessing with the other. He is usually surrounded by a mandorla, around which there may be angels, the evangelists or their symbols, and sometimes prophets and saints.

,%20c.%201010_Bamberg,%20Staatsbibliothek%20Bamberg_MS%20Msc.Bibl.140_fol.%2047v.jpg) |

| The Great Alleluia From the Bamberg Apocalypse German (Reichenau), c. 1010 Bamberg, Staatsbibliothek Bamberg MS Msc.Bibl.140, fol. 47v |

|

| Lintel with Christ in Majesty French, c. 1019-1020 Saint-Genis-des-Fontaines, Abbey Church |

|

| Capital with Christ in Majesty French, c. 1050 Paris, Musée de Cluny, Musée nationale du Moyen Âge |

|

| Christ in Majesty Tympanum of the West Portal French, c. 1090 Charlieu, Church of Saint-Fortunat |

|

| Christ in Majesty From the Shaftesbury Psalter English, c. 1125-1150 London, British Library MS Landsdowne 383, fol. 14v |

During the twelfth and thirteenth centuries the city of Limoges in south-central France (long been famous for its enamelwork on copper and continuing this tradition of enamel painting to this day through its famous porcelain factories) produced what must have been thousands of variations on this image for use in portable altars, covers for liturgical books and other liturgical equipment.

In 2022 I found that the manuscript illuminators of medieval Limoges produced virtually identical works. This suggests that there was a commonly agreed upon model for producing this image in the city.

,%2012th%20Century_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Latin%209438,%20fol.%2058v.jpeg) |

| Christ in Majesty From a Missal French (Limoges), 12th Century Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 9438, fol. 58v |

,%20c.%201175-1200_Paris,%20Musee%20de%20Cluny,%20Musee%20national%20du%20Moyen%20Age.jpg) |

| Christ in Majesty French (Limoges), c. 1175-1200 Paris, Musée de Cluny, Musée nationale du Moyen Âge |

|

| Book-Cover Plaque with Christ in Majesty French (Limoges), c. 1185-1210 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

|

| Book-Cover Plaque with Christ in Majesty French (Limoges), c. 1200 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

,%20c.%2012th-13th%20Century_London,%20British%20Library_MS%20Additional%2027926.jpg) |

| Enamel Cover of Gospel Book with Christ in Majesty French (Limoges), c. 12th-13th Century London, British Library MS Additional 27926 |

|

| Christ in Majesty Enamel book cover plaque French, Limoges, early 13th century New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

,%2013th%20Century_Vatican%20City,%20Musei%20Vaticani.png) |

| Plaque from a Book Cover with Christ in Majesty French (Limoges), 13th Century Vatican City, Musei Vaticani |

These works from Limoges were spread all over Europe and must have had a very great influence on the artists in the countries that received their objects.

,%20c.%201300_London,%20British%20Library_MS%20Royal%202%20A%20XXII,%20fol.%2014r.jpg) |

| Christ in Majesty From the Westminster Psalter English (Westminster or St. Albans), c. 1300 London, British Library MS Royal 2 A XXII, fol. 14r |

,%20c.%201210_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Latin%20238,%20fol.%2030v.jpeg) |

| Christ in Majesty From a Psalter French (North French), c. 1210 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 238, fol. 30v |

|

| Christ in Majesty From Psalter of Saint Louis and Blanche of Castille French, c. 1225 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Arsenal 1186, fol. 28r |

|

| Christ in Majesty From the Portada del Sarmental Spanish, c. 1235 Burgos, Cathedral |

,%20c.%201285-1290_Patis,%20BNF_MS%20Nouvelle%20acquisition%20francaise%2016251,%20fol.%2051v.jpeg) |

| Christ in Majesty From Images de la vie du Christ et des saints Flemish (Hainaut), c. 1285-1290 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Nouvelle acquisition francaise 16251, fol. 51v |

,%20c.%201300-1325_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Francais%20160,%20fol.%201r.jpeg) |

| Christ in Majesty From Bible historiale by Guiard des Moulins French (Paris), c. 1300-1325 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 160, fol. 1r |

,%20c.%201310-1320_London,%20British%20Library_MS%20Royal%202%20B%20VII,%20fol.%20298v.jpg) |

| The Queen Mary Master, Christ in Majesty From the Queen Mary Psalter English (Westminster), c. 1310-1320 London, British Library MS Royal 2 B VII, fol. 298v |

,%20c.%201323-1326_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20latin%2010483,%20fol.%20213r.jpg) |

| Atelier of Jean Pucelle, Christ in Majesty From the Breviary of Belleville French (Paris), c. 1323-1326 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS latin 10483, fol. 213r |

,%20c.%201330-1340_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Italien%20115,%20fol.%204r.jpeg) |

| Christ in Majesty From Meditationes vitae Christi Italian (Siena), c. 1330-1340 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Italien 115, fol. 4r |

,%20c.%201350-1375_London,%20British%20Library_MS%20Additional%2022310,%20fol.%2010%20(2).jpg) |

| Niccolo di Giacomo di Nascimbene, aka Niccolo da Bologna, Christ in Majesty with Saints Cutting from a Choir Book Italian (Bologna), c. 1350-1375 London, British Library MS Additional 22310, fol. 10 |

,%20c.%201398-1403%20&%201420-1430_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Rothschild%202529,%20fol.%20104v%20(3).jpeg) |

| Christ in Majesty From the Breviary of Martin of Aragon Spanish (Catalonia), c. 1398-1403 & 1420-1430 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Rothschild 2529, fol. 104v |

,%201460_The%20Hague,%20KB_MS%20KB%2072%20A%2023,%20fol.%2011v%20(2).jpg) |

| Christ in Majesty with the Twelve Elders From the Liber Floridus by Lambert de Saint-Omer Flemish (Lille), 1460 The Hague, Koninklijk Bibliotheek MS KB 72 A 23, fol. 11v |

The Renaissance

The Renaissance period brought some changes to the use of the image of Christ in Majesty.

