Jean Bandol and Others, The Queen of Sheba Questions King Solomon

From Grande Bible historiale by Guiard des Moulins

French (Paris), c. 1371-1372

The Hague, Meermano Museum

MS RMMW 10 B 23, fol. 163v

"The queen of

Sheba, having heard a report of Solomon’s fame, came to test him with

subtle questions.

She arrived in Jerusalem with a very numerous retinue, and with camels

bearing spices, a large amount of gold, and precious stones. She came to

Solomon and spoke to him about everything that she had on her mind.

|

| Jean Bandol and Others, The Queen of Sheba Questions King Solomon From Grande Bible historiale by Guiard des Moulins French (Paris), c. 1371-1372 The Hague, Meermano Museum MS RMMW 10 B 23, fol. 163v |

She arrived in Jerusalem with a very numerous retinue, and with camels bearing spices, a large amount of gold, and precious stones. She came to Solomon and spoke to him about everything that she had on her mind.

King Solomon explained everything she asked about, and there was

nothing so obscure that the king could not explain it to her.

When the queen of Sheba witnessed Solomon’s great wisdom, the house he

had built, the

food at his table, the seating of his ministers, the attendance and dress of

his waiters, his servers, and the burnt offerings he offered in the house of

the LORD, it took her breath away.

“The report I heard in my country about your deeds and your wisdom is

true,” she told the king. “I did not believe the

report until I came and saw with my own eyes that not even the half had been

told me. Your wisdom and prosperity surpass the report I heard. Happy are your servants, happy these

ministers of yours, who stand before you always and listen to your wisdom.

Blessed be the LORD, your God, who has been

pleased to place you on the throne of Israel. In his enduring love for Israel,

the LORD has made you king to carry out judgment and justice.”

Then she gave the king

one hundred and twenty gold talents, a very large quantity of spices, and

precious stones. Never again did anyone bring such an abundance of spices as

the queen of Sheba gave to King Solomon. . .

King

Solomon gave the queen of Sheba everything she desired and asked for, besides

what King Solomon gave her from Solomon’s royal bounty. Then she returned with

her servants to her own country.”

1 Kings 10:1-10, 13 (Repeated up to verse 10 in 2 Chronicles

9:1-9)

There is also another reason for Sheba’s visit, according to the Bible. She “came to test him with subtle questions”.

The Questioning Queen

In fact her visit seems to imply that she is herself a woman of knowledge and deep thought, who questioned him, not so much to seek his answers but to test his knowledge and wisdom against her own. Out of this arises stories that support her own wisdom and demonstrate the depth of his. As one art historian put it “In the Orient, where legends, fables, and riddles abounded, and were in great favor, both with the Jews and with the Arabs, and where the solving of riddles was regarded as proof of great sagacity, numerous legends were woven around their names, and the subject of the riddles elaborately developed. The legends probably began as folkloric tales built on older myths of the Near East and went orally to and from the Syrian and Yemenite Jews, from them to the Arabs, and back to the Jews again, from people to people, and from country to country, often beginning with the words "it is told," so that their exact movements are hard to trace, though Babylonian and Persian roots for some of them are believed to exist.”1

The earliest images of the Queen of Sheba that I have been able to locate are the statues that are part of the decoration of the earliest Gothic cathedrals. Indeed, the first one comes from what was the very first Gothic building, the royal Abbey of Saint Denis, just outside Paris, built around 1140. Heavily damaged in the French Revolution, the head is held at the Musée de Cluny in Paris.

The second comes from the west façade of Chartres, built just before the fire of 1145 which required the rebuilding of the body of the cathedral that we still see today. In an eerie foreshadowing of the terrible fire of April 15, 2019 at Notre-Dame de Paris, only the recently completed façade of Chartres survived the fire of 1145. She stands with other Old Testament kings and judges: Samuel, David, Solomon.

