|

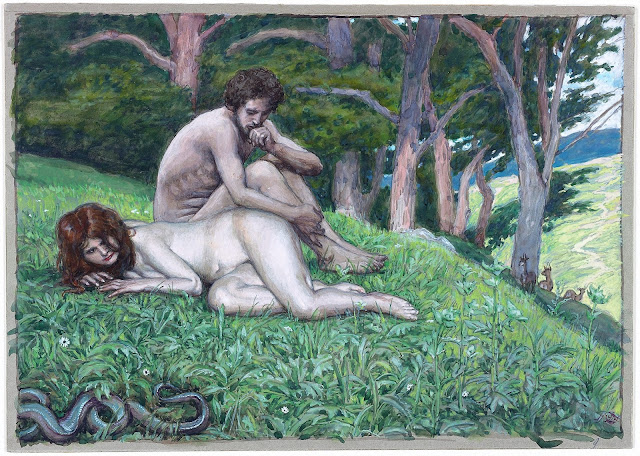

+Hans Holbein the Younger, Adam and Eve German, 1517 Basel, Kunstmuseum |

"The LORD God formed man out of the clay of the ground

and blew into his nostrils the breath of life,

and so man became a living being.

Then the LORD God planted a garden in Eden, in the east,

and placed there the man whom he had formed.

Out of the ground the LORD God made various trees grow

that were delightful to look at and good for food,

with the tree of life in the middle of the garden

and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.

and blew into his nostrils the breath of life,

and so man became a living being.

Then the LORD God planted a garden in Eden, in the east,

and placed there the man whom he had formed.

Out of the ground the LORD God made various trees grow

that were delightful to look at and good for food,

with the tree of life in the middle of the garden

and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.

Now the serpent was the most cunning of all the animals

that the LORD God had made.

The serpent asked the woman,

"Did God really tell you not to eat

from any of the trees in the garden?"

The woman answered the serpent:

"We may eat of the fruit of the trees in the garden;

it is only about the fruit of the tree

in the middle of the garden that God said,

'You shall not eat it or even touch it, lest you die.'"

But the serpent said to the woman:

"You certainly will not die!

No, God knows well that the moment you eat of it

your eyes will be opened and you will be like gods

who know what is good and what is evil."

The woman saw that the tree was good for food,

pleasing to the eyes, and desirable for gaining wisdom.

So she took some of its fruit and ate it;

and she also gave some to her husband, who was with her,

and he ate it.

Then the eyes of both of them were opened,

and they realized that they were naked;

so they sewed fig leaves together

and made loincloths for themselves.”

Genesis 2:7-9, 3:1-7

Continuing the series of posts on the first stories of the

Book of Genesis, we will look at the images corresponding to this reading from

the first Sunday of Lent for year A, which we are currently in.

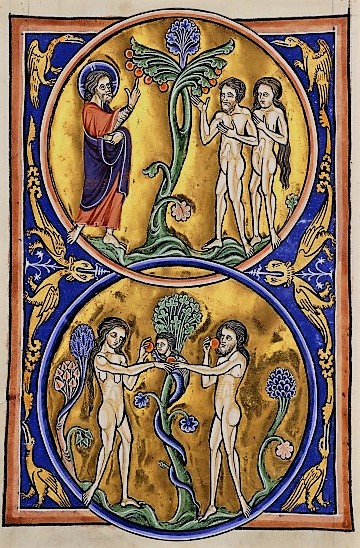

Scenes from the Book of Genesis

From the Psalter-Hours of Guiluys de Boisleux

French (Arras), c. 1246-1260

New York, Pierpont Morgan Library

MS M730, fol. 10r

|

After God created

the world and filled it with abundant resources and animal inhabitants (Genesis

1:1-25) He created two other creatures, a man, called Adam, and a woman, called

Eve

by the man (Genesis 1:26-31).

He gave

them a beautiful place, a garden, to live in (Genesis 2: 8) and told them they

could eat any of the fruit of any of the trees, except one, just one.

They promised to obey this request and seemed

innocent and happy to comply with this one restriction (Genesis 2:24-25).

|

| Adam and Eve Promise God Not To Eat of the Tree From Weltchronik German, c. 1355-1365 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M769, fol. 14r |

But, God had also given these creatures a little something

else, not mentioned specifically in the Bible, but there nevertheless, because

it is one of the things that separates them from the other creatures. This is Free Will. The pledge they took to respect God's command was given from their Free Will. However, since their Will is Free, the pledge could be broken as well as given. It just needed the right temptation.

Enter the Tempter. Also in the garden was a serpent. Traditionally this ‘serpent’ is imaged as Lucifer, the fallen archangel, the one who

rejected obedience to God’s will and was ejected from heaven (Revelation 12:

7-9) and whose sole existence has become rage at God and efforts to subvert

God’s work.

|

| The Serpent Tempts Adam and Eve From Weltchronik German (Regensburg), c. 1355-1365 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M769, fol.13r |

In art this ‘serpent’ is frequently seen as a snake

with a human face. This ‘cunning’ creature seduces Eve to taste

of the fruit of the Tree of Life with the promise that ‘you will be like gods, who know good and evil’ (Genesis 3:5). This is not a lie, but it also does not

exactly mean what it sounds like it means.

Eve naively assumes the surface meaning and displays the desire to be ‘like gods”. She eats and then persuades Adam to eat.

As soon as both have eaten, they realize the terrible error they have committed through their desire to ‘be like gods’. They have disobeyed the God who created them and now understand what His words meant, for they ‘know good and evil’. They know that they have done wrong, committed the sin of disobedience, and they recognize their changed condition for ‘the eyes of both of them were opened, and they knew that they were naked; so they sewed fig leaves together and made loincloths for themselves.‘ (Genesis 3:7)

|

| *Circle of the Coetivy Master, Adam and Eve Realize What They Have Done From a Speculum humanae salvationis French (Paris), c. 1450-1460 Einsiedeln, Stiftsbibliothek MS Cod. 206(49), page 6 |

The story continues.

When they heard “God walking about in the garden at the

breezy time of the day, the man and his wife hid themselves from the LORD God

among the trees of the garden.

The LORD God then called to the man and

asked him: Where are you?

He answered, “I heard you in the garden; but

I was afraid, because I was naked, so I hid.”

Then God asked: Who told you that you were

naked? Have you eaten from the tree of which I had forbidden you to eat? (Genesis 3:8-11)

|

| God Accusing Adam and Eve Italian, c. 1286-1300 Torri in Sabina, Santa Maria in Vescovio, Santa Maria in Vescovio |

|

| Francesco and Jacopo Bassano, Adam Discovered By God Italian, c. 1570 Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado |

|

| Jan van der Straet, God Discovering the Fall Belgian, c. 1585-1587 Florence, Palazzo Della Gherardesca, Chapel |

|

| Charles Joseph Natoire, The Rebuke of Adam and Eve French, 1740 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

|

| Ernst Deger, Adam and Eve Hide from God German, c. 1849-1859 Stolzenfels, Schloss Stolzenfels, Chapel |

Then the Blame Game begins (and it hasn't ended since).

The man replied, “The woman whom you put here with me—she gave me fruit from the tree, so I ate it.”

The LORD God then asked the woman: What is

this you have done? The woman answered, “The snake tricked me, so I ate it.” (Genesis 3:12-13)

The fingers are pointed as if to say, "It's not my fault! She or he made me do it/led me astray/enticed me. Don't look at me, I'm just a poor victim."

The fingers are pointed as if to say, "It's not my fault! She or he made me do it/led me astray/enticed me. Don't look at me, I'm just a poor victim."

|

| God Questions Adam and Eve German, 1015 Hildesheim, Church of Saint Mary |

|

| Pieter Coecke van Aelst, Adam Accuses Eve Flemish, after 1540 Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum |

|

| Pablo de Cespedes, God Questions Adam and Eve Spanish, c. 1577 Rome, Santissima Trinita dei Monti, Cappella Bonfili |

|

| Domenichino, God Questions Adam and Eve Italian, 1626 Washington, National Gallery of Art |

|

| Francisco Bayeu y Subias, God Questions Adam and Eve Spanish, 1771 Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado |

All through the history of Western art artists have been drawn to depict this story. In just about every era and place there are images of Adam and Eve, our first parents, whose inclinations toward curiosity, willfulness and disobedience we have all inherited. Their sin is also ours, by descent, Original Sin. It is our tendency to listen to the whispers of the ‘serpent’ telling us that it’s OK to do this or that because we want to. After all it will make us ‘like gods’ for the moment (and usually resulting in the immediate realization that the fruit can be very bitter indeed).