For one thing, it returned to use as a decoration for the semi-domes of the churches that were being built according to classical principles, first as a continuation of the mosaic tradition and later in newly realistic paintings.

|

| Apse Mosaic of Christ in Majesty Italian, 1297 Florence, Church of San Miniato al Monte |

|

| Boccaccio Boccaccino, Christ in Majesty with the Patron Saints of Cremona Italian, 1506 Cremona, Cathedral |

And it appeared in the newly introduced form of panel paintings.

|

| Giotto, The Stefaneschi Triptych Italian, c. 1330 Vatican City, Pinacoteca Vaticana |

|

| Hans Memling, Christ in Majesty Surrounded by Angels Center of triptych Netherlandish, 1480s Antwerp, Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten |

The Tradition Continues

This visual tradition leads right up to the 20th century, with the huge mosaic of Christ in Majesty in the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D. C., executed by Jan Henryk de Rosen, completed in 1959. |

| Jan Henryk de Rosen, Christ in Majesty Polish, 1959 Washington, D.C., National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception |

On December 11, 1925, at the conclusion of the 1925 Holy Year, Pope Pius XI established the feast of the Kingship of Our Lord Jesus Christ, with his encyclical, Quas Primas (The first (encyclical) which). In the encyclical Pius XI traced the roots of the title in the Bible and in Sacred Tradition and its meaning for the entire world. He fixed the date of the feast “on the last Sunday of the month of October - the Sunday, that is, which immediately precedes the Feast of All Saints”.3

On February 14, 1969, following Vatican Council II, Pope Paul VI in his motu proprio, Mysterii paschalis (The Paschal Mystery), promulgated a revised calendar of liturgical celebrations for the universal Church.4 As one of the revisions the Solemnity of Christ the King was moved to its present location of the last Sunday in Ordinary Time, as a fitting way to mark the close of the Church’s liturgical year. This move gave to the feast a slightly different, more cosmic, emphasis, an emphasis that had, in fact, been latent in the image of Christ in Majesty for centuries. For, at this time of the year, that is in the weeks leading up to and including the first Sunday of Advent (the Sunday which begins the new liturgical year), we are presented with readings that deal with the end of time and the final judgment of the world when, at His second coming, Christ will return to judge the world. Therefore, the image of Christ as King of the Universe and Lord of Time, with its undertones of relationship to scenes of the Last Judgment has found a match in the liturgical feast.

___________________________________________

1. Spier, Jeffrey; Fine, Steven; Charles-Murray, Mary; Jensen, Robin M.; Deckers, Johannes G. and Kessler, Herbert L. Picturing the Bible: the Earliest Christian Art, Catalog of the exhibition held at the Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, TX, November 28, 2007-March 30, 2008, New Haven, Yale University Press, 2007, pp. 13, 51-64. For information on this past exhibition see https://www.kimbellart.org/Exhibitions/Exhibition-Details.aspx?eid=47

2. Spier, et al., p. 95.

3. http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/pius_xi/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-xi_enc_11121925_quas-primas_en.html

4. http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/paul_vi/motu_proprio/documents/hf_p-vi_motu-proprio_19690214_mysterii-paschalis_en.html

© M. Duffy, Originally published, 2011.

On February 14, 1969, following Vatican Council II, Pope Paul VI in his motu proprio, Mysterii paschalis (The Paschal Mystery), promulgated a revised calendar of liturgical celebrations for the universal Church.4 As one of the revisions the Solemnity of Christ the King was moved to its present location of the last Sunday in Ordinary Time, as a fitting way to mark the close of the Church’s liturgical year. This move gave to the feast a slightly different, more cosmic, emphasis, an emphasis that had, in fact, been latent in the image of Christ in Majesty for centuries. For, at this time of the year, that is in the weeks leading up to and including the first Sunday of Advent (the Sunday which begins the new liturgical year), we are presented with readings that deal with the end of time and the final judgment of the world when, at His second coming, Christ will return to judge the world. Therefore, the image of Christ as King of the Universe and Lord of Time, with its undertones of relationship to scenes of the Last Judgment has found a match in the liturgical feast.

Christus vincit, Christus regnat, Christus imperat!

1. Spier, Jeffrey; Fine, Steven; Charles-Murray, Mary; Jensen, Robin M.; Deckers, Johannes G. and Kessler, Herbert L. Picturing the Bible: the Earliest Christian Art, Catalog of the exhibition held at the Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, TX, November 28, 2007-March 30, 2008, New Haven, Yale University Press, 2007, pp. 13, 51-64. For information on this past exhibition see https://www.kimbellart.org/Exhibitions/Exhibition-Details.aspx?eid=47

2. Spier, et al., p. 95.

3. http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/pius_xi/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-xi_enc_11121925_quas-primas_en.html

4. http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/paul_vi/motu_proprio/documents/hf_p-vi_motu-proprio_19690214_mysterii-paschalis_en.html

© M. Duffy, Originally published, 2011.

Revised with additional material and new images, 2022.

Additional material added 2024.

1 comment:

The remnants of the statue of Constantine - marble or bronze - are not at the Vatican Museums. They are at the Capitoline Museums.

Post a Comment