At another door of Chartres, built approximately 50 years later, she stands again with Solomon and the Prophet Baalam. Her place is clearly among the wise.

|

| Head of Queen of Sheba from Abbey of Saint-Denis French, 1140 Paris, Musée de Cluny, Musée national du Moyen Age |

The second comes from the west façade of Chartres, built just before the fire of 1145 which required the rebuilding of the body of the cathedral that we still see today. In an eerie foreshadowing of the terrible fire of April 15, 2019 at Notre-Dame de Paris, only the recently completed façade of Chartres survived the fire of 1145. She stands with other Old Testament kings and judges: Samuel, David, Solomon.

|

| Jamb figures, Samuel, David, Sheba, Solomon French, c. 1145 Chartres, Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Chartres |

At another door of Chartres, built approximately 50 years later, she stands again with Solomon and the Prophet Baalam. Her place is clearly among the wise.

|

| Balaam, Sheba and Solomon, Left Jamb Figures, North Transept French, c. 1204-1210 Chartres, Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Chartres |

In Biblical illustrations in books and on decorative objects she is often shown in conversation with King Solomon. Frequently, their hand gestures indicate that they are having a heated discussion about some subject.

|

| Possibly Nicholas of Verdun, Gold Buckle with Solomon & Sheba Mosan, c. 1200 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Cloisters Collection |

|

| Solomon and the Queen of Sheba in Discussion French, c. 1220-1240 Amiens, Cathedral, Western Exterior |

|

| Solomon and Sheba in Discussions From Bible historale by Guiard des Moulins French (Paris), c. 1400 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 10, fol. 318r |

|

| Solomon Trying to Convince Sheba of a Point of Discussion From Bible historiale by Guiard des Moulins French (Paris), c. 1400 Paris, Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Francais 9, fol. 159v |

Some images make direct reference to puzzles that Sheba is reputed to have set before Solomon to test his wisdom and discernment.

One such is the subject of a tapestry woven in the Alsace region at the end of the fifteenth century. It represents a test set by Sheba in two forms, both of which require Solomon to make a judgment. Two children, dressed identically, stand between them. One is a boy and one is a girl. Sheba asks Solomon to say which is which. He determines, rightly, that girls are more likely to remove nuts from the ground by kneeling and collecting them in the folds of their skirts, whereas boys are more likely to pick up a nut to throw it at something. Sheba’s second question involves the two flowers she is shown holding. One is real and one is a very careful and realistic copy. Which is which? Solomon leaves the choice up to a bee, which can be seen (looking more like a small bird than a real bee) in the space between the edge of Solomon’s canopy and the scroll with writing on it at the center of the picture). Not surprisingly, the artificial flower doesn’t fool the bee and the real flower is revealed.2

One such is the subject of a tapestry woven in the Alsace region at the end of the fifteenth century. It represents a test set by Sheba in two forms, both of which require Solomon to make a judgment. Two children, dressed identically, stand between them. One is a boy and one is a girl. Sheba asks Solomon to say which is which. He determines, rightly, that girls are more likely to remove nuts from the ground by kneeling and collecting them in the folds of their skirts, whereas boys are more likely to pick up a nut to throw it at something. Sheba’s second question involves the two flowers she is shown holding. One is real and one is a very careful and realistic copy. Which is which? Solomon leaves the choice up to a bee, which can be seen (looking more like a small bird than a real bee) in the space between the edge of Solomon’s canopy and the scroll with writing on it at the center of the picture). Not surprisingly, the artificial flower doesn’t fool the bee and the real flower is revealed.2

|

| Poses Questions for Solomon Alsatian, c. 1490-1500 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Cloisters Collection |

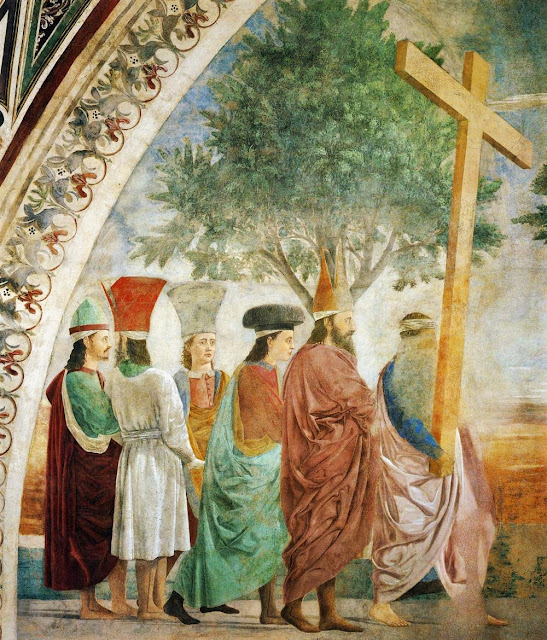

The True Wisdom of Sheba and the Holy Cross

One particular legendary aspect of the Queen of Sheba that reveals the great wisdom for which she was noted is that, alone of all people, she had the power to discern the wood of the True Cross hundreds of years before it was made into the Cross of Christ. The most famous depiction of this is found in the Chapel of the Holy Cross painted by Piero della Francesca at the Church of San Francesco at Arezzo.

“When Seth came again he found his father dead and planted this tree upon his grave, and it endured there unto the time of Solomon. And because he saw that it was fair, he did do hew it down and set it in his house named Saltus. And when the Queen of Sheba came to visit Solomon, she worshipped this tree, because she said the Saviour of all the world should be hanged thereon, by whom the realm of the Jews shall be defaced and cease. Solomon for this cause made it to be taken up and dolven deep in the ground.”3

“When Seth came again he found his father dead and planted this tree upon his grave, and it endured there unto the time of Solomon. And because he saw that it was fair, he did do hew it down and set it in his house named Saltus. And when the Queen of Sheba came to visit Solomon, she worshipped this tree, because she said the Saviour of all the world should be hanged thereon, by whom the realm of the Jews shall be defaced and cease. Solomon for this cause made it to be taken up and dolven deep in the ground.”3

Voragine doesn’t say in what manner Sheba “worshipped this tree” but clearly, he means that she showed some kind of deep reverence to it. It is difficult to determine how the beam is being used in Piero’s picture. It appears to be lying on the ground like a threshold as Sheba kneels in prayer before it. All the other versions of this part of the story that I have seen suggest that it is part of a bridge. Therefore, Sheba refuses to cross the stream using the bridge because that would be to walk on the wood of the cross. And, she therefore walks through the stream to reach Solomon who is waiting for her on the far bank.

|

| Giorgio Reverdino, The Queen of Sheba Bypasses the Bridge Made From the Wood That Will Become the True Cross French, c. 1530-1535 Chicago, Art Institute |

|

| Georg Pencz, The Queen of Sheba Avoiding the Bridge Made of the Wood That Will Become the True Cross German, c. 1532 Chicago, Art Institute |

Queen of Color

One further aspect of the iconography of Solomon and Sheba that should be noted is the question of color. Since both Solomon and the Queen of Saba (from Yemen) were desert dwellers one would expect that they would be of a darker complexion than someone from medieval France or Germany. Further, there is also a tradition of identifying the Queen of Sheba, whether from Yemen or Ethiopia, with the woman speaker in the Song of Songs, which was traditionally attributed to Solomon himself. There the woman clearly states: “I am black and beautiful, Daughters of Jerusalem — Like the tents of Qedar, like the curtains of Solomon. Do not stare at me because I am so black, because the sun has burned me.” (Song of Songs 1:5-6)

Although today it may be obvious that the queen from a portion of southern Arabia or from Ethiopia would be dark complexioned, there is very little evidence for a darker skinned queen in the art of Western Europe. This is likely due to scarcity of visual models for darker skinned peoples rather than to assumptions of prejudice. Western Europe today is far more integrated than it was previously, due to better communications and large scale immigration in very recent decades. However, even as recently as 40 years ago it was a novelty to see a dark skinned person in many parts of Europe. I know this from experience because, as a young woman I spent considerable time in the British Isles and in France. As a lifelong resident of New York City I was accustomed to seeing people of all skin tones in large enough numbers to be completely unremarkable. However, while France was somewhat more integrated than the British Isles, both large portions of England and virtually all of Ireland were completely white in tone. Travel then, while not as universal as it is today, was still considerably easier than it had been for all the millennia which preceded the twentieth century. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that in previous centuries opportunities for observing persons of color in Europe were seriously limited. However, there are a very small number of images in which artists, making the identification between the Queen of Sheba and the Queen of the South, who is also mentioned in the Bible, and the famous passage from the Songs of Songs cited above, did portray the queen as a woman of darker color, even of much darker color, than the king. But most likely they were drawing more on their imagination than on personal observation.4

|

| Nicholas of Verdun, Solomon Greets the Queen of Sheba Mosan, c. 1181 Klosterneuburg (AU), Abbey Church |

|

| Masters of Dirc van Delf, The Queen of Sheba Questioning King Solomon From Tafel van den Kersten Ghelove Dutch (Utrecht), c. 1400-1415 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M 691, fol. 148r |

Sexual Partners?

In the art of Western Europe there is little suggestion of sexual intrigue between the two until fairly late. Indeed, it isn’t until the nineteenth century, when wider travel and a romantic taste for the exotic became commonplace, that such overtones begin to appear, although they appear to have been circulating in Ethiopian, Jewish and Islamic folklore for some time.5

Solomon Led Astray

That there might have been some sexual contact between Solomon and Sheba is highly possible, given what the Bible says about Solomon’s harem. According to the Bible “He had as wives seven hundred princesses and three hundred concubines…” (1 Kings 11:3). So, he obviously had strong appetites. But it was this huge harem that was his undoing and the undoing of his legacy.

In his old age “…his wives had turned his heart to follow other gods, and his heart was not entirely with the LORD, his God, as the heart of David his father had been”. (1 Kings 11:4). Because of his change of heart God tells him that he will "…surely tear the kingdom away from you and give it to your servant. But I will not do this during your lifetime, for the sake of David your father; I will tear it away from your son’s hand. Nor will I tear away the whole kingdom. I will give your son one tribe for the sake of David my servant and for the sake of Jerusalem, which I have chosen.” (1 Kings 11:11-13) There are images which show this episode in his life and some of them identify the woman as the Queen of Sheba. However, the Bible does not imply this. The Biblical narrative suggests that the Queen had returned to Sheba many years before this occurs.

For more about the meeting between Solomon and Sheba see: "Solomon and Sheba, Part I, the Queen Comes to Visit"

For more about the meeting between Solomon and Sheba see: "Solomon and Sheba, Part I, the Queen Comes to Visit"

1. Ostoia, Vera K. Two Riddles of the Queen of Sheba, The Metropolitan Museum Journal, Volume 6, 1972, pp. 73-95. The text of the scrolls for their conversation reads: "Bescheyd mich kunig ob blumen und kind Glich an art oder unglich sind" ("Tell me, king, if flowers and children are like, or unlike in their kind"). To this Solomon replies: "Die bine ein guote blum nit spart das knuwen zoigt die wiplich art" ("The bee does not miss a real flower. Kneeling shows the female sex."), p. 75.

2. Ostoia, ibid.

3. The Golden Legend or Lives of the Saints. Compiled by Jacobus de Voragine, Archbishop of Genoa, 1275. First Edition Published 1470. Englished by William Caxton, First Edition 1483, Edited by F.S. Ellis, Temple Classics, 1900 (Reprinted 1922, 1931), Vol. III, page 78. Located at the Internet Medieval Source Book at https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/basis/goldenlegend/index.asp

4. Buschhausen, Helmut. The Klosterneuburg Altar of Nicholas of Verdun: Art, Theology and Politics, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. 37 (1974), pp. 1-32, see especially pp. 17-18.

5. Ostoia, ibid.

© M. Duffy, 2020

Scripture texts in this

work are taken from the New American Bible, revised edition © 2010, 1991, 1986,

1970 Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, Washington, D.C. and are used by

permission of the copyright owner. All Rights Reserved. No part of the New

American Bible may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from

the copyright owner.

.jpg)