|

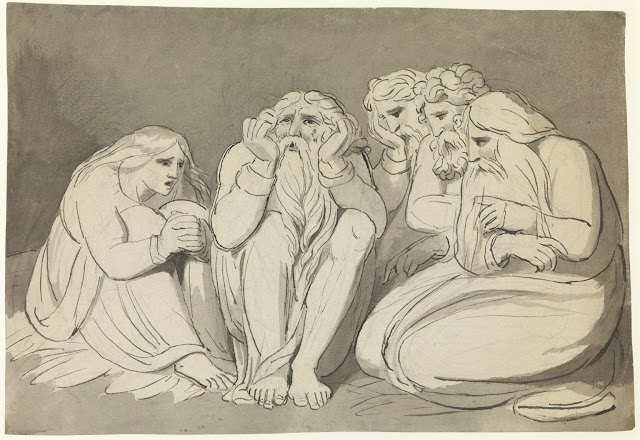

| William Blake, Job's Evil Dreams Plate 11, Illustrations to the Book of Job English, Watercolor, 1805-1810 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library |

Job spoke, saying:

Is not man's life on earth a drudgery?

Are not his days those of hirelings?

He is a slave who longs for the shade,

a hireling who waits for his wages.

So I have been assigned months of misery,

and troubled nights have been allotted to me.

If in bed I say, "When shall I arise?"

then the night drags on;

I am filled with restlessness until the dawn.

My days are swifter than a weaver's shuttle;

they come to an end without hope.

Remember that my life is like the wind;

I shall not see happiness again.

Job 7:1-4, 6-7

(First Reading, Fifth Sunday of Ordinary Time, Year B)

The first reading from the Mass for the Fifth Sunday in Ordinary Time, Year B should remind us that illness, job stress and nighttime worry is nothing new. And don’t our days frequently feel like this?

This passage also brings to mind an image, taken from some verses further on in the same chapter of Job (Job 7:13-15), from William Blake’s Illustrations to the Book of Job, issued first as a series of watercolors for his patron, Thomas Butts. They were later engraved and published in 1826. Called "Job's Evil Dreams" it well illustrates the sometimes terrifying world of the nightmare. Job lies on his bed, surrounded by flames and tormented by Satan (identified by his cloven foot) and other demons. They press upon him from above and reach up to bind him in chains from below. Truly, they are visions that terrify.

So that I should prefer choking and death rather than my pains.

Job 7:13-15

However, Blake’s image and our own reactions are not the only responses possible to Job’s situation. Indeed, they come very late in the history of Christian interpretations of the Book of Job.

The first reading from the Mass for the Fifth Sunday in Ordinary Time, Year B should remind us that illness, job stress and nighttime worry is nothing new. And don’t our days frequently feel like this?

This passage also brings to mind an image, taken from some verses further on in the same chapter of Job (Job 7:13-15), from William Blake’s Illustrations to the Book of Job, issued first as a series of watercolors for his patron, Thomas Butts. They were later engraved and published in 1826. Called "Job's Evil Dreams" it well illustrates the sometimes terrifying world of the nightmare. Job lies on his bed, surrounded by flames and tormented by Satan (identified by his cloven foot) and other demons. They press upon him from above and reach up to bind him in chains from below. Truly, they are visions that terrify.

When I say, "My bed shall comfort me, my couch shall ease my complaint,"

Then you affright me with dreams and with visions terrify me, So that I should prefer choking and death rather than my pains.

Job 7:13-15

William Blake, Job's Evil Dreams

from Illustrations of the Book of Job

English, 1826

New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art

|

However, Blake’s image and our own reactions are not the only responses possible to Job’s situation. Indeed, they come very late in the history of Christian interpretations of the Book of Job.

,%20Mid-14th%20Century_Paris,%20BNf_MS%20Francais%20152,%20fo.%20234r_2.jpg) |

| The Story of Job From a Bible historiale by Gerard des Moulins French (St. Omer), mid-14th century Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 152, fol. 234 |

The Old or Jewish Testament was embraced by Christians from the very beginning. St. Paul’s letters are filled with references from the Jewish Scriptures, and the slightly later canonical Gospels make constant references to them, in quotes used by Jesus, in subtle allusions to situations and events that reflect back to the Scriptures.

Some of the earliest Christian art includes an illustration of Job's sufferings. For example, it appears on the Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus, dating to 359, only a few decades after the legalization of Christianity by the Roman Emperor Constantine (in 315).

|

| Job on the Dunghill Detail from the Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus Roman, c. 359 Vatican City, Vatican Museums, Museo Storico del Tesoro della Basilica di San Pietro |

Surviving early manuscripts from what is now Iraq and from Greece also include scenes from the Book of Job.

,%20c.%20500-700_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Syriaque%20341,%20fol.%2016r.jpg) |

| Job, His Wife and Friends From a Bible Syriac (Iraq), c. 500-700 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Syriaque 341, fol. 16r |

|

| The Affliction of Job From a Bible Greek, c. 8th-9th Century Vatican City, Biblioteca apostolica vaticana MS Vat. gr. 749, Part 1, fol. 25r |

|

| Job Arguing with His Friends From a Bible Greek, c. 8th-9th Century Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana MS Vat.gr.749, Part 2, fol. 126r |

In these early works and in the subsequent medieval and later periods artists had what might be called an external vision of Job’s trials. Images detailed the destruction of his possessions and his family, his torments (often personifying Satan as the agent of them), his conversations with his three “friends”, Eliphaz, Bildad and Zophar. The "friends" attempt to explain the misfortunes of Job as a punishment from God for having sinned in some way, while Job denies their assertions and maintains his own rightousness, blaming God for his sufferings. He points out that frequently it is those who fear and obey God who are the ones who suffer, while the evil seem to be rewarded with the good things of the world. This exploration of the inequality of suffering has always been a valuable one for believers to consider, since the same conditions apply today just as they applied when Job was written.

|

| Eliphaz Addressing Job From a Bible Greek, 9th Century Patmos, Monastery of Saint John the Theologian MS Codex 171, fol. 75 |

|

| Job and His Friends From a Bible Greek, 905 Venice, Biblioteca Marciana MS Gr. 538, fol. 27r |

|

| Job Marble Capital From Notre-Dame des Doms French, c. 1150 Avignon, Musée du Petit Palais |

,%20c.%201200-1250_Paris,%20BNf_MS%20Latin%202232,%20fol.%2014r.jpg) |

| Job and His Friends From a Moralia in Job by Saint Gregory the Great Italian (Perugia), c. 1200-1250 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 2232, fol. 14r |

,%20c.%201250_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Latin%20796,%20fol.%20200v.jpg) |

| Job, His Wife and Friends From a Breviary French (Montieramey), c. 1250 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 796, fol. 200v |

,%20c.%201350_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Francais%20161,%20fol.%20226v.jpg) |

| Master of the Bréviary of Senlis, Job and His Friends From a Bible historiale by Giuard des Moulins French (Paris), c. 1350 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 161, fol. 226v |

,%20c.%201400_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Francais%203,%20fol.%20255r_2.jpg) |

| Job Admonished By His Friends and His Wife From a Bible historiale by Guiard des Moulins France, Paris, Early 15th century Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 3, fol. 255r |

|

| Jean Fouquet, Job on the Dunghill and His Friends From the Book of Hours of Etienne Chevalier French, c. 1452-1460 Chantilly, Musée Condé |

,%20c.%201490=1500_The%20Hague,%20KB_MS%20KB%2076%20F%2014,%20fol.%2078r_copy.jpg) |

| Job on the Dunghill with His Friends From a Book of Hours French (Paris), c. 1490-1500 The Hague, Koninklijk Bibliotheek MS KB 76 F 14, fol. 78r |

,%20c.%201503-1508_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Latin%209474,%20fol.%20119v.jpeg) |

| Jean Bourdichon, Job and His Friends From a Book of Hours French (Tours), c. 1503-1508 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 9474, fol. 119v |

|

| William Blake, Job Rebuked by His Friends English, c. 1805-1810 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library and Museum |

An interesting feature of the images I located in my search is that, in the main, they come not from Latin language texts (i.e., from illustrations of the Vulgate, works of the Fathers [for instance the Moralia in Job of St. Gregory the Great] or from Books of Hours), but from books written in the vernacular languages of Europe or popular picture books such as illustrated Bibles or the Speculum humanae salvationis, that is from books available to and read by literate lay persons.

|

| William Blake, Satan Smiting Job with Sore Boils English c. 1805-1810 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library and Museum |

A favorite image was of Job being nagged by his wife. This last is from the same strain of “comic relief” that saw other Biblical nagging wives feature in medieval mystery and morality plays. Mrs. Noah, Mrs. Lot and Mrs. Job were popular characters, their assaults on their husbands moments of fun for the audience.

,%20c.%201245-1255_New%20York,%20Pierpont%20Morgan%20Library_MS%20G%2031,%20fol.%20156r.jpg) |

| The Christina Workshop, Job and His Wife From a Bible French (Paris), c. 1245-1255 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS G 31, fol. 156r |

,%20c.%201320-1340_The%20Hague,%20KB_MS%20KB%2071%20A%2023,%20fol.204v.jpg) |

| Master of Fauvel, Job with His Wife and Friends From a Bible historiale completée by Guiard des Moulins French (Paris), c. 1320-1340 The Hague, Koninklijk Bibliotheek MS KB 71 A 23, fol.204v |

,%20c.%201465-1475_New%20York,%20Pierpont_MS%20M%20285,%20fol.%20261v.jpg) |

| Job Visited by His Wife and Musicians From a Book of Hours Flemish (Bruges), c. 1465-1475 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M 285, fol. 261v |

|

| Albrecht Durer, Job and His Wife German, c. 1504 Frankfurt, Stadelsches Kunstinstitut |

,%20c.%201547-1559_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Latin%201429,%20fol.%2073v.jpeg) |

| Master of the Getty Epistles, Job with His Wife and Friends From a Book of Hours French (Paris), c. 1547-1559 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 1429, fol. 73v |

|

| Attributed to David Ryckaert III, Job Tormented by His Wife Flemish, c. 1630-1331 Paris, Musée du Louvre |

Sometimes, however, Mrs. Job is not so much a stock figure of the nagging wife, she is actually a willing participant in the torments being heaped upon Job. She is often shown as an onlooker, or even a participant, in the work of Satan.

,%20c.%201370-1380_Paris,%20BNf_MS%20Latin%20511,%20fol.%2021r.jpg) |

| Job Tormented by Satan and His Wife From a Speculum humanae salvationis French (Alsace), c. 1370-1380 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 511, fol. 21r |

|

| Job Tormented By Satan, By His Wife and By Boils From Speculum humanae salvationis France, Mid-15th century Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 188, fol. 25 |

,%20c.%201467_The%20Hague,%20KB_MS%20KB%2078%20D%2039,%20fol.%20308r.jpg) |

| Master of the Feathery Clouds, Job on the Dunghill Tormented by Satan, His Wife and His Friends From a History Bible Dutch (Utrecht), c. 1467 The Hague, Koninklijk Bibliotheek MS KB 78 D 39, fol. 308r |

,%20c.%201485_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Francais%206275,%20fol.%2022r.jpg) |

| Master of Edward IV, Job Tormented From a Speculum humanae salvationis Flemish (Bruges), c. 1485 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 6275, fol. 22r |

|

| After a lost painting by Peter Paul Rubens, Job Tormented by Demons and Mocked by His Wife Flemish, 17th Century Paris, Musée du Louvre |

For these time periods Job was the symbol of patience, of trials patiently endured. He became the model for Everyman.

,%20c.%201400_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Francais%209,%20fol.%20244t.jpg) |

| Job as a Leper Seated on the Dunghill From a Bible historiale by Guiard des Moulins French (Paris), c. 1400 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 9, fol. 244r |

|

| Jabob Jordaens, Job Flemish, c. 1620 Detroit, Institute of Arts |

It was only later, beginning in the last decades of the eighteenth century, when the artists of the Romantic period with their emphasis on the interior emotions and the self, that such works as Blake’s could have appeared. Although the words of the Biblical text were always there and always available for illustration, they were only looked at when such emotions became attractive to artists and to the public.

|

| William Blake, Job, His Wife and His Friends English, c. 1785 London, Tate Gallery |

|

| William Blake, Job's Despair English, c. 1805-1810 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library and Museum |

,%20Musee%20Bonnat.jpg) |

| Leon Joseph Bonnat, Job French, 1880 Bayonne (FR), Musee Bonnat |

|

| Job with His Wife and Friends American, 1882 Boston, Trinity Church |

|

| Felix Desruelles, Job French, 1896 Valenciennes, Musée des Beaux-Arts |

|

| James Tissot, Job and His Friends From the Old Testament Series French, c. 1896-1902 New York, The Jewish Museum |

|

| James Tissot, Job Lying on the Heap of Refuse French, c. 1896-1902 New York, The Jewish Museum |

© M. Duffy, Originally published 2012, revised with additional material 2024.

,%20c.%201395-1400_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Francais%20159,%20fol.225r.jpg)