|

Attributed to Jean le Noir, The Mocking of Christ From the Petites heures of Jean de Berry French (Paris), 1375 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 18014, fol. 82r |

The accounts of the Passion all describe the mocking of Christ. He is blindfolded, struck repeatedly, spat upon. A crown of thorns is placed on His head and he is mocked as “King of the Jews”. Later Pilate orders him to be scourged. (Matthew 26:67-69; Mark 14:65; Luke 22:63-65; John 19:1-3).

Most of the images of the Mocking of Christ are narrative in nature, reflecting the Gospel accounts. They portray the scene as they imagine it may have looked. Usually Christ appears, either standing or seated, amidst two or more of his tormentors.

|

| Christ Before Pilate and Christ Mocked From a Psalter German (Bavaria), c. 1236 Munich, Bayerisches Staatsbibliothek MS Clm 11308, fol. 9r |

,%20c.%201285-1290_Paris,%20Bibliotheque%20nationale%20de%20France_MS%20Nouvelle%20acquisition%20francaise%2016251,%20fol.jpg) |

| Master Henri, The Mocking of Christ From the Livre d'images de Madame Marie Flemish (Hainaut), c. 1285-1290 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Nouvelle acquisition francaise 16251, fol. 35v |

|

| The Mocking of Christ From a Speculum historiale by Vincent of Beauvais French, c. 1396 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 312, fol. 308r |

|

The Mocking of Christ From the Salisbury Psalter English, c. 1450-1475 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Latin 765, fol. 10r |

|

The Mocking of Christ From a Prayer Book Dutch, c. 1515-1525 The Hague, Koninklijk Bibliothek MS MMW 10 F 21, fol. 81v |

One is, however, different.

Fra Angelico at the Convent of San Marco

Among the most striking visual meditations on the Passion is a painting at the Convent of San Marco in Florence. It was painted by Fra Angelico in the period 1441-1445, when Angelico was engaged in decorating the cells of his fellow Dominican friars with some of the most remarkable religious images ever painted. 1

In the period between 1438, when the Convent of San Marco in Florence was transferred to the Order of Preachers (Dominicans), and 1445, when the renovations which followed their acquisition of the property were completed, Fra Angelico (real name in religion Fra Giovanni da Fiesole) and his assistants painted a series of frescoes in the corridors and other common spaces and in each of the cells in which the friars lived. The paintings in the cells are perhaps the most individual works of Christian art that have ever been painted. They are, in general, not at all like the depictions of similar scenes by other Quattrocento artists. Rather, they are visions and meditations in paint. The painting located in Cell No. 7 is probably the most unusual of these very unusual images.

In the period between 1438, when the Convent of San Marco in Florence was transferred to the Order of Preachers (Dominicans), and 1445, when the renovations which followed their acquisition of the property were completed, Fra Angelico (real name in religion Fra Giovanni da Fiesole) and his assistants painted a series of frescoes in the corridors and other common spaces and in each of the cells in which the friars lived. The paintings in the cells are perhaps the most individual works of Christian art that have ever been painted. They are, in general, not at all like the depictions of similar scenes by other Quattrocento artists. Rather, they are visions and meditations in paint. The painting located in Cell No. 7 is probably the most unusual of these very unusual images.

|

Fra Angelico and assistants, The Mocking of Christ Italian, c. 1440-1445 Florence, Convent of San Marco, Cell #7 |

In the center of this painting we see the image of Christ, dressed in white, seated before a plain undecorated wall, on which hangs a green cloth of state. His eyes are blindfolded with some thin material that allows us to clearly see the outline of His closed eyes and nose. On His head is a crown of thorns and behind His head is a cruciform halo. In His right hand He holds a segmented staff and in His left hand what appears to be an orb. In other words, He is shown as a king, but a suffering king. The image of the king crowned with thorns is certainly in the tradition of prior images of the Mocking.

|

The Crowning with Thorns From a Pelerinage du Jesus-Christ by Guillaume de Digulleville France (Rennes), c. 1425-1450 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 376, fol. 216 |

However, around His head we can see what are without doubt the most intriguing elements of this picture. Instead of seeing His tormentors standing by, we see only the parts of them that are causing the torment. There are four disembodied hands; two on either side, and all of them are right hands. On the right of the picture, one hand is raised as if preparing to strike Him, while another right hand hits Him with a rod. On the left side one hand reaches up to pull His beard, while another, palm towards us, prepares to slap Him. And, perhaps most exceptional of all, a disembodied head (presumably the owner of the beard pulling hand) launches spittle at Him. Meanwhile, the head’s disembodied left hand mockingly raises his hat.

|

| Fra Angelico, The Mocking of Christ (central image) Italian, c. 1440-1445 Florence, Convent of San Marco |

These elements of the picture are odd enough, but the curious quality of this painting is compounded by the figures in the foreground.

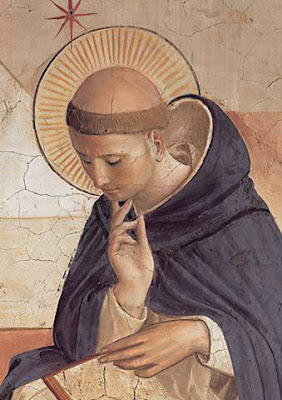

On the left sits, Mary, Jesus’ mother. Her identity is certain because of her continuous presence in many of the San Marco frescoes. Surprisingly, her back is turned to the image of Jesus behind her. On the right, also with his back turned, sits St. Dominic, reading a book. Both of these figures are shown touching their chins with one hand. What can this mean?

First of all, note the separation in level between the central image of Christ and the figures in the foreground. They sit on a shallow step above the ground level. He is raised above them on a higher step, a kind of podium. He is removed from them by this difference of level. Further, the gesture that both are making, that of raising their hands to their chins, is a traditional gesture that indicates intense thought. We still use it today.

Therefore, what we have here is not a visual record of an event, not an illustration of a text, but a visual meditation on the Passion. We are invited by it to enter into the same thoughtful frame of mind as Mary and Dominic. The book in Dominic’s hand indicates that he is in the second level of Lectio Divina, that of meditation. He has read the text and is now pondering it. What we are seeing is his thought. The picture is, quite literally, reading St. Dominic's mind. We are, as it were, "seeing" not with his eyes, but with his mind.

One writer has suggested that all of the frescoes in the cells at San Marco, including this one, were designed to reflect the types of silent prayer that are described in a Dominican prayer manual for the Order’s novices, called De modo orandi.2 The manual was intended as a help in preparing the future friars for their eventual role as preachers. This 13th century handbook was reputed to record the gestures which St. Dominic himself used during silent prayer. The specific gesture in this picture is identified as “recollection”.

The picture itself and the connection to the Dominican prayer manual suggest that this is the ideal work to begin a discussion of painted meditations on the Passion of Jesus Christ.

© M. Duffy, 2012, additional pictures added 2021. New references added 2023.

__________________________________________

1. Scudieri, Magnolia, "The Frescoes by Fra Angelico at San Marco" in Fra Angelico, New York, New Haven and London, The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Yale University Press, 2005, pp. 177-189. This is the catalogue of an exhibition of the work of Fra Angelico held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, October 26, 2005 - January 29, 2006.

2. Hood, William, "Saint Dominic's Manners of Praying: Gestures in Fra Angelico's Cell Frescoes at S. Marco", Art Bulletin, Volume LXVIII, Number 2, June 1986, pp. 195-206. See also the review of Hood's subsequent book on the paintings in San Marco by Anthony Fisher, OP; "A New Interpretation of Fra Angelico", New Blackfriars, Vol. 75, No. 882, The Friars and the Renaissance (May 1994), pp. 255-265.

.jpg)