Because this

strikes such a chord of response throughout the ages the image of the decisive

moment is one of the most common in all of art history.

In Sculpture and Architectural Decoration

Starting

with images from the early years of Christian church building, through all the

eras that followed, the image of the naked couple has been constant in our architectural decoration and sculpture, as well as in our painting.

|

| Fragment of Floor Mosaic from an Early Byzantine Church Northern Syrian, late 5th-early 6th Century Cleveland, Museum of Art |

|

| The Fall of Man German, 1015 Hildesheim, Church of Saint Mary |

|

| Gislebertus, Eve Takes the Fruit French, c. 1130 Autun, Musée Rolin |

|

| The Fall of Man Italian, c. 1174-1189 Monreale, Church of Santa Maria la Nuova |

|

| Stories from Genesis Italian, c. 1180-1190 Monreale, Cathedral |

|

| Cameo of Carnelian, Diamond Gold and Silver, The Fall of Man Italian, c. 1350 St. Petersburg, State Hermitage Museum |

|

| Giovanni Bon, The Fall of Man Italian, c. 1400-1410 Venice, Palazzo Ducale |

|

| Jacopo della Quercia, The Fall of Man Italian, c. 1425-1428 Bologna, Church of San Petronio |

|

| Tillman Riemenschneider, Adam and Eve German, c. 1491-1493 Würzburg, Mainfränkisches Museum |

|

| Meester IP, Model for a jewel South German, 1530 Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum |

|

| Johann Brabender, The Fall of Man German, c. 1550 Muenster, Museum für Kunst und Kultur |

|

| The Fall of Man South German or Austrian, c. 1600-1650 Washington, National Gallery of Art |

|

| Nicolo Roccaatagliata, Adam and Eve Italian, c. 1625-1630 Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum |

|

| Franz Erler, The Fall of Man Austrian, c, 1879 Vienna, Church of the Divine Savior |

|

| Gottfried Schadow, Adam and Eve German, c. 1906-1907 Berlin, Nationalgalerie der Staatliche Museen zu Berlin |

|

| Auguste Rodin, Adam French, c. 1880-1881 Cast 1910 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

|

| Auguste Rodin, Eve French, c. 1880-1881 Cast 1910 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

In Painting

Sometimes Adam and Eve have been shown simply standing, sometimes with the snake, sometimes

without. In some images they appear in the sense of a symbolic reference. We are just given the key to the narrative,

we do not see the event taking place. We

are the ones who supply the narrative when we see the image.

|

| Adam and Eve Italian, c. 1286-1300 Torri in Sabina, Church of Santa Maria in Vescovio |

|

| Masolino da Panicale, Adam and Eve Italian, c. 1426-1427 Florence, Church of Santa Maria del Carmine, Brancacci Chapel |

|

| Paolo Uccello, Adam and Eve Italian, c. 1432-1436 Florence, Church of Santa Maria Novella, Green Cloister |

|

| The Rambures Master, Three Temptations (Jacob Tempting Esau, The Devil Tempting Christ in the Wilderness and the Temptation of Adam and Eve From a Biblia pauperum French (Hesdin or Amiens), c. 1470 The Hague, Meermano Museum MS MMW 10 A15, fol. 25v |

|

| Jean Colombe and Workshop, Adam and Eve From the Hours of Anne of France French (Bourges), 1473 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M 677, fol. 48v |

|

| Hendrick Goltzius after Bartholomeus Spranger, Adam and Eve Dutch, 1585 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

But, mostly, and from early on, the vast majority of images show the story, the event, the crucial action that determined so much. For with the eating of the fruit, which is usually shown as an apple, the first parents chose to disobey the God who had given them everything and set for us the example and the inclination to do the same thing. So, in these images we will see the apple (sometimes shown as a pear or as a pomegranate as well) in the hand of one or other or both. One, usually but not always shown as Eve, will be the most active figure. She reaches for the apple in the tree, or hands it to her spouse with more or less coyness.

|

| The Fall of Man From the Moutier-Grandval Bible French, c. 840 London, British Library MS 10546

This page in a Carolingian Bible tells the entire story of Adam and Eve, from the Creation of Adam to their life after their expulsion from Eden. |

|

| The Fall of Man From the St. Alban's Psalter (Psalter of Christina of Markyate) English (Abbey of St. Alban's), First half 12th Century Hildesheim Dombibliothek MS St. God. 1, fol. 17 |

|

| The Fall of Man From a Picture Bible French (St. Omer), c. 1190-1200 The Hague, Koninklijk Bibliotheek MS KB 76 F 5, fol. 2v |

|

| The Fall of Man From a Gospel Book Austrian (Seitenstetten), c. 1225-1275 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M 808, fol. 196r

Here the two are already wearing fig leaves, even though they have just begun to eat, and seemingly oblivious to God, who watches from above.

|

|

| God Warning Adam and Eve and The Fall of Man From the Psalter of St. Louis and Blanche of Castille French, c. 1225 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Arsenal 1186, fol. 11v |

|

| The Fall of Man From a Compendium historiae in genealogia Christi English (Ramsey Abbey), c. 1250-1299 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M628, fol. 2r |

Illustrations of Biblical stories were not limited to Christian books. Many Hebrew books contained illustrations as well.

|

| The Cholet Group, The Fall of Man From a Northern French Hebrew Biblical Miscellany French (Paris), c. 1283-1285 London, British Library MS Additional 11639, fol. 520v |

|

The Fall of Man

From a Bible historiale by Guiard des Moulins

French (Paris), c. 1400-1425

Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France

MS Francais 160, fol. 9 |

|

The Fall of Man

From a Bible historiale by Guiard des Moulins

French (Paris), c/ 1350-1375

Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France

MS Francais 161, fol. 9v

|

|

| Bertram of Minden, The Fall of Man German, 1379 Hamburg, Hauptkirche Sankt Petri |

|

| The Fall of Man From a Bible historiale by Guiard des Moulins French (Paris), Beginning of 15th Century Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 9, fol. 9 |

|

| Jacob Tempting Esau, Satan Tempting Christ, Temptation of Adam and Eve Page from a Biblia pauperum German, c. 1450-1465 Cleveland, Museum of Art |

|

| Hugo van der Goes, The Fall of Man Belgian, c. 1479 Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum

In this charming painting by van der Goes, the serpent is shown as a creature with four legs, something that is implied in the Scripture, but frequently overlooked by artists.

|

|

| The Fall of Man from a Book of Hours French (Paris), c. 1495-1505 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M 197, fol.17v |

|

| Hans Memling, The Fall of Man German, c. 1485 Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum |

|

| Anonymous, The Fall of Man Dutch, 16th Century Dresden, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden. |

|

| Albrecht Dürer, The Fall of Man (drawing) German, 1504 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library |

|

| Albrecht Dürer, The Fall of Man (engraving) German, 1504 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

|

| Raphael, The Fall of Man Italian, c. 1509-1511 Vatican, Apostolic Palace, Stanza della Segnatura ceiling |

|

| Michelangelo, The Fall of Man and the Expulsion from Eden Italian, c. 1508-1512 Vatican, Sistine Chapel |

The almost simultaneous visions of Dürer and Raphael and Michelangelo would prove to be normative for the succeeding centuries, right up to the end of the nineteenth century. From Dürer, some artists will take the side by side stance of the figures, from Raphael they will take the gesture of reaching up to the tree and from Michelangelo they will take the spiraling posture.

|

| Hans Baldung Grien, The Fall of Man German, c. 1510-1520 Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi |

|

| Jan Gossaert, The Fall of Man Flemish, c. 1510 Madrid, Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza |

|

| Lucas Cranach the Elder, The Fall of Man German, 1526 London, Courtauld Gallery |

|

| Anonymous, The Fall of Man Flemish, c. 1530 Berlin, Jagdschloss Grünewald |

|

| Lucas Cranach the Elder, The Fall of Man German, c. 1537 Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum |

|

| Lucas Cranach Younger, The Fall of Man German, 1549 Houston, Museum of Fine Arts |

|

| Michiel Coxie, The Fall of Man Belgian, c. 1540 Cologne, Wallraf-Richartz-Museum & Fondation Corboud |

|

| Titian, The Fall of Man Italian, c. 1550 Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado |

|

| Tintoretto, The Fall of Man Italian, c. 1551-1552 Venice, Gallerie dell'Accademia |

|

| Michiel Coxie, The Fall of Man Belgian, c. 1570 Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum |

|

| Tintoretto, The Fall of Man Italian, c. 1577-1578 Venice, Scuola Grande di San Rocco |

All of these

elements combine in the early Baroque period into a gesture of offering, frequently standing, which

may come from either Adam or Eve, and which adds a hint of sensuality that was

not present in earlier periods.

|

| +Santi di Tito, The Fall of Man Italian, c. 1580-1603 Florence, Museo di Casa Martelli |

|

| Jan van der Straet, The Fall of Man Belgian, c. 1585-1587 Florence, Palazzo Della Gherardesca, Chapel |

|

| Hendrick Goltzius, The Fall of Man Dutch, c. 1600 Hamburg, Hamburger Kunsthalle |

|

| Studio of Frans Francken II, The Fall of Man The Sudbury Cabinet Belgian, c. 1600-1642 Derbyshire (UK), Sudbury Hall |

|

| Peter Paul Rubens with Jan Breughel the Elder, The Fall of Man (Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden) Flemish, c. 1615 The Hague, Mauritshaus Museum |

|

| Hendrick Goltius, The Fall of Man Flemish, 1616 Washington, National Gallery of Art |

|

| Jacob Savery II, The Fall of Man Dutch, c. 1630 Private Collection |

|

| Izaac van Oosten, The Fall of Man Dutch, c. 1640-1650 Private Collection |

|

| Jacob Jordaens, The Fall of Man Belgian, c. 1640 Budapest, Szépmûvészeti Múzeum |

|

| Jacopo Amigoni, The Fall of Man Italian, 1728 Ottobeuren, Ottobeuren Abbey, Chapel of St. Benedict |

|

| James Barry, The Fall of Man Irish, c. 1767-1770 Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland |

|

| Peter Wenzel, The Fall of Man German, c. 1820-1830 Vatican, Pinacoteca |

|

| Edward Burne-Jones, The Fall of Man Design for Stained Glass Window English, c. 1870-1890 London, Victoria and Albert Museum |

|

| Hans Thoma, The Fall of Man German, 1897 St. Petersburg, State Hermitage Museum |

|

| Othon Friesz, The Fall of Man French, c. 1910 St. Petersburg, State Hermitage Museum |

|

| Max Beckmann, The Fall of Man German, 1917 Berlin, Nationalgalerie der Staatliche Museen zu Berlin |

Occasionally,

we are shown the moment when they recognize their changed condition, when they

recognize that they are naked, no longer the happy, innocent animals they

were. They are indeed now “like gods who know what is good and what is evil”. They suddenly are us, with the sickening awareness

of what our actions have really done.

|

| Jean Bondol, Adam Realizes What He Has Done From a Bible historiale completee by Guiard des Moulilns French (Paris), c. 1371-1372 The Hague, Museum Meermano MS MMW 10 B 23, fol. 10r |

|

| Henry Keller, The Fall of Man American, c. 1909-1912 Cleveland, Museum of Art |

Their example has been followed millions of times as humans have grasped the tempting fruit, whatever that fruit may represent, be it money or glory or pride or sex or power over others, whatever it is that tempts us with the promise that “you will be like gods”.

Each year

Lent offers us a chance to assess our grasping over the last year or over our

whole lives, a chance to repent the choices that seemed so tempting and proved

so bitter and a chance to repair some of the damage we have done along the

way.

©

M. Duffy, 2017. Selected images have been updated and new images added 2024 and 2025.

+Indicates updated image

*Indicates new image

Excerpts

from the Lectionary for Mass for Use in the Dioceses of

the United States of America, second typical edition © 2001,

1998, 1997, 1986, 1970 Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, Inc., Washington,

DC. Used with permission. All rights reserved. No portion of this text may be

reproduced by any means without permission in writing from the copyright owner.

,%201400-1425_BNF_Francais%20160,%20fol.%208v_2.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment