2.jpg) |

| Luca Signorelli, The Scourging of Christ Italian, c. 1480 Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera |

"Then Pilate took Jesus and had him scourged."

Gospel for Good Friday, the Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ According to John

(John 19:1)

The Gospel of John is the only one of the Four Gospels that actually says that Pilate had Jesus scourged. The three Synoptic Gospels imply that something like this happened, either at the hands of the Romans under Pontius Pilate or at the hands of the Jewish Temple guards, who first arrested Him. They make references to rough treatment or say that Pilate said that he would have Jesus flogged. Nevertheless, Christian tradition affirms that Jesus suffered the horrific torture of scourging.

We now know from archaeological evidence that much of what tradition says is actually true to the period. We have evidence that includes the skeleton of a crucified man who had been nailed to a cross through the feet, just like Jesus was (see discussion here), and we have plenty of evidence for the terrible whip, the flagrum (plural: flagra) used by the Roman army.

These vicious implements, multiple strand whips to which hard pieces of metal or other materials were added, were intended to inflict as much damage as possible, ripping skin at times. The name flagrum is related to the verb “to flay”, which means to remove the skin from. We know that they existed and that they were used for discipline and for punishment.

|

| Roman Flagrum |

|

| Master of the Registrum Gregorii, The Scourging at the Pillar From the Codex Egberti German, c. 980 Trier, Stadtbibliothek MS Cod. 24 |

|

| The Scourging at the Pillar Miniatures of the Life of Christ French (probably Corbie), c. 1175 New York, Morgan Library MS M 44, fol. 8v |

|

| The Scourging at the Pillar French, c. 1200-1220 London, Victoria and Albert Museum |

|

| The Scourging at the Pillar From a Psalter English, c. 1200 Oxford, University of Oxford, Bodleian-Library MS Gough Liturg 2, fol. 27r |

A Static Image

The earliest images of the Scourging at the Pillar seem more a pictogram of an event, than a true representation of someone being scourged.

Indeed, in the Gothic period the scene almost resembles a courtly dance rather than a true scene of torture. And this is the image that persists for over 200 years.

,%20c.%201200-1225_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20NAL%201392,%20fol.%2010v.jpg) |

| The Scourging at the Pillar From a Psalter French (Paris), c. 1200-1225 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS NAL 1392, fol. 10v |

|

| The Scourging at the Pillar From the Psalter of St. Louis and Blanche of Castille France (Paris), c. 1225 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS-1186 reserve, fol. 23v |

,%20c.%201250_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Latin%2010434,%20fol.%2015v.jpg) |

| The Scourging at the Pillar From a Psalter known as the Psalter of Blanche of Castille French (Paris), c. 1250 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 10434, fol. 15v |

,%20c.%201250-1300_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Smith-Lesou%C3%ABf%2020,%20fol.%2073r.jpg) |

| The Scourging at the Pillar From a Psalter French (Saint-Omer), c. 1250-1300 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Smith-Lesouëf 20, fol. 73r |

,%20c.%201275-1300_Paris,%20Bibliotheque%20nationale%20de%20France_MS%20Nouvelle%20acquisition%20francaise%2016251,%20fol.%2036r.jpeg) |

| The Scourging at the Pillar From the Livre d’images de Madame Marie Flemish (Hainaut), c. 1275-1300 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS NAF 16251, fol. 36r |

|

| Cimabue, The Scourging at the Pillar Italian, c. 1280 New York, The Frick Collection |

,%20c.%201300_Oxford,%20Bodleian%20Library_MS%20Gough%20Liturg-8,%20fol.%2049r.jpg) |

| The Scourging at the Pillar From a Psalter English (East Anglia), c. 1300 Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Gough Liturg-8, fol. 49r |

|

| Duccio, Pilate Orders Jesus to be Scourged Italian, 1308-1311 Siena, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo |

|

| Pietro Lorenzetti, Pilate Orders the Scourging of Jesus Italian, c. 1320 Assisi, Basilica of San Francesco, Lower Church |

,%20c.%201325-1350_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Francais%20185,%20fol.%2010v.jpg) |

The Scourging at the Pillar and Jesus Carrying the Cross From a Vie de saints French (Paris), c. 1325-1350 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 185, fol. 10v |

|

| Ugolino di Nerio, The Scourging at the Pillar Italian, c. 1325 Berlin, Gemäldegalerie der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin |

|

| Master of the Poldi Pezzoli Diptych, Pilate Orders the Scourging of Jesus Italian, c. 1335-1340 Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera |

,%20c.%201350_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Francais%209561,%20fol.%20171v+2.jpeg) |

| Pilate Orders the Scourging of Jesus From a Vies de la Vierge et du Christ Italian (Naples), c. 1350 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 9561, fol. 171v |

|

| The Scourging at the Pillar From the Salisbury Psalter English, c. 1350-1375 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 765, fol. 12r |

|

| Luca di Tomme, Pilate Orders the Scourging of Jesus Italian, c. 1365 Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum |

,%20c.%201371-1372_The%20Hague,%20Meermano%20Museum_%20MS%20RMMW%2010%20B%2023,%20fol.%20522r.jpg) |

| Jean Bondol and Others, The Scourging at the Pillar From a Grande Bible Historiale Completée by Guiard des Moulins French (Paris), c. 1371-1372 The Hague, Meermano Museum_ MS RMMW 10 B 23, fol. 522r |

|

| The Scourging at the Pillar English, Late 14th Century London, Victoria and Albert Museum |

,%20c.%201380_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Latin%2014033,%20fol.%2047r.jpeg) |

| The Scourging at the Pillar From a Book of Hours, known as the Hours of Isabeau of Bavaria, Queen of France French (Metz), c. 1380 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 14033, fol. 47r |

,%20c.%201385-1390_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Latin%2018014,%20fol.%2093v.jpg) |

| Jean le Noir, The Scourging at the Pillar From the Petites Heures of Jean de Berry French (Bourges), c. 1385-1390 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 18014, fol. 93v |

,%20c.%201385-1390_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Latin%20757m%20fol.%20254v.jpg) |

| Giovanni di Benedetto & Workshop, The Scourging at the Pillar From a Missal Italian (Milan), c. 1385-1390 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 757m fol. 254v |

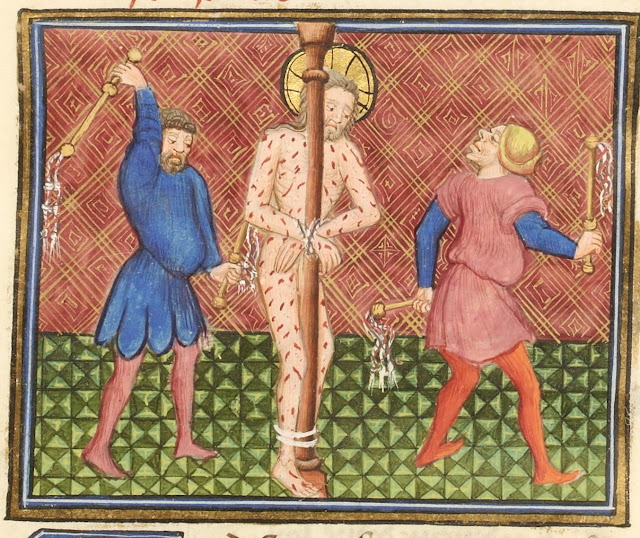

Increasing Violence

However, starting around 1450, the levels of violence and cruelty depicted gradually increased, even though the composition of the figures remained basically unchanged.

,%201463_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Francais%2050,%20fol.%20230r%20(2).jpg) |

| Master Francois and Workshop, The Scourging at the Pillar From Speculum historiale by Vincent of Beauvais French (Paris), 1463 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 50, fol. 230r |

,%20c.%201475_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Francais%20179,%20fol.%2093r.jpg) |

| Jean Colombe, The Scourging at the Pillar From a Vita Jesu Christi by Ludolph of Saxony French (Bourges), c. 1475 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 179, fol. 93r |

|

| The Scourging at the Pillar German, c. 1480-1490 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Cloisters Collection |

,%20c.%201485_Paris,%20BNF_Ms%20Francais%206275,%20fol.%2021v.jpg) |

| Master of Edward IV, The Scourging at the Pillar From a Speculum humanae salvationis Flemish (Bruges), c. 1485 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France Ms Francais 6275, fol. 21v |

,%20End%20of%20the%2015th%20Century_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Espagnol%20544,%20fol.%2028v.jpeg) |

| The Scourging at the Pillar, on the Back From a Speculum animae Spanish (Catalan), End of the 15th Century Paris, Bibliotheque nataionale de France MS Espagnol 544, fol. 28v |

,%20End%20of%20the%2015th%20Century_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Espagnol%20544,%20fol.%2029r.jpeg) |

| The Scourging at the Pillar, on the Front From a Speculum animae Spanish (Catalan), End of the 15th Century Paris, Bibliotheque nataionale de France MS Espagnol 544, fol. 29r |

|

| Michael Pacher, Fragment of a Scourging at the Pillar German, c. 1497-1498 Vienna, Belvedere Museum |

|

| Anton Woensam, The Scourging at the Pillar German, 16th Century Chambery, Musée des Beaux-Arts |

,%20c.%20150-1510_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20Latin%20923,%20fol.%2014r.jpeg) |

| Workshop of Jean Pichore, The Scourging at the Pillar From a Book of Hours French (Paris), c. 150-1510 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 923, fol. 14r |

|

| Luca Signorelli, The Scourging at the Pillar Italian, 1502 Cortona, Museo Diocesano |

|

| Bacchiacca, The Scourging at the Pillar Italian, c. 1512-1515 Washington, National Gallery of Art |

| |

| Sebastiano del Piombo, The Scourging at the Pillar Italian, c. 1516-1524 Rome, Church of San Pietro in Montorio |

|

| Albrecht Altdorfer, The Scourging at the Pillar German, 1518 Sankt Florian bei Linz, Augustinian Abbey |

|

| Joerg Ratgeb, The Scourging at the Pillar German, c. 1518-1519 Stuttgart, Staatsgalerie Although the central image is the Scourging, this picture includes multiple scenes from the Passion |

|

| Jean Penicaud the Elder, The Scourging at the Pillar French, c. 1525 London, Victoria and Albert Museum |

|

| Lucas Cranach the Elder, The Scourging at the Pillar German, 1538 Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum |

,%20c.%201540-1560_Paris,%20Musee%20du%20Louvre,%20D%C3%A9partement%20des%20Sculptures%20du%20Moyen%20Age,%20de%20la%20Renaissance%20et%20des%20temps%20modernes.JPG) |

| The Scourging at the Pillar French (Saint Denis), c. 1540-1560 Paris, Musée du Louvre, Département des Sculptures du Moyen Age, de la Renaissance et des temps modernes |

The Violence Increases

Following on from the work of the Venetian painter, Titian, the violence reached a crescendo with the work of Caravaggio (another north Italian) and his followers at the beginning of the 17th century. The tormentors in these paintings really get into their work.

|

| Pier Francesco Mazzucchelli, The Scourging of Jesus Italian, c. 1615-1620 Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado |

|

| David Teniers, The Scourging at the Pillar Flemish, Middle of the 17th Century Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado |

|

| Guercino, The Scourging at the Pillar Italian, 1657 Rome, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Barbarini-Cornsini Galleries |

Devotional Images

There was another way of depicting the Scourging, found in the realm of devotional iconography. These images begin to appear in the North, where devotional images often originate. They present the figure of the bleeding, wounded Jesus to the viewer for prayer and adoration.

,%20c.%201420-1440_Washington,%20Library%20of%20Congress_MS%20213,%20fol.%2044v.jpg) |

| Follower of the master of the Gold Scrolls, Angels Adore the Wounded Christ From a Book of Hours Flemish (Bruges), c. 1420-1440 Washington, Library of Congress MS 213, fol. 44v |

,%20c.%201485_Paris,%20BNF_Ms%20Francais%206275,%20fol.%2045v.jpg) |

| Master of Edward IV, A Donor Prays Before a Vision of the Scourging at the Pillar From a Speculum humanae salvationis Flemish (Bruges), c. 1485 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 6275, fol. 45v |

|

| Hans Memling, Christ at the Column Flemish, c. 1485-1490 Barcelona, Coleccion Mateu |

|

| Christ at the Column Spanish, Early 16th Century Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado |

Artists also imagined the exhausted, wounded Christ painfully retrieving his garments or simply exhausted after the scourging. Frequently the Christ in this kind of image is shown as a focus for prayerful, sympathetic contemplation by both angels and humans. This type of image became popular in the seventeenth century, especially in Spain.

|

| Diego Velazquez, Christ Contemplated by the Christian Soul Spanish, c. 1628-1629 London, National Gallery |

|

| Alonso Cano, Christ Recovering His Garments after the Scourging Spanish, c. 1645-1650 Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado |

|

| Bartolome Esteban Murillo, Christ After the Scourging Spanish, After 1665 Boston, Museum of Fine Arts |

|

| Bartolome Esteban Murillo, Christ at the Column with Saint Peter Spanish, c. 1670 Paris, Musée du Louvre |

|

| Anonymous, Christ After the Scourging German, c. 1725-1730 Ettal, Abbey Church of the Assumption, Sacristy |

According to art historian, John F. Mofitt, this unusual series of depictions of the aftermath of the Scourging derives from a number of works of advice on Christian prayer, stretching from the thirteenth-century Meditationies Vitae Christi by the Pseudo-Bonaventure to the sixteenth-century Spiritual Exercises of Saint Ignatius Loyola to the early seventeenth-century Introduction to the Devout Life of Saint Francis de Sales. All of these works proposed contemplation of the sufferings of Christ and the last, in particular, encouraged contemplation of the moments after the end of the Scourging.1

© M.

Duffy, 2013. Additional images added 2023. Images updated and new material added 2024.

1. Moffitt, John F. "The Meaning of 'Christ After the Flagellation' in Siglo de Oro Sevillian Painting", Wallraf-Richartz-Jahrbuch , 1992, Vol. 53 (1992), pp. 139-154.

Excerpts

from the Lectionary for Mass for Use in the Dioceses of

the United States of America, second typical edition © 2001,

1998, 1997, 1986, 1970 Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, Inc., Washington,

DC. Used with permission. All rights reserved. No portion of this text may be

reproduced by any means without permission in writing from the copyright owner.

,%201452_Paris,%20BNF_MS%20NAL%203244,%20fol.%20252r_2.